This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

Overview of 1991

1991 was the year in which the parties, now past the sparring stage, began to flex their political muscle in earnest, honing their skills at counter attack, looking for points of vulnerability in their protagonists' positions. In 1990 they had taken stock of each other. Now they had to ready themselves for the negotiations ring.

The ANC took the lead. In its Annual Statement, 8 January, it called for an all-party conference on constitutional negotiations. The conference would have three tasks: to set out broad constitutional principles, determine the composition of the body that would draft the constitution, and establish an interim government to oversee the process of the transition. The government, Inkatha, and the Democratic Party welcomed the proposal; the CP, AZAPO & the PAC opposed it.

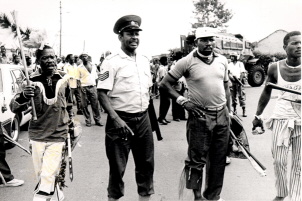

There was no diminution of violence.

Mandela and Buthelezi met twice to discuss the issue. They signed agreements committing their organizations to end the violence but neither agreement had much effect. Buthelezi used the first meeting to publicly catalogue his grievances with the ANC. He seemed more concerned with the perceived insults the ANC had heaped on him for over a decade than with the senseless violence being perpetrated in his and the ANC's name in KZN.

Meanwhile, the ANC became increasingly convinced that the government strategy was to outflank it among African voters by forging an electoral pact with the IFP. At the time the notion was by no means far fetched. The NP had opened membership to non-whites & even though there were no recruitment drives in the townships, De Klerk's popularity among the masses continued to hold up. They were still prepared to thank him for freeing Mandela, unbanning the liberation movements, and repealing the most repressive pieces of apartheid legislation. To many Africans he was still "Comrade de Klerk." Indeed, some opinion polls indicated that he might carry as much as 30 per cent of the African vote. Thus, De Klerk, the ANC believed, was not predisposed to ending the violence since the violence strengthened the government's hand & weakened the ANC's.

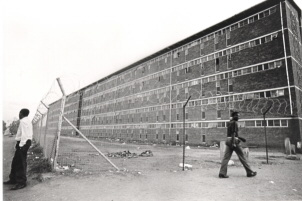

In March there was open warfare in Alexandra, South Africa's oldest township on the outskirts of Johannesburg. For three days, hostel workers supporting Inkatha and community residents supporting the ANC engaged in a battle that left 45 people dead. There were no arrests.

But despite the violence and the bitter war of words between the government and the ANC, the two parties met and brokered an agreement at the DF Malan Airport in Cape Town. This accord tightened the Pretoria Minute. The ANC would discontinue the infiltration of arms and personnel; cease to create new underground structures and membership of MK would no longer be unlawful. But the ANC still refused to agree to surrender its arms' caches or stop establishing Self Defence Units (SDUs). By the end of March 300 political prisoners had been released. Outdoor political rallies were legalized for the first time in 15 years.

Things appeared set for serious negotiations to get underway, but further obstacles arose -- all connected to the violence.

De Klerk announced that multi party negotiations could not be held in a climate of spiralling violence. The ANC, which held him responsible for not acting decisively to end the violence, was outraged. It responded with an ultimatum demanding that the government remove General Magnus Malan, Minister of Defence, and Adrian Vlok, Minister of Law & Order, who had become the visible public symbols to the ANC of clandestine, 'third force" activities being conducted by the security forces in collusion with Inkatha. It also made other specific security related demands, which the government had to meet before 9 May. Otherwise the ANC said that it would consider suspending all talks.

The standoff brought into sharp focus the government's attempt to control the process, to be at one & the same time the convenor of the process and a party to the process itself. The contradictions inherent in the two roles became the subject of acrimonious exchanges between government and the ANC. The government's action also infuriated Buthelezi who threatened to opt out of negotiations, the first of many threats to do so, raising on each occasion fears of civil war. Positions on process hardened as the government coveted ownership of the process. It responded in kind to the ANC, accusing it of trying to derail the process.

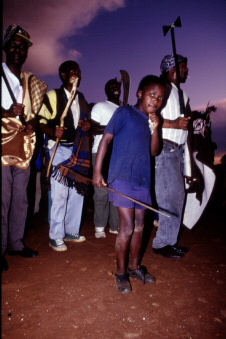

The war of words underscored the extent of the degree to which Buthelezi felt that the IFP were being marginalized. While the government dallied with the option of forming some kind of alliance with the IFP, the IFP wanted to create distance between itself & the government since the ANC continued to stigmatize it as a party that had been co-opted by the apartheid regime. Hence Buthelezi's threats were the only way other than violence he could carve out political space for himself outside KZN. The threats, however, often created their own backlash, unleashing the violence they condemned.

But it was also becoming clear that neither the ANC nor the IFP could rein in their supporters & much of the violence in KZN & on the Reef was beyond anyone's capacity to control. On the Vaal, SDU's were formed and operated outside of ANC structures; And in the hostels, Zulu, IFP supporting dwellers took matters into their own hands, seeing themselves as being embattled and isolated in areas adjacent to townships, which they perceived to be ANC supporting, and Xhosa. In the Vaal, ethnicity added to the tensions & misperceptions, which were grist for the mill of violence.

For a while during the heated exchanges that took place the prospects for a negotiated settlement became a little problematical. However, even at this point, one of the key features of the negotiations process pushed itself to the forefront: the commitment on the part of the government & the ANC to continue talking with each other despite setbacks, violence & what each regarded as gross provocations by the other.

In April the ANC published its constitutional principles. Its document called for a unitary, non racial South Africa, a democratic state with a Bill of Rights, an elected President as head of state, a prime minister who would head the cabinet, an independent judiciary with the powers to set aside laws that were unconstitutional, a two- house parliament composed of a national assembly and a senate, both elected by proportional representation.

Despite there being some significant differences between its proposals & the NP's there were sufficient similarities and points of common reference to provide the basis for negotiations.

With the ANC's deadline of 9 May looming, de Klerk, to avert a crisis, met with Mandela & Buthelezi. Although the three agreed that an all-party peace summit was necessary, De Klerk subsequently acted unilaterally. He called for a peace summit, without consulting the others, as if the process of restoring peace was something that he should take command of. And again, the ANC reacted angrily, announcing that it was pulling out of talks with the government and would oppose the government's peace summit. The government, the ANC insisted, could not be both player & referee. By calling the summit unilaterally it was trying to convey the impression that the government was not a party to the violence, but was willing to arbitrate the issue of violence among others. But this time it embarked on a mass protest -- two days of general strikes & consumer protests. The most compelling instrument in its negotiating arsenal was the power of the people. Bringing the economy to a halt cost business dearly. Business, the ANC hoped, would whisper in the government's ear.

The first major setback to de Klerk, however, came as a result of revelations that the government had funded Inkatha activities through secret accounts and provided arms to and training for Inkatha members. In addition, further evidence surfaced of the existence of security force hit squads. Although de Klerk insisted these activities had taken place before the unbanning of the ANC, the fallout forced him to relieve Vlok & Malan of their posts & the revelations put the government on the defensive.

Sensing the government's weakened position & that De Klerk's projected aura of being above all the dirty tricks of apartheid regimes, although he had played a senior role in the NP for many years, had shrunken in the Black community, the ANC pushed more forcibly for an all-party conference to discuss the creation of an interim government to oversee the transition. But the government, while accepting the need for some transitional mechanisms, still resisted the idea of an interim government.

With the two key players government & ANC in a standoff and Buthelezi making threatening noises that stoked the fires of violence, business stepped in. The Consultative Business Movement (CBM), an organization representing some business and church leaders launched the National Peace Initiative (NAI), which resulted in the National Peace Accord (NPA), the first multi-party agreement. A week later the government, the ANC and Inkatha announced they were ready to convene an all-party congress. The stage was set for "real negotiations."

What remained to be determined was which parties would be "eligible" to participate in negotiations & the method to determine the proportionality of representation i.e. in the absence of elections what gauge should be used to determine each party's insistence that it "spoke" for a majority of the disenfranchised?

In the run up to an all party congress, over 400 delegates representing 92 parties and organizations met in Durban in late October to launch a "Patriotic Front". These included not only parties that had held anti-apartheid positions but also some Black political parties that had collaborated with the apartheid government. The Patriotic Front endorsed an interim government, which would exercise, at the very least, control over the security forces and the electoral process. It also endorsed a key provision of Harare Declaration -- only a Constituent Assembly elected on the basis of one person one vote should draft and adopt a democratic constitution.

Subsequently, the ANC held separate bilaterals with most of the key parties and some of the marginal ones. Among the parties it met with were the PAC, AZAPO, the Democratic Party, homeland leaders, COSATU, the SACP, religious leaders and the NP. These consultations defined an agreed agenda for the all party conference that would address the pivotal questions relating to a formulation of general constitutional principles, creating a climate for a free & fair election, the parameters of the constitution-making body & an interim government, the future of the "Independent states", the role of the International community & time frames. On time frames there was the understanding that the process would have to be completed before September 1995 when the term of office of the NP government expired. Every party knew that an election without Black participation was out of the question.

The NP & the ANC agreed that participants should include all parties in the tricameral parliament, the parties in homelands governments and the independent states Transkei, Venda, Bophuthatswana & Ciskei (TBVC), the ANC, AZAPO, PAC, SACP, and the Indian Congresses.

The formation of the Patriotic Front altered the shape of the negotiations table insofar as the government was now facing a coalition of Black parties articulating a number of demands, foremost being the establishment of an interim government. Faced with the fact that it might have to relinquish power the NP mooted the idea of an "interim constitution" that ensured a government of national unity that would perhaps last for up to ten years. The Patriotic Front, on the other hand, wanted to draft the constitution within six months and for the interim government to last no more than 18 months.

Given a situation where some variant of an elected constituent assemble might draw up the constitution, the NP could not be certain that it would muster sufficient elected strength to safeguard its interests. It had to fashion a strategy, therefore, that would press for a) the broad constitutional principles agreed at the all-party congress to embody as much detail as possible, and b) these agreed constitutional to be immutable i.e. an elected constituent assembly would be unable to amend these principles. The ANC strategy would press for the obverse: for the agreed constitutional principles to be as limited as possible, leaving the meat & bones of constitution making to the elected body. In the end successful negotiations would depend on bridging the gap between these two positions.

The parties also agreed to adopt a decision-making process defined as one where in the absence of consensus the principle of sufficient consensus would apply. Sufficient consensus was defined loosely as there being enough consensus to enable the process to move forward.

Before the all-party conference, now formally called The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) met, Inkatha fired the first of many warning arrows across the process. It demanded separate places at the table for the KwaZulu government, Inkatha and the Zulu monarch, King Goodwill Zwelithini. When the monarchy was denied a seat, Buthelezi withdrew, although Inkatha continued to participate. Buthelezi had set his own demands. Unless they were accommodated he refused to attend CODESA. Of the major leaders whose parties participated in the process, Buthelezi alone did not attend either CODESA, or its successor CODESA II. Until the end he would remain a wildcard.

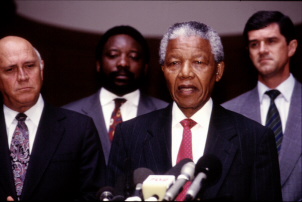

The first plenary session of CODESA took place on 20 and 21 December. On the opening day, Mandela verbally tongue- lashed De Klerk for not using the police resources of the state to bring a stop to the violence & insinuated police collusion. The event, which was carried live on SABC & radio stunned whites. Their president was being publicly dressed down by a Black man. If the encounter achieved nothing else, it jolted whites into a realization that in SA the days of Blacks prostrating themselves at the feet of the white leader were over. Here was a Black leader, articulate, confident & furiously cold in his anger.