This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

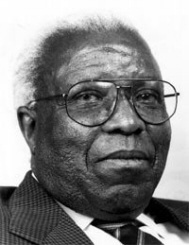

11 Jan 1993: Mhlaba, Raymond

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Let me start with something that's happened in the last couple of months and then work backwards. A question I am sure I asked you, it's in the transcript of the interviews (you have received the transcripts of the interviews, right?), a question I've asked everybody has been whether this is a process about the transfer of power which the ANC would say it was or about the sharing of power which is what the National Party has said all along? Then in October you had Joe Slovo's paper in The African Communist, the draft of a strategic perspective put before the NEC, resulting on 18th November with the National Working Group adopting a document called A Strategic Perspective which essentially says that power sharing may be necessary to attain our long-run objectives. That struck me as kind of strange that the movement which has had as its mortal enemy, the racist white regime, in some way it's trying to co-opt that regime. It's almost doing the opposite of what the National Party was trying to do in the eighties with the UDF or whatever. It's a different form of co-option. [I'd like to know whether ... one is at one place] and then go back to last June or May when the CODESA talks deadlocked over the question of percentages when the ANC had offered 70% veto threshold for the inclusion of items in a constitution and the government had turned it down but there was a lot of anger, as I understand, from talking to people at the grassroots level and among activists that too much was being given away by offering the government 70% in the first place and there hadn't been sufficient consultation. It looks to me over here that with this strategic document there doesn't seem to have been a lot of consultation with the grassroots. Where does policy presently stand on this question of transfer of power versus sharing of power?

RM. In the first place some people fail to appreciate how the ANC, for instance, operates. We have our own organisation and structure and it is through that structure that what the communists used to call in the olden days as democratic centralism where from the top to the bottom there's that communication from bottom upwards in consulting in a number of issues, discussing those issues, exchanging views. Now the truth of the matter is that we have a National Executive working in between the National Congress and it is the highest organ in national congressmen, conferences. Now we take decisions, we consult with branches, the regions and so on. Now the truth of the matter is that it may well be individuals are not quite happy on a certain decision by the National Executive but it does not mean that there was no consultation. There was consultation. In fact if you are up to date with reading newspapers you will find that at the funeral of Helen Joseph Mrs Mandela expressed herself and her husband explained to the public. Now that is the sort of ... perhaps you have picked up. Now we are democratic, the ANC is democratic, the Communist Party is trying to be democratic. We consult our organs, we work through our structures, we get mandates from time to time. The truth of the matter is that it is difficult to pooh-pooh the government, this present government. We have to work with this government. By working with the government I mean that in the first place we must acknowledge the fact that there is this government in existence and that this government has a certain following and that this government claims to be representing the whites. Of course we know that not all the whites are supporting the government. We would like if the ANC wins elections, we would like to see that certain parties are in fact represented in the government.

. If you call that power sharing we are saying that we should do that but one has to understand that we are not conveying the same meaning when we talk about power sharing. The government has got its own interpretation about power sharing, the ANC has got its own interpretation about power sharing. The ANC has always believed that we have to cater for the racial groups. For instance, there are the Coloureds, there are the Indians, there are the whites. We would like to see to it that organisations which claim to represent these racial groups, a certain percentage is represented in the government and that will be determined by the election results. We are going to go and run the elections. The Labour Party, that's Coloureds then the Coloureds have got so much. We should then see to it that one or two persons are in the government. The National Party, the Conservative Party and so on, those organisations which represent the Indians will go accordingly, in that ratio.

POM. Let me see if I'm getting you correct. Power sharing from the ANC's point of view would perhaps occur in a situation like the following ...?

RM. Let me put it this way. We have election results, the ANC is top, can run the government. The ANC says, all right let us consider those parties who put up candidates, their results, and we say the Nationalist Party should be - we think that we should have two people coming in and so on and so on. That's how in fact we envisage it.

POM. But it would be done voluntarily?

RM. Voluntarily. Not in terms of a constitutional - not in terms of any clause in the constitution.

POM. So there's nothing in the strategic perspective that would give the authority to ANC negotiators to negotiate a form of power sharing, maybe with sunset clauses or whatever, but that they would be written into the constitution for the next eight, ten years?

RM. Absolutely not. No, no. It should not be in the constitution but we should take cognisance of the fact that we have these racial groups. We should take cognisance of that fact. We have agreed on that, but it must not be a clause in the constitution which is binding us but we pledge that we will do so because it is the prerogative, if I may explain, of that party which has won the elections to take cognisance of the prevailing situation in the country, that we have whites who fear that we are going to dominate. We should bring them in by way of taking into account the results of the parties which claim to be representing the white community.

POM. Do you think there is still some misunderstanding out there as to whether power sharing should be written into the constitution?

RM. Well it is being debated, but I am just merely explaining the ANC's side. In all possibilities, because the ANC is democratic and so on, they would like to see that there is a peaceful commencement. In other words parties, the setting up of the government that is peace, that there's no resistance from certain quarters and we think that one way of doing so is to bring in, in terms of the vote, to bring in certain representatives of these groups into the government. But not by way that constitutionally you are forced to do so, no. But we pledge that we are going to do that. As I say, perhaps to conclude, as I say the matter is being discussed. You can see that there are groups that want to come in now. It is correct and proper for us to debate this with these people.

POM. So would a discussion of this take place in the Communist Party and will it reach a decision?

RM. You see the Communist Party is an independent party but it is in alliance with the ANC. The ANC and the Communist Party are also in alliance with COSATU. These are the three and, of course, I must say that you have the Patriotic Front now in the system which has made this whole thing bigger, or the Front larger. The tripartite alliance meets separately and discusses certain problems and there's a number of persons when they go to the Patriotic Front they have a certain stand, they have discussed it and decided on certain things, but they have to listen to the members of the Patriotic Front when they meet. They can't go blindly and say that we have decided it must be like that. What I'm trying to show is that the tripartite alliance is there, it operates. That is COSATU, the Communist Party and the ANC.

POM. What I'm asking is, could this document be adopted by the alliance and yet rejected by the Communist Party as an organisation?

RM. Well the Communist Party is in this tripartite alliance.

POM. So if the Communist Party had a special conference and it was discussed by the Central Committee and the Central Committee rejected a form of power sharing that the ANC was prepared to accept, what happens in a situation like that?

RM. Well it's a remote possibility I must say, but since it is a possibility I would say that it would be unfortunate. Relying on the past history, how we have worked over the years for such a long time, we haven't come to such a situation where there is such a major clash. You must know I am a member of the National Executive of the ANC. I have that privilege of discussing problems, but not only problems within the ANC circles. I belong to a branch of the ANC. I belong to a region of the ANC, right up to the top. I am also belonging to a branch of the Communist Party in the region and right up to the Central Committee. Now we discuss these things. I have personal friends in the ANC, Nelson Mandela, Sisulu, for years, from the forties. We discuss these things on a personal level. I can't imagine that we can at this stage come to blows which will mess up our own work for so many years. We will have to sit overnight and come to persuade. I have no doubt personally, with all the experience that I have and knowing these people, I don't think that there can be such a clash.

POM. Hypothetically if some power sharing arrangement were agreed upon and it was to be inserted into the constitution, would you have a problem?

RM. Well it has to be debated. Whether or not really in that way. The thing is, for instance, once you make an exception, one must say, "What about Zimbabwe", and so on. But the truth is that universally we go to elections, the party which wins the election has won the election, it has got the right to form the government. For practical reasons, governed by the prevailing situation in that particular country, we would say, well we think that this party should come in for the smooth running of the country, but it should not be a constitutional issue. If we are beaten in terms of numbers, the majority say that it must be in the constitution, it will be put in the constitution. But the prevailing view, which seems to be strong, in the ANC circles and in the party is that it shouldn't be.

POM. That it shouldn't be in the constitution. When one looks at what's happened to De Klerk since last March it seems as though he came out of the whites' only referendum on a high, with the mandate, with high popularity and it looked as though he couldn't have done a thing wrong. Every stroke he did received acclaim internationally. Since then he's just been rolling downhill. There have been resignations from his government, there have been scandals that have plagued his government. He was embarrassed by the failure of his own parliament to pass his Amnesty Bill and when he had to make revelations about firing or suspending the Generals the ANC's response was very low key and it kind of jumped all over him. My question is, do you get worried about the fragmentation of De Klerk's base of support so that as a negotiator he could become weakened to the point of not being able to deliver his constituency? In other words, do you need a strong De Klerk?

RM. Well we do need a strong De Klerk but we are also taking into account the present situation in South Africa that De Klerk can never have it easy when you talk about the historical situation of South Africa and the whites are living in fear. The whites have always been fearing the blacks. That we should acknowledge. I have been saying, for instance, even in the last weekend that the reason for this fear is based on the numbers of the blacks as compared with the numbers of the whites. When you talk about exercising voting rights they know that they can't compete with the blacks. The blacks will always win in terms of numbers. Now that is the fear of the whites and the whites think that having oppressed the black the black is going to pay back when it has got the power, political power, when it is exercising the political power it is going to say, "I'm going to fix you up!" We think we are not going to do that. They can't seem to accept our assurance. Of course a human being is a human being. I think that we have seen they have done so much harm that when the people have got power sharing they are going to fix you up. And we say, "No, we are honourable men. We will not think about wrongs. We will rather move forward as South Africans." This is what the ANC is preaching, supported by the Communist Party, supported by COSATU.

POM. Have you found since your release that that fear among whites is increasing as the prospect of an election and an interim government at least is becoming closer and closer?

RM. Well within the circles that I have moved, I have observed that the people are demanding an immediate installation of interim government.

POM. That's among the black people?

RM. We're talking about the whites.

POM. Whites, yes.

RM. And a certain section of the whites believe that the question of the economy will never be solved until there is an interim government. Of course these are the business people I'm talking about among whites. Now there is a very strong view among the business people, where I have addressed them, companies and so on, even in the economic development, certain business people to defending the ANC and so on, they think that it is only the interim government which can solve the question of the economy.

POM. There are sophisticated, educated white people one would expect ...

RM. From what I read about a certain section of the whites, the reactionary section, the Treurnicht and Terre'Blanche group, right wingers, now those they just don't want to see a government which they call 'Nelson Mandela's government' as they call it. They say, "Over my dead body". Those are the extreme reactionaries. They are still demanding their homeland, white man's homeland which we have been fighting over the years. They are still moving backwards. Now it is that group which is going to give us headaches even to the point of a counter revolution.

POM. Even to the point of a counter revolution?

RM. Yes, yes. Say now tomorrow you have an ANC government, everything in terms of rebelling against that government. There is also that possibility.

POM. Would you see support for that rebellion coming from members of the security forces?

RM. Police.

POM. Police who tend to be more conservative?

RM. But I can't go further than that because I haven't got the percentage of how much in the police force support the government, Treurnicht, how much in the army support Treurnicht, If you are demanding percentage on that I am not in a position to give it.

POM. What kind of a strategy would you suggest the ANC must have to deal with that possibility of a counter revolution?

RM. Well, the President has been asked to explain this, they say don't worry, several fellows still remain there. We know because the President knows that there are still reactionaries. There are elements which may actually bog down the government, the new government.

POM. Just on the question of civil servants, two things. In Namibia where they entrenched civil servants it doesn't appear to have worked out successfully. There still appear to be considerable elements within the civil service in Namibia that are anti-government and do more to damage the government than to help them.

RM. What I have received from Namibia is that the government are not having it easy.

POM. Not having it easy? There's only a nation of 1.5 million people. When you think of the vastness of South Africa and the vastness of the bureaucracy ...

RM. That's the point, that is the point. We can't really scientifically compare Namibia with South Africa. South Africa is highly industrialised. The percentage of whites and the percentage of the Coloureds and so on, now that's what we should take into account. That is why the President has gone out of his way to give an assurance that your jobs are not going to be interfered with by a new government.

POM. OK, but how do you at the same time build up, bring blacks into the civil service so that the civil service becomes more representative of the people as a whole? On the one hand you are going to have a government that is representative of the people and you're going to have a bureaucracy that's representative of the minority.

RM. This is our situation. This is the South African situation. Now what can we do? The whites deliberately deprived us of opportunity. In industry, skilled jobs and so on, nobody but the whites. If you were to ask me how many black engineers have you got in South Africa? None, almost none. How are we going to start? Don't ask me in the absence of all that how you are going to manage. That is our peculiar situation here in this country.

POM. Won't that pose you with enormous problems?

RM. That's is why I say that the possibility of the counter revolution is there. It's very high. In fact I wrote to the Secretary, to Cyril Ramaphosa on this, on the question of the counter revolution. Of course I was just giving him my personal view on a topic which was current then, in fact was sparked off by Joe Slovo.

POM. How would you see that taking place, the counter revolution? Under what circumstances?

RM. A counter revolution, of course, would mean that the reactionaries will put up resistance physically, not by word of mouth, would fight it openly in the streets. Now if you have that type of civil service then they will support that reactionary movement, plus the police, plus the army or perhaps a certain section of the army, a certain section of the police and perhaps a certain section of the civil service. Then we are in trouble. Now it means that it was the correct thing for the President to give that assurance to say that you still have your jobs. Whether they accepted that or not that's another question. But we are prepared to carry on. Then we will have to see what we will do if that counter revolution takes place. That comes then to the importance of De Klerk. In that situation he can play a very important progressive role when he says with his group that, "We accept the situation. Let us build our country. Let's go forward." He should get up there and say that.

POM. But that means you need him to be a strong political leader. You don't want to see his political standing being slowly eroded within his own community.

RM. Then I'm answering your question which you posed a minute or two ago.

POM. So you need a strong De Klerk.

RM. Yes I do.

POM. You may have to help him.

RM. Who wants somebody weak? We want a strong man, a man who can command.

POM. So in that sense you will try to help him minimise the difficulties he has in his own community?

RM. If it is in our interests, in the interests of the country we will do so, definitely, no doubt.

POM. When you look at the government what evolution do you see in their strategies since February 1990? Do you see them as having moved a considerable distance or do you still see them as playing the same game?

RM. You see the problem with this government, this thing Inkathagate, now this government still wants (that's why I said they have their own interpretation on power sharing) they still want to cling on to power. Now this government does not want really to be in government with the ANC. The ANC, in their way of judging the situation of the country, they think that the ANC is too left. In fact they openly say that it's dominated by communists. Now what they are doing is to organise what they regard as reactionary black organisations so that they should work with them and against the ANC. That's what they are trying to do.

RM. Now let me just conclude by saying that I wonder if the revelations are not a part of bearing my point out. I think they do, to show that this government actually is using a double agenda. Now I'm happy because these revelations are not our own making, they are just coming out, paying so much to Inkatha and so on, assigning certain forces to plan and plot against the ANC.

POM. Do you think that there are constraints on De Klerk with regard to his capacity to move against the security forces? That in a way he is hostage to the security forces? I mean they are in a way his last line of defence. If they abandon him he's got nothing behind him. Does he have enough power unilaterally to say, "I will clean up, fire left, right and centre", or are they powerful enough to ...?

RM. It's difficult for me to answer that question because I have to know in the first place how much is facing De Klerk, what his problem actually is in the army. If he knows such a percentage of the army is against him, such a percentage is actually supporting De Klerk, I am saying that there is a certain percentage but I think De Klerk knows better than myself. He knows that there is much, can give you specifically, he can be specific and say that so much percentage is actually supporting De Klerk, so much support is supporting him. And in that way he is in a better position knowing this, that if I were to do this, this is likely to happen against me. But he is still in power. He can make manoeuvres like, "I think General so-and so we can honourably discharge you with all your rights, get all your benefits and so forth." Whether or not that is really a joke is a big question because having given me all my benefits I say I'm not going to fix him up and go to your group and say that, "My services are disposed of, I'm no longer in the army but I've got the knowledge, the skills. Make use of my skills. I'm at your disposal."

POM. Would that feed into the counter revolution?

RM. In fact they organise the counter revolution.

POM. What about on the question of amnesty and the ANC? It seems to me their position is that they would consider an amnesty for people who have committed crimes while in the employ of the state provided that those crimes were listed and provided that the individual was named in much the same way as the ANC members were given indemnity when they listed their activities.

RM. And also at a certain stage when there is an interim government, when there is a government which is not only De Klerk on the picture, we too get the knowledge and decide on merit.

POM. In a parallel way what do you think the ANC has to do about the findings in its own report and then in Amnesty International of torture and abuses in some of the prison camps in Angola and Tanzania? Do you think it must name those individuals? Must it expel them from the organisation even?

RM. There's no doubt about that. The ANC has been frank and open. We haven't got the information, the report on the Commission. We are going to deal with those people. I've no doubt about that. We don't encourage irresponsibility. We can't encourage people who are torturing, killing other people within the organisation. That is not permitted at all. We are going to deal with them. How we are going to deal with them is another question, whether they are going to be expelled, suspended, that's another question, but action is definitely going to be taken against them. I know that. Whether a man was a Commander, whatever rank, he's going to be dealt with. That I am as sure of as right now I'm sitting here.

POM. Let me ask you about Buthelezi. Here he's come out with his own constitutional proposals with the implicit threat of secession. He's been sitting up there in Ulundi for the last six months making increasingly militant and threatening noises about how the Zulu nation will never accept an agreement to which they were not a party. Is he a bluffer or does he have the capacity to be a spoiler?

RM. A spoiler?

POM. A spoiler in the sense that if, say, the government and the ANC and even others reach an agreement and he does not accept it that he can continue to conduct a low level civil war in Natal for years to come.

RM. Like Renamo?

POM. Yes.

RM. That's what some people think. That's what some people think that at one stage the government was busy doing to prepare for another Renamo in South Africa and making use of the Zulus. How far the government has gone with that I don't know but at one stage we got that information. You see Buthelezi must be seen as a politician, a black politician who wants to make his own mark and his own country. At one stage he was friendly to the ANC. He is no longer friendly to the ANC. He is actually now completely competing politically on the political scene in South Africa. But I am not saying this because I am a member of the ANC. The ANC is strong, it is powerful, there's no doubt about that. The PAC is also trying it's best to emerge and to shine but it is eclipsed by the ANC. Now these organisations will stick out as far as they can, even AZAPO, for instance. I know, I've had meetings with AZAPO but to hear them talking they talk as if they have got thousands and thousands of them. Now if this is what even half a dozen saboteurs can do, they can cause a lot of trouble. Half a dozen I say, if organised, if determined they can cause a lot of havoc in the country. Those things we must take into account but the truth of the matter is that internationally and internally the ANC is respected.

POM. Granting that, what I am still getting at is that does Buthelezi have the power and the capacity to be a spoiler?

RM. What I'm trying to say is that here we have an ambitious man. If reactionaries can say "We're going to push you", that's how you should look at the ability and capacity that he may have. [Being used by this reactionary ...] The Zulus are a powerful nation, you can't allow this to happen and then train them and supply them weapons and so on. He can be a nuisance because he will side with the reactionary forces. That is why the Treurnicht group and the Terre'Blanche group support self-determination. Treurnicht wants self-determination, he's supporting Buthelezi. And I never thought Buthelezi will sit side by side with Treurnicht and say, "Our brother", and so on and so forth as is happening now. That is what is happening.

POM. Have you met Buthelezi?

RM. No, unfortunately not. He has been at Fort Hare but I as an individual have not met him.

POM. So you see him as somebody who must be accommodated in some way?

RM. We are going to accommodate all organisations. We are going to discuss with all organisations. But as I say that the determining factor, election results, that's the determining factor and we are not just talking loosely by saying here are the figures, ratios and so on, if you are insisting on the ratio and because you have got so much we think we will give you so much of representation. But it's not going to be written in the constitution.

POM. So if you were to go back to the question that I asked about the evolution of government strategy in the last three years you would essentially say that the government is still pursuing the same basic strategy of trying to mobilise other black organisations against the ANC?

RM. Yes, oh yes.

POM. And hope that the combination of those organisations, mostly Bantustans plus whatever support in the Coloured and Indian communities have, would be sufficient to offset the vote that the ANC might have.

RM. But although now we say this new parliament coming in, the Treurnicht group trying to work together with the Gqozos, the Buthelezis, the Mangopes, now that's a new element in the game. The government is still trying to pull Buthelezi's jacket and say, "Come this way, come this way my brother". How far that tug of war will go I don't know. But the truth of the matter is that all these groups I've mentioned they are fighting the ANC but the ANC is upright.

POM. What about APLA?

RM. APLA? APLA as you know is the military wing of the PAC.

POM. My point would be, and this appeared in an article in The Mercury over the weekend and it struck me as having some validity, and that is that the IRA has no more than maybe 100 activists that are out there at any given time. They plan their operations carefully, sometimes they are random, sometimes there are soft targets and sometimes there are hard targets but one way or another they manage to tie down 30,000 members of security forces and to create a social order where there are soldiers always on the street, where cars are searched.

RM. This is what I said just now, here. APLA are playing a determined game and can cause a lot of havoc.

POM. But that doesn't exist just on the right, that also exists on the left.

RM. Precisely.

POM. You could be undermined just as much by the right.

RM. I'm making a general statement which is true that such people can cause havoc. What I was trying to convey there, I was trying to say to you, we mustn't look at numbers, big numbers. Say, for instance, there is an operation here, the city hall of PE is brought down, we think that they are representing big numbers of people. I say that it may be just two persons doing that. It may be only two persons being trained by one person doing that. So if you take the logical conclusion, therefore, because the city hall falls down flat on the ground, then those people are representing thousands and thousands, you may be surprised how wrong you are.

POM. I'm saying the very opposite, that the IRA, for example, has the support of no more than maybe 20% of the nationalist community in Northern Ireland and 80% don't support them and in Ireland as a whole less than 5% might support them.

RM. Well I don't know about that. Let me tell you they seem to be powerful, they are doing havoc. I don't know, but you must take into account that perhaps it's a wrong analogy because you are dealing with people what they regard as a foreign element. I assume, the presumption I am making is that it's a national struggle. Do you see the point? A national struggle. Nationalism embracing the nation. I don't know the population there. We are not going to be governed under a foreign power. Now that is a different story, that's a different situation. The nation as a whole, that organisation is representing the nation fighting against a foreign power and in that case you can easily conclude they have the backing of the nation.

POM. Do you see multi-party negotiations getting under way in the near future?

RM. I think that's going to take place and we are working towards that direction.

POM. And when would you see an election by?

RM. Elections? We are hoping elections would be some time about the end of this year. Or the President is saying that he is even prepared to grant it earlier. Now there the element of democracy takes place and also saying that we are exchanging views with different parties. You can't just get up in the morning and say this is going to happen. But you are in a position to say, "I would like this to happen in this way". We would like to have elections this year, towards the end of this year. But if De Klerk and company say, "Let us have them in January 1994", I don't think we should put an obstacle as long as it's going to take place, the time is fixed, January 24th 1994, it's going to take place. I'm satisfied, I'm content and I will argue at the National Executive that that we must accept as a victory on our part. The principle thing is that we want the black man to exercise voting rights and those in power who have been depriving the blacks of their voting rights, they say, "You are going to get the voting rights, not tomorrow but next week." I will say if you are sure that thing is definite that it's next week it's a victory. I wouldn't really be fussed about it.

POM. Do you think that given the present levels of violence in the country that you could have free and fair elections?

RM. Yes I think, yes. But I don't think this violence is going to bog us down not to move in order to have electioneering campaigns. I move about, I've been making the rallies, I have mass demonstrations. Who's going to stop me when I'm now conducting an election? Nobody. When it started I move about, I go, I call back from here, from my car, with one security fellow. He's useless in terms of protecting me but we go, no problem. If we are going to fold our arms and say let us wait for violence to be over then we are wasting our time.

POM. Just one or two last questions. Government people that we've talked to insist that at CODESA 2 the ANC agreed that the boundaries of the regions would be drawn up in a forum other than an elected forum, i.e. it would be drawn up by CODESA, and that the powers of the regions would be entrenched in the constitution and that these powers would be agreed upon also at CODESA and not in an elected Constituent Assembly.

RM. No, I don't recall that. What I do know is that the ANC is saying that we have only a central government. The other structures, provincial, local authorities, should not in fact have power superseding the central government. That is fundamental. Whereas the government and even the Democratic Party would like the regional authority to have such powers which in fact they can easily say, "To hell with central government", sort of thing. Now we say you are actually introducing apartheid through the back door.

POM. So they want a weak central government and strong regional governments so that they can control sufficient areas where they can be in control?

RM. Exactly. We want a central government, an authority, and we would like these structures to operate but they are subject to the central authority. They have certain rights, certain authorities to exercise on those levels, regional, local government and so on but there shouldn't be any clause which says that we are independent here, we can decide even against decisions made by central government. Central government should be supreme.

POM. This is a question that's often asked in surveys or polls that are taken at least in the United States and I think they are used here too increasingly, and that is: Are you better off now than you were on the date that Nelson Mandela was released?

RM. You mean as an organisation?

POM. Yes, are you better off?

RM. In strength and otherwise we are better off, yes.

POM. You are better off?

RM. Better off.

POM. Are the South African people better off?

RM. No, they are not better off.

POM. I mean either blacks or whites, particularly blacks.

RM. You know, let me tell you something. As I move I see a lot of poor whites in a bad way. I am saying to my traveller, "Do you see that the poor whites are increasing numbers?" You go to the townships, look at how people live there, squatters. You know the squatters are multiplying. I go to the Transkei, Butterworth, it's just mushroomed. I say, "What is happening?" The Transkei, Butterworth. You ask me the question, are we better off? We are not better off at all. A number of people have been abroad who come, they say, same old story, which is an act. Bad location, no sewerage, no water. It's a bad situation, let me tell you. In fact the government has failed completely, completely. In other countries they are supposed to consult the voters, let me tell you, but the whites of course they are enjoying certain things. You don't see them marching the streets. They say, no, look at the townships and so on. They are comfortable.

POM. After, say, an ANC government takes over, after five years what should the average black person be reasonably able to expect from that government?

RM. Let me tell you, I have said it in some areas where I visit, that we mustn't expect miracles with the new government. 100% promises are going to be a bit hard. We use the language of imbalances, economic or what have you. If you want to balance those imbalances it's going to take years and unfortunately the expectations from our people 'because I'm black miracles will take place', is not going to happen overnight. But, I say if we go into power tomorrow we must declare that we are aiming at certain budgets for housing schemes, for this and that and that and that, but whatever happens, but at least declare that. And not just by word of mouth and trying to bamboozle the people. You must consider that in fact you are going to attempt to see to it that the budget is immediately put into operation to meet expectations. I don't see what makes the local authorities, the government not, there's land, start schemes of housing. Maybe even four-roomed and so on and starting to collect lists of people. You go to room number one and complete it and so on. That type of plan I talk about and I don't see if the government can't do that then I don't know. I really don't know.

POM. OK. Thanks once again. We'll be back again.

RM. Good. I hope when you are back I won't be sitting here.

PAT. You'll be out campaigning.

RM. Campaigning, yes.

POM. You'll be Minister for Finance.