This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

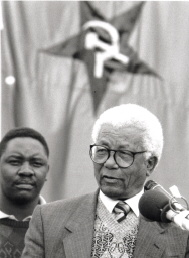

14 Jul 1992: Sisulu, Walter

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. I am talking with Mr. Walter Sisulu, Deputy President of the African National Congress on the 14th of July.

POM. I have so many questions to ask you, I hardly know where to start, but let me start at one rather obvious one. The bulk of your adult life was taken away from you, the more productive years of your life you spent in prison. When you came out of prison, when you looked at the South Africa you came into, what surprised you the most in terms of changes that had taken place and what surprised you the least?

WS. Well, that is a very difficult question, I have been asked this question several times. I have not been able to answer it satisfactorily because I looked around and I said, "What surprises me? Nothing." No change, the situation is the same. However, I found that the political consciousness of the people, and even kids, was on a very high level. That did surprise me, that in the light of the oppression intensified, they were not intimidated, but they were thoroughly organised and proud of being part of the struggle. I can't talk about the question of the attitude of the government because the attitude of the government was a response to the situation that had developed at that time. We initiated the talks for a peaceful transformation; Nelson Mandela, in jail, took the initiative. My personal attitude was that the move was a bit premature. He thought otherwise.

POM. He did this while PW Botha was still President?

WS. Yes. He was discussing with three officials, I think it was the Secretary of Justice, let me not give the names, but he was discussing with three officials, in fact I think even before he commenced this, because this was a slow process and he was separated from us. What I am trying to say is that the change that made the authorities, the regime as it were, to take a decision in releasing us, was in response to the situation that had developed. That did not surprise me very much, it was something that I had always been looking forward to, it was something we said in 1960 when we started uMkhonto weSizwe and we still remark, we hope that the whites in this country will realise that before it is too late, the necessity of talking about the country's political situation is great.

. So you will see from there that it is something we have been working on. In 1961, we organised a strike on the 29-31st May, when Verwoerd threatened to walk out of the Commonwealth and turn SA into a Republic. Mandela, who was underground, made a call for a new constitution in South Africa. In fact he wanted a constitution to be a constitution of the people of SA. He wrote to Verwoerd. What I am trying to say there is just that, we have been consistently demanding that this is the position.

. You will recall that the ANC's foundation was that we want a SA in which we all participate. So that right from the foundation of the ANC in fact one of the reasons of its foundation was the fact that we were treated as sub-humans.

POM. When you say that you were a bit sceptical about Mandela's initial overtures, were you sceptical in the sense that the whites were not ready, that the state still wanted to hold on to all of this power?

WS. Yes, that they would not easily respond to this request. Well, I was proved wrong.

POM. When de Klerk succeeded PW Botha, what was your initial assessment of him? Did you see him as a hardliner or somebody who would move the country in the direction of change, or somebody who would be more in the reactionary mould?

WS. No, I did feel that he was a member of the NP and the policy and outlook was the same. But I did feel that then he was more progressive.

POM. You were saying you saw de Klerk as more of a progressive person?

WS. Certainly more progressive than Botha.

POM. In certain respects that does not mean much, if you look at Botha.

WS. Yes, but I was looking at de Klerk as a man who had seen the world and I was looking at Botha as a man who was completely hopeless, who was fading away and I knew that he represented the most conservative element, although he was not in the Conservative Party, but he belonged to that school of thought, and therefore, I saw in de Klerk a man who had some possibility for some change.

POM. Were you able to, from the time you were released until Mandela was released, you were like the, de facto on the ground, most senior member of the party who had been released, did you have an opportunity during that time to meet with de Klerk yourself?

WS. No, my first meeting with de Klerk was when we met at Groote Schuur. The first official meeting between the government and the ANC, which I always characterise as a meeting, knowing the history of the country, there was nonetheless the hope that something may come out of it. I was impressed during the first meeting. We were meeting the Afrikaners whose policies were most brutal and whom we regarded as people who do not look at us as human beings in the true sense of the word. But here we were meeting, and I thought the meeting was a very good meeting. The statements made by both Mr. Mandela and de Klerk was that the aim is not that a particular party should be claiming 'we have done it' but the people of SA should feel that it has happened, we want the people of SA to claim the victory when it happens. That was a good approach. I was meeting him for the first time there and he did give a good impression to me. I had also admired him when Botha tried to undermine him, when he mobilised strong opposition against Botha and was successful against Botha in the manoeuvres that were taking place at the time.

POM. How has your assessment of him over the last two and a half years changed? I want to put that into a political and a personal context. In February 1990, I remember the first year we interviewed people both within your organisation and in the government, and most put a great deal on the personal chemistry, as they called it, that existed between Mr. Mandela and Mr. de Klerk and that personal chemistry and emerging trust would be a key element in moving the process along and now we hear that less than a month ago Mr. Mandela suddenly had to say that he never put that much emphasis on the personal relationship between the two of them and he has moved recently to making far more pointed and directed remarks about Mr. de Klerk and his causability for the stalemate and for the murder of your people. It seems an awful way to have come in a period of two years.

WS. Yes, Mr. Mandela was genuine when he thought that Mr. de Klerk was a man of integrity, but he also made a very significant qualification. He said that it must be remembered however, that de Klerk is a member of the NP. That qualification meant that, whatever good qualities de Klerk had, he is a political leader who is still subject to the party's policies.

. Now, within this period, de Klerk has shown to be completely disappointing even to those people who thought he was a bright rising politician. His failure to deal with the question of violence was alarming, and it is for that reason that he has been characterised to be responsible for violence in the country, because, here was a state unable to do anything, continually protecting, or making statements that protect the security forces. And then he did not appear to be doing anything to investigate what the causes of violence are. We had initiated the talks and we would be the most concerned about anything that was going to undermine the new process.

. There are a number of things within this period that happened: massacres on a large scale were taking place, I went for the first time to see dead bodies of the 36, of some of the Sebokeng victims. Even when we discussed with the police, there was nothing we could get out of them, you could see that these were people who were traditionally hostile to the black people and especially the ANC. When we were there, they arrested Themba Khoza and others. They said they found arms in their possession. My own belief is that they arrested them because we knew the information that those people were there.

. A year after that, they were released, Khoza was released, the reason that there was insufficient evidence against him. But look at the various large massacres that have taken place. One of the glaring issues was in Krugersdorp, the Swanieville raid by Inkatha. 28 people were killed. The police accompanied them to their hostels, a month later, three or five people were arrested and released. Now you get this type of thing, two or three people being arrested. No arrests have really ever taken place. Now, you know that situation would not happen in any other part of the world.

POM. And Mr. Mandela brought this continually to the attention of de Klerk?

WS. Continually to his attention. He has had very deep discussion with de Klerk. At one time he asked him, are you really in control? What was leading him to that question was because he is not the man he imagined he was, he is not the type of a man who could be so inefficient, that he is unable to understand these things and is unable to do anything. What conclusion then would you come to? Obviously that he connives, he is part of it.

. At one stage, de Klerk himself, according to Mr. Mandela, did say, "I am not as powerful as you think I am, I am not as in control as you are", something to that effect. So, the question is, what is the position and the status of de Klerk? In our own image, he has lost completely, he has become just an ordinary Nationalist like all other Nationalists. We nonetheless, recognise that he is a bold man. He took a bold action, he has got ability because he maintained that following despite the far right effort, despite Botha saying things about him. We acknowledge that, but we also acknowledge the fact that this is an obvious situation in which no intelligent man can fail to see. You can't expect a man like de Klerk to rely solely on the fact that I have not brought evidence that could lead to the conviction of a man, and you don't deal with this situation like that, you don't deal legalistically, you deal with the general situation as it exists, that is the attitude.

POM. When you use the word 'conniving', do you mean conniving in an active sense or in a passive sense, meaning that he does nothing to stop the violence as distinct from the violence is serving a purpose for him and he allows it to continue?

WS. Both. The whole question of violence is a strategy that is acceptable to the NP. The Bantustan policy is deliberately intended to undermine the liberation movement, they have not moved an inch from there. They want the process of change to take place, but they want more than that, that it should take place on their own terms. That it should not go to the extent whereby they lose power, they must still continue with power.

POM. I want to ask you, it seems to me that from beginning, you had two sets, as it were, of conversations going on. That the NP and de Klerk have always talked about this process as a process about the sharing of power, and they view any mention of majority rule as totalitarian and undemocratic or whatever, whereas within the liberation movement, the conversation has been about the transfer of power. These two things now seem to have reached a point of collision, it must be determined which one of them is it about. Which one of them is it about in your view?

WS. Well they profess to believe in a change that will bring about democracy in SA. If they believe in democracy, a change that will bring about democracy in SA, there is only one meaning and that is majority rule. By majority we don't mean members of the ANC, we don't mean the blacks, we mean the people of SA, we mean the sovereignty of the people, that is how we understand democracy. We understand it as it is understood the world over. We don't expect a special type of democracy for SA, once you take that line of a special type of democracy, you are in fact remaining where you were, rule of the whites over the blacks. Those are the differences.

. You talk today about the deadlock, that deadlock is precisely that. It is not just a question of 65%, 75%, it is in actual fact, a refusal to allow the majority to decide the fate of the country.

POM. I must tell you that we have talked to a number of members of the ANC and the SACP since we arrived and the feedback we get from them was that the figures of 70%, a 70% threshold for a provision of the constitution and a 75% threshold for a provision in the Bill of Rights amounted to - they would not quite use the word 'sell-out' but they would come close to it by saying 'almost everything has been given away'.

POM. Was there a reaction on the ground from the grassroots about those particular concessions you made or the ANC being prepared to make those particular concessions to the government?

WS. There were criticisms, some even sharp, but I think the criticisms were completely exaggerated. Although we are in agreement on the question of the percentages, when you are negotiating, you are negotiating and examining the situation as you see it. They were not satisfied with the demand of 75%, they were not even satisfied with the question of moving 55%. The concession of 70% was a package deal.

POM. If the government had in fact said 'deal done', would you have had trouble selling it to elements of your membership?

WS. It would have been a debatable matter. I must say that we have a difficult situation here. Violence is a destabiliser and is going on and in the light of this situation, you find violence is going on and then you find some concessions which are examined by others to be a little bit too far, yet we do have a remarkable unity. If you examine organisations in many parts of the world, we have got remarkable unity. We have got the Communist Party there, we have got the ANC and the trade unions. Fundamentally we pull together. There will be differences of emphasis on a particular issue. The youth follows even when we had taken a line which they did not like, that of suspending the armed struggle. Although we thought this would be the wise thing to do, it would hurt, but we had to convince the youth that this is the correct procedure. When they accepted it, they were now piloting it. Then they had two conferences, very well attended conferences endorsing it. That is why I say the unity you find is remarkable, unity of a leadership in spite of certain differences.

POM. You are now at a point where a similar [... did the government ...] let me maybe put it this way, I think you are telling me that the negotiators were willing to make a concession of 70% and 75% because the primary purpose in their minds was to reach a conclusion speedily and then deal with getting the interim government put into place, which meant that they would be in a better position to get their hands on the security or part of the security apparatus and try to bring the violence under control. The speed was seen as a necessary means of bringing violence under control and bringing violence under control was the primary objective at that point. Am I reading you correctly?

WS. Yes. The change when we made a positive demand for an interim government was a decision of the NEC, after the regions had discussed the issue. That the only way to end violence here is a speedy process of the interim government, that is the only way in which we think we can end this violence. As long as the security forces of the government are there, they are not likely to end the violence, so this was a deliberate strategy, this was an aim, a speedy solution.

WS. But a speedy solution, not moving away from the fundamental principles of majority rule, and I think our people as they are negotiating, they are aware of this and, as I say, that decision to say we will go up to 70% was also part of the package.

POM. Do you think the government blew the best deal they would ever have gotten by not accepting the package?

WS. Yes, I think so, I think that they left a chance where they could have gained. Whether we could have convinced our followers now, on the 70% is a debatable matter.

POM. What do you think led the government to turn it down? How do you read their strategy?

WS. The government was being consistent because anything on the question of minority, removing what they believe is their bottom line, they have to be very cautious about. To them this 70% was not enough, they believed it would not work, it would undermine them, that is why they turned it down.

POM. But where does that leave them now? How do you see them analysing their options and re-developing a negotiating strategy, there may be offers that they would accept for 70%?

WS. And they are accepting it now.

POM. Yes and they turned it down.

WS. It is no longer really a solution.

POM. What kind of options do you think are now open to them?

WS. The options must be examined on the basis of the demands put forward by the ANC to the regime. Commitment to the majority rule.

POM. Would you look for an express language that requires them to move away from this nebulous sharing of power to a straightforward commitment to majority rule?

WS. Yes. That is what we want. The government can also show its commitment also in other ways; the question of violence. We have given simple demands about the ending of violence. In order to negotiate the constitution properly, they must come along with these issues. As long as there is a question of violence, there is going to be no stability and we are concerned about that. That is why we want the international community to take part and to be able to say these are the factors, this is the situation, this is how we examine it, as in independent people.

POM. So you would be saying that one of your pre-conditions to a resumption of negotiations are clear cut mechanisms involving some international components that would be put in place to monitor the violence, and clear cut measures by the de Klerk government that are not only aimed at bringing the violence under control but are seen to bring it under control. You would be looking for results. The National Peace Accord was a beautiful Accord but it did not result in the reduction of violence, despite all the structures.

WS. And it was a slow process, even in exposing the elements which are involved in violence.

POM. So you would look for speedy measures to have an immediate impact and action. I suppose hostels would be pretty high up on this agenda.

WS. That is right. I must make it clear, we are in a hurry for the interim government, that is what we are in a hurry for. We think that there is a chance there. We will work various parties there with which we don't agree. CODESA I has shown they could work together, they develop a confidence in each other. Here the question of national unity, government of a national unity, brings together and creates a condition whereby trust will develop. I wish they could think along those lines.

POM. The expectations - when we came here two years ago and talked to people in the townships, the level of expectations regarding what would be available in a new SA were immensely high. People thought housing, electricity, water, education and all of these things would be changed in a very short period of time. (1) Have you seen a lowering of those expectations to a more realistic level in the last two years and (2) what do you think the people have a right to expect from a new government within, say, five years?

WS. Well, as far as the expectations of the people are concerned, the people expect that the question of housing, I wouldn't say is solved completely, but they would expect that a new situation would develop there, the housing, that the question of squatters would be solved and that the question of education would be dealt with. I am saying education will be put on a realistic level, in other words, the children will go to school, scholarships will be provided for, not for everyone, but something will be done to ease the situation. Water, electricity, yes. Those at least are the issues which top the list of expectations of the people.

POM. What about the youth in all of this? They seem like the wildcard. A whole generation of young people who were raised on militancy and mass mobilisation and knowing only a culture of militancy for two generations, who are now being asked to be tolerant to be restrained to take on responsibility, yet you have this huge unemployment situation which is not likely to change. I mean I have seen no projection that the unemployment situation will change anywhere in the short while. Are they are wildcard still instead of possibly being a destabilising influence in the township itself? Change does not appear to happen quickly enough, they see no change in their lives?

WS. Well, signs are beginning to show how difficult the situation is for people who have been brought up in the culture of the liberation, and they look upon the white rulers, particularly the hostility against the police, they find it difficult to be moderate in these issues. Yet, we are still able to move with the youth. How long? The longer the situation delays, the more it is going to be impossible to control that side.

POM. So it is just one more reason for a speedy resolution to this whole process.

WS. In the interests of everybody, including those who are in power now. The only solution is to move speedily, then we will be able to control and manage the situation.

POM. A number of people have suggested to us that if you look at the collapse of CODESA and its aftermath, that one of the political winners is the PAC as all along they said, CODESA is the wrong negotiating forum.

WS. They are completely wrong there. There is nothing that the PAC wins there. The reason why the PAC condemns CODESA, the main reason why they walked out, they said the negotiations were not opposed to, not even AZAPO, they were all not opposed to negotiations, but they want a construction of negotiations on their own terms, nothing changes fundamentally. They wanted negotiations to be abroad, not in SA. We had discussions with them that that is not realistic. The people are here, you are here, the regime is here. We are not in the same position as Zimbabwe. There is no reason why that should be the case. The fact that this has deadlocked does not in any way prove them right, there is nothing to make them right. They want negotiations, but they have got problems about that. So we agreed all of us, everybody agrees there should be negotiations.

WS. We are deadlocked on a question of fundamental principles. They want majority rule, we want majority rule. So what is their benefit here? What proves them right? Nothing.

POM. Again going back to the townships, the interesting thing is that we noticed in our first couple of visits that up until this year there was an extraordinary amount of goodwill among blacks towards de Klerk and we talked to supporters of the ANC who would refer to de Klerk as Comrade de Klerk. Is that now over? Is the goodwill for him, whatever existed, now evaporated? I have noticed the Economist ran a piece this week saying there was a campaign underway to kind of demonise de Klerk, that the ANC were associating de Klerk more personally with the violence and holding him more directly responsible, so they wanted to pull down his image among the black community.

WS. No, I think the question is really a fact of putting an issue correct. De Klerk has become swollen headed because the international community made a whole change in the de Klerk affair. De Klerk won the referendum. We were opposed to a racial referendum, but we were mindful that we want the process to go on, we did not boycott it, although we were opposed to it in principle. What did he do when he won the referendum? Instead of taking an advantage of something which happened for the first time in the history of this country, that the majority of whites said they are for negotiations, he took a tough line immediately thereafter.

POM. What was his strategic purpose here?

WS. It is an incorrect strategy, but he wanted to show how powerful he has become, that therefore the country can look to him, never mind the ANC. He made that mistake, that he underestimated the influence and the power of the ANC still. We would have used that situation better to find accommodation to work with the ANC in a better way.

POM. Let me ask you this question, I hope I can phrase it in the right way, but during that referendum, every report you will see in the United States, mostly the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Standard, the BBC or the National Public Radio, all the main television networks, they all refer to it as a referendum in which whites would be asked whether or not they were prepared to share political power with blacks. That is the way he talked about it in speeches that I have read. The ANC said nothing. They did not say, "Mr. De Klerk, that is not quite what this process is about, it is not about the sharing of power, it is about a movement to democracy, which means the majority rule." They said nothing. Mandela wooed whites to vote for the referendum. Do you think that, I am just adjusting this, that de Klerk might have thought that the ANC by the fact that it said nothing and went along with his interpretation of the process as he was presenting it to white people might have fallen into his interpretation a little?

WS. Well, in the first place, I think - I can't now remember. I think the question was, 'Are you for negotiations?' This was the issue, the question of, 'Are you for the sharing of power?' was not really the issue but it was, 'Are you for negotiations, the continuation of negotiations?' that was the issue. The whites had to say yes. Now I say de Klerk read wrongly that thing. He regarded it as a tough personal triumph and that he was in a position now to deal with the ANC as he likes. That was a wrong reading of the situation.

POM. Do you think some of that swelled-headedness that de Klerk may have developed, may have been further increased the invitation to go to, for example, to the Kremlin, to go to Moscow before Mr. Mandela, which would seem a kind of a slap in the face considering the close and long association between the ANC and Moscow, between his reception in Nigeria, with President Moi coming here, that international forces kind of conspired in a way to build him up into the state person, the person who was putting it all together?

WS. Yes, that is what I have said. The international community made him swollen headed, because they credited him with all these changes, and the question of going to these various countries like Moscow and even Nigeria, we did not oppose it because we have got a new situation. If we had opposed it, he would not have gone there. It is a mistaken idea to credit things to de Klerk, things must be credited to the forces that are engaged in negotiations. This has made him go wrong and I think that he was carried away by his ambitions, he cannot do it alone. He was beginning to entertain those ideas.

POM. So when you look to the future, you look to what you hope will be a speedy election. The question which arises is, is the ANC ready for an election in the near future? I will phrase that in a general way by using general statistics that we have come across by talking to people in the last several months who have said that, for example, if it weren't for black voters lacking any documentation at all, they wouldn't even be able to prove they are over 18% and that no real improvement has been made in that situation in the last several months, having identity documents or the lack off. And that there are a series of other either organisational or other impediments that might result in a relatively poor turnout in the African community in particular.

POM. Are you pleased with the progress made in this regard?

WS. I am certainly not pleased. I think that is a serious problem. We have to address it properly. It does exist, there are serious weaknesses there. Taking into account the fact that we don't know anything about elections, the NP and others have been at it for decades, it is a weakness on our part. But it is not such a weakness that alarms us. It is a weakness which we think is serious, must be taken into consideration and if it is not put right, it can destabilise us further.

POM. The final question, and thank you for being so generous with your time, this is a question that I spent a lot of time asking people, from the far left to the far right and everybody in between and in concerns the question of ethnicity. Let me just summarise how I have heard the argument being presented.

WS. Well, you are Irish, by the way?

POM. Yes, I know all about it. I am asking because my field of expertise is Northern Island, so it is an issue that as I have seen it move from Northern Island across Europe and now into the Soviet Union, and seen the various forms and manifestations that it takes, sometimes it is hard to detect, even though it is there. Let me premise the question by saying what I have heard from the ANC at almost every level is there is no element of an ethnic conflict involved in the violence here. What ethnic differences exist were the creation of apartheid. In other words ethnic differences did not precede apartheid, they preceded it to a point but they did not result in conflict. Among what I would call 'liberal whites', well thought of academicians, people who have studied this area, they would say, yes there is an ethnic dimension to the conflict but it is not the politically correct thing to say. If you went around saying, "I think there could be an element of ethnicity here", you would be accused of being an apologist for the government, or somehow supporting the government as regarding apartheid.

. If you look at the complex way in which ethnicity has expressed itself in the last several years in Europe and in other places, is there any kind of thinking going on that perhaps there is government involvement or security involvement, but that there may also be an ethnic component that must be addressed and that if not addressed, could pose problems in the longer term?

WS. No, I don't think so. There will always remain a problem. Perhaps I should put it differently, no, I think it is correct to say the question of ethnicity has been allowed to develop over the centuries by the ruling class. We will always have some affected minds, but that is not the real issue.

. The real issue will be bringing about unity between black and white, especially Afrikaner folk in SA. But you can get, from those Afrikaners who have been brought into the movement, it is unbelievable, you talk to them at any time, you can choose to talk to those who have been brought into the movement, it is a new world. I am not denying the fact that you have seen these divisions in the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, but you must also know how those were brought about. What I am trying to say is that it is not really the issue. The academics will say, "No, it is not really the right thing to say". In fact they are saying the liberal whites, the press, side with the government on the question that there is the ethnicity issue here. We say there is none.

. Buthelezi is brought up in the politics of the ANC too. Those politics are the politics of the ANC, he was a great admirer of Chief Luthuli, but it suits him now, because he is now wanting a partnership with the government, to utilise it as Zulu versus Xhosa. But if you look at the situation, the people in Natal, that is his area, the conflict cannot be Zulu/Xhosa. The conflict is the community versus Inkatha. So that even in that situation, it is not a question of ethnicity and yet the press/media has that as an issue.

POM. We have been out and talked to hostel dwellers in Thokoza, in particular we have spent quite an large amount of time there just talking to them about what they think is going on. It is extraordinary the manner in which they always talk about the Xhosa speaking people, the ANC as a Xhosa organisation that is out to dominate and destroy the Zulu nation, and they do it with extraordinary passion, and extraordinary conviction. What would you say to those people, how would you convince them that their perceptions are erroneous, that this is not what the process is about, this is not what the ANC is about?

WS. You see, for instance, one of the issues in CODESA is that the situation must be normalised. There must be no intimidation, the people must go to Zululand and recruit there for the ANC. That is the issue even today, but Buthelezi is opposed to it. Yet I have given you an example that in fact that he is opposed to that. In spite of the fighting we are talking about in Natal we have a very large following there. When Nelson came out of jail, he addressed a rally of about 100,000 in that province. Those were largely Zulus.

POM. My time is up and thank you very much for being so generous with your time. In the next couple of months, when I get back to Boston, I will have a transcript done and then sent back to you. Don't worry about the syntax, just look for whether it correctly states what you are saying.