This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

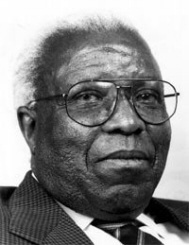

09 May 1995: Mhlaba, Raymond

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Premier, let me begin by asking you about the changes that have taken place in your life. Up till 1989 you had spent 27 years in jail, you were released, you take part in political activities and four years later you are Premier of one of the provinces of South Africa. One, did you ever expect this to happen in your lifetime?

RM. No, I didn't expect to be the Premier let me tell you, let me speak the truth. All I was looking forward to was that one day I may be in parliament or provincial government as an ordinary MP or in the local government at the City Council affairs.

POM. Did you have any doubt that during your lifetime apartheid would be ended or did you think that would be left to the next generation?

RM. No, I, we strongly believed, all of us, that within our lifetime, there is an expression 'freedom in our lifetime', we have been talking about that in our campaigns, freedom in our lifetime indicating then our strong belief that we expect that within our lifetime we will be free.

POM. Changes in our life, when you came out you lived with relatives, I don't know where, but you lived in a house and now you have an official residence, you are surrounded by all this paraphernalia of state, somebody opens the door for you every time you move.

RM. That is true, yes.

POM. How has it affected you in a personal kind of way in terms of your own values?

RM. Well some people say all is in the mind. It is true because when you are placed in a certain situation the mental adjustment has to take place but if you expect that, that it has to take place, you smoothly adjust accordingly. For instance, moving from a two roomed house to a three roomed house in Port Elizabeth in the township, from there when I was released I stayed in a flat with many more rooms, bathroom and all this, kitchen and all that, going upstairs, in Port Elizabeth. From there to the State House, as well as you say that there is security, there are people who work in the kitchen, not only one person, and there are people who move about security and they have got a motor car, have got drivers, not only one driver, and as you say somebody opens the door for me, I get into the car. It is something new to me. But I say, well, I have to accept the mental adjustment, that I have reached the stage, I am in this environment, let me just go into the environment and adapt myself to that environment.

POM. What have you found to be the hardest thing to adjust to?

RM. Well let me say that when we entered the State House it was too big for us and I felt lost, in fact there are certain rooms for months I didn't even know, and my wife was uncomfortable, lonely, away from friends, staying alone there. It is only now that she has got an office and she is doing to cater for the disabled people, to collect clothes and old clothes and so on. She is busy, she has got two persons working with her in the office. Now in the mornings she gets dressed, goes to office, she comes back after five and is getting used to the situation now.

POM. Just turning to the Eastern Cape, this province has particular challenges. Could you tell me what you see as being the greatest challenges facing you as Premier and what you hope to be able to do between now and 1999?

RM. Well let me say that we have gone over very important hurdles, the bringing together of the three administrations, that's a very big leap forward. We have managed to do that. We have got one administration now and we have one Director General for administration. We have managed to integrate the police force, Ciskeian, Transkeian, Cape Provincial Administration areas in the Eastern Cape. We have got one police force integrated with a Provincial Commissioner of Police and with his subordinates. Now having done that, having set up the legislature, having a government in place, we now want to move to come to stage number two I call it, the stage of delivery. One has, of course, to bear in mind that we have made promises during the election campaign period where we were saying that if you elect us we intend building houses, we intend introducing compulsory free education, we intend building up clinics, schools and so on, mending the roads and all that, and going to the rural areas and introducing electricity, water and so on. Now the period has come for us to do that in a visible form, that will be the period of delivery. This is the period we are entering. We have started in certain areas. For instance, the question of electrifying in Transkei, we have started in a small way of course and we are advancing to go to the rural areas. We are planning to mend roads and all that.

POM. Just this morning on the way out we were looking at the results of the Central Statistics Office survey in which the figures for the Eastern Cape are particularly disturbing. It has the highest rate of unemployment, it has the highest rate of non-electrification in rural areas, it has the highest rate of unemployment in rural areas. If you are dependent upon the central government for an allocation of funds from central budget how can you raise enough resources to deal with these multiple problems?

RM. Well one has to, if you want to exercise your mind freely and soberly, we must know that we are talking of a situation which is not of our making. It is a situation which we have found. It does exist of course. Let us admit that, but we intend changing the situation. Some of us have gone a long way in inviting foreign investors to invest in this province. I have been in Germany in February 1994, even before the election, canvassing to see that investors come and invest here. There is, of course, internationally a favourable response to our situation in South Africa. I am speaking now generally. The investors have come to the conclusion that South Africa as a whole is a place where you can invest, unlike before.

POM. But they haven't put their money here yet.

RM. That is true. The truth of the matter is when do they start? Also we have to organise the internal business people to expand, to build more factories and so on, even that from the point of view of asserting that there is good reason to do that, to invest and to expand. It does appear that the business people have accepted that. Now on our part as the government we have what is known as RDP. RDP is to balance the imbalances, the economic imbalances. Now what we intend doing, in fact we have taken a decision already, that we must build schools, we must build clinics, we must build hospitals, we must mend roads and also introduce water and electricity, all those processes must involve the people in the various areas where we work and in that we are also targeting the unemployment situation.

POM. When I picked up the paper today it said that the budget had allocated the sum of R2000 for the RDP, that's not going to build many roads.

RM. That is true. We are also looking at the allocation from the central government to help us.

POM. What I am getting at is, since you can't raise revenue of your own, in other words under the constitution no-one has tested it yet.

RM. But we can make use of levies as a province, but what should be understood that within the interim constitution the central government has to give us a certain allocation, certain allowances from the central government from the revenue which is derived from taxes imposed by the central government. A certain percentage should come to us, that is a provision within the constitution.

POM. When you prepare your budget do you base it on the basis of the amount that is allocated by the central government?

RM. No, no, no. We base our budget on our needs, on our needs, and you take into account the Ministry of Economic Affairs portfolio and so on, all the portfolios. You bring this together then you produce your budget on the basis of that.

POM. As far as I can see, every province so far is going to have a deficit, that they are not getting enough money from the central government to meet their needs. Now if you are faced with a situation where, one, the central government has said that it wants to cut the percentage of government expenditure from 21% of GDP to 17%, that it wants to rationalise the civil service and eliminate thousands of jobs, without raising taxes, how can you, again in a meaningful way, redress the imbalances that exist?

RM. Well the government has to consider that, the central government has to consider that, how to make that situation by way of raising taxes and so on.

POM. Would you yourself be in favour of states or provinces having the right to levy taxes like a sales tax or an income tax or whatever or do you think the question of taxation should be left exclusively to the central government?

RM. I think it should be left exclusively to the central government with the provisions that we can make certain levies. I think that so far we haven't gone beyond that.

POM. When you're talking about levies you're talking about things like a levy on ...?

RM. For instance on traffic and so on, traffic offences and all that.

POM. OK. Going back for a moment to the constitution, or going back even further, have you now amalgamated the civil administrations of the Transkei, the Ciskei and what used to be the Eastern Cape?

RM. We have, we have got one administration now.

POM. Now did this involve the laying off of many people?

RM. Not at all, not at all. You see in meeting the question of, because we have been saying that we want a lean administration, now we can meet that situation in the sense that according to the constitution we are not supposed to sack anybody, any civil servant and the province is big. If we intend building, as we intend doing, to build hospitals all you need to do is to shift certain nurses to go and accommodate, if at all there is a shortage of nurses you can employ new nurses or you can make use of existing nurses by shifting them to go to the various areas as you advance building the country. The same goes to the schools, goes to health and so on.

POM. So you had three sets of school teachers and you amalgamated them?

RM. Into the one yes.

POM. Civil servants in general I suppose, I don't quite get it, you say you've got the Ciskei here, you've got the Transkei there and you've got what used to be the Eastern Cape here, you rationalise the three but you fire nobody so you must have three people at the same level doing the same kind of job?

RM. No, no, no. That's the wrong approach. The people are there, the number is there, the total number of nurses, we are talking about nurses, they will still be there. The mere fact that the administration of Transkei is dropped, the administration of Ciskei is dropped, the administration of the Cape Provincial Administration is dropped, you say you are one province, it doesn't mean that the demand disappears, the services are there, the demand for services is still there. All you have done, you have centralised the command, if I may use that military language, but the number of people in the Transkei remain there, there are still that number. If then the hospitals which were there were serving the people in the Transkei we have not diminished anything, but you are improving the services. And it may be in that process of improving the situation then you may need even additional people. All you need is capital to run the country.

POM. Do you ever find it a bit strange that you as a long time communist now find yourself advocating the principles of the free market and talking about the need to attract foreign investment and the need to attract capital?

RM. Well let me tell you, since you are talking about being a communist, that Lenin in 1917 was talking like me in the Soviet Union. When Lenin spoke about the five-year plan he spoke about mixed economy, that is the communist Lenin. These things are not new by the way. When Lenin says, Let us copy from the capitalist, accept those good things and run our country, there's nothing wrong in that. Even capitalists are producing good management. I am not going to drop that good management because I am a communist, I will take it and make use of it even if there is a socialist government in this country.

POM. I remember when we came here first in 1989, 1990 and would meet with people in the UDF or the ANC or the SACP at that point and they would all talk about the need for nationalisation, talking about maybe nationalising the mines or nationalising key industries. Now we're seeing people talk about privatising, I find it amazing.

RM. Well you know what we are dealing with, it's not static, it's revolutionary changes, changing situation, changing of methods of dealing with the situation, that is in fact a revolutionary theory which we believe in.

POM. Just turning to the constitution, I think the National Party and the IFP, as I understand it, wanted to get as much of the constitution in place at Kempton Park before an election because they would wield more power at that point than they would after an election, and from what Cyril Ramaphosa has said, in the Constituent Assembly he talks about building a new constitution from scratch. Do you think the constitution that will emerge will be the interim constitution modified and refined to take care of certain imbalances or things that are out of kilter or do you think that it will produce a constitution that will really be drawn up from scratch putting the interim constitution aside, although this would have to follow the constitutional principles that are laid down?

RM. Well you see the interim constitution is there. Now I can't imagine just throwing it away in toto as it is. You have to examine the constitution and find out defects in the constitution and try to improve that to produce what we call a new constitution. Now being democratic we are inviting bodies, organisations, individuals to come forth. In fact we are making a campaign, we are going round to find out, as we used to do when we were compiling the Freedom Charter, to go around and say, What type of government do you like? Come to us, tell us, what type of a government would you like? Then they say, I would like this type of government', and so on, and you write it down and so on. You compile all these views and produce the Freedom Charter. That's what we are doing now. Cyril was here the other day. In fact last weekend. He has been to some rural areas, Peddie and so on, go to the people and find out what type of constitution do you want? Rural people, they state what they want - he must write it down. And he will go round and will sit down and say, Well this appears to be a general view, which is good. He must put it in the constitution. This is how we run our campaign today on the constitution.

POM. So on the one hand you have senior ANC personnel going around the country inviting input from people on what should be in the constitution. On the other hand it's very difficult to get people to register to vote for the election in November and if I recall I think the Transkei, or what was the Transkei, is having particular problems in terms of the number of people who have already registered. One, what do you think is the reason for the apathy on the part of the people in general and, two, why does the Transkei experience particular problems when it comes to voter registration?

RM. Well you see besides the fact that Transkei at one stage regarded itself as an independent country and some people actually felt that Transkei was in fact independent and that independence went on for a couple of years and now they think that the change for them to be part of a province is going to deprive them of a number of things. There is that resistance in their minds and in their behaviour and so on. But there is another element which we will have to examine, the element of the fact that when we started the general election last year, 27 April, we didn't go to the people and say register first; they find it strange now when there is a government, people's government, to talk about registering as a voter when in fact they did vote. We have to debate that, we have to show to them that there is a need now for you to register so that you are on the voters' roll, you are a voter and you are going to vote so that there is a municipal election where you are going to use your City Council members. Now we have to do that and some people say that this move, after we have our own President, he wants to step down from the present government, there are such questions. We have to debate that and to show that in fact the intention is that although we started by taking part in the elections last year, now there is time for you to register as a voter and then to be on the voters' roll and you must vote in this election.

POM. Do you believe that many people, particularly in the rural areas, have any real idea of what local government is?

RM. In the first place, by the way, you should know that those who talk about local government, the black people never took part in the local government in the past. They know nothing about it. They don't know the mechanics of running local government. Now you are telling them that you are now going to run the local government yourselves. They must now apply their minds as to precisely what they are going to do. The first thing that you say to them is, Register as a voter, thereafter there are going to be elections, you must elect your representatives or you yourself may be elected if you want to stand, and so on.

POM. Do you have government programmes under particular ministers whose function is to go out into rural areas in particular, but even urban areas, and teach people what local government is and what role they will play in it?

RM. Well we have got ministers who are dealing with local government. Here for instance in this province we have got Max Mamoxe who is the Minister of Housing and Local Government. In the nine provinces you have such a minister. It is the task therefore of that minister to go to the rural areas, to the urban areas, to educate the people about local government, but of course we can't just leave such a big task to this one ministry. We as a government, as a whole, must take part to see to it that we reach the rural areas and the urban areas.

POM. Are you satisfied that at this point things are going well or that a lot has to be done?

RM. I'm not satisfied, that is why I welcome very much the extension of time. Within this extension of time I believe that we will be able to reach all the areas in good time so that people are registered. That's why we must intensify this campaign now.

POM. What role do the traditional Chiefs or the Paramount Chiefs play in all of this?

RM. Fortunately enough, I must say, they now say they are prepared to take part and in fact we are making use of them now to touch the rural areas.

POM. That would be Contralesa?

RM. Through Contralesa, as individuals and so on, that they should take part, that they should cover their areas. If they need transport we will accommodate them, we will supply transport so that they should reach the various areas.

POM. Now would they more or less be in charge of registering people in their area?

RM. When you say be in charge, they are going to be instrumental in the sense that we deliver a number of application forms to them and say to them that they must distribute them in their areas. You make use of headmen and other agencies. This has taken place already and it is taking place.

POM. Now is it your intention to establish a House of Paramount Chiefs?

RM. In terms of the constitution we have to, there is the House of Traditional Leaders in the constitution. We are busy with that, we are discussing that with the traditional leaders but they have been unhappy about the number, we have to establish the question of the number now, I think even that we are going to compromise.

POM. They want more?

RM. They want more.

POM. Do they want also to be paid and have drivers and cars?

RM. They want to be paid. They want all those things.

POM. They want all the perks.

RM. Yes that's right, that's right.

POM. In Ireland they call it the Mercs (for the Mercedes).

RM. That's right. They want all that.

POM. Being a Chief is one of these hereditary things from which you just happen to be born to a certain family and you're a Chief and you get to exercise this kind of authority and in that sense there is nothing democratic about it at all. How do you find that with your belief in democracy and having gone to jail for democracy?

RM. After all a communist doesn't provide a monarchy and so on.

POM. Yes, you get the drift of where I'm going.

RM. You see there is a saying in English that you can't run faster than the horse you are riding. Where we are now in South Africa we have Chiefs. For me, being a communist just to pooh-pooh that they don't exist, it would be stupid of me. I will be running faster than the horse I am riding. I am riding a horse and this horse says, where we are there are Chiefs, these Chiefs have got certain political power in certain areas, they are running those areas. I must take that into account if I want to run this country. But if I am running faster than the horse I'm riding I will say, To hell with the Chiefs, and then there is trouble. I am not prepared to do that.

POM. Just looking at the interim constitution, now on a scale of one to ten where one would be very unsatisfactory and ten very satisfactory, where would you place the interim constitution? A three, a five, a seven, an eight, or whatever?

RM. You mean the interim constitution?

POM. Yes.

RM. I don't understand your question.

POM. You have the interim constitution and I say now here's a scale and number one at this end means that it's a very unsatisfactory constitution, number ten means it's a very satisfactory interim constitution, a five means it's average.

RM. No, no, I understand now, I'm sorry, I understand you now. I couldn't get the question at first. Well from the very beginning, by the way, once we said that it is an interim constitution we meant that it is going to serve for a very short period of time. In fact we said five years actually, to be specific. And we intended then that we are going to have a real constitution for South Africa. So when we talk of an interim whatever, that is a type of experiment which is going to serve for all times, let me put it that way, which meant therefore that there are defects in that interim constitution which we have to correct at a given time. Here we said five years time.

POM. What would you point out as being the major defects that are in need of remedy?

RM. In the interim constitution? For instance there is a fundamental point which must be taken into account by all democrats and that is that a constitution which will be popular, or should be popular, is the one which will give a provision that that party which wins the election would have the majority, must run the government. I mean this is a universal phenomenon. Why are we now being an exception in this country? We are doing so, we have reasons of course for doing so, of this interim phase, because of our peculiar situation in this country where the minority were running the country as against the majority and that for us to have mental adjustment of certain people and to create peace we should have an interim constitution. We must correct that by saying the majority party must run the country.

POM. In the last couple of months then there has been a lot of hullabaloo both in the media and in government circles and on the streets about the level of crime, about how in many areas the country is close to anarchy, where the murder rate here is the highest in the world by no matter what standard you use, there were 67,000 violent crimes last year. I think a violent crime was committed once every seven minutes and there was talk of crackdown and the army now has more troops deployed in policing than they had at the height of the Angolan war in Angola. One, do you think it a bad thing that the army should be given police functions?

RM. It's a bad thing, it must be stopped. In dealing with the total situation you can't just concentrate on a specific issue, you must deal with the totality if you want to make a good analysis. Now in our situation one has to take into account that the question of the unemployment is not the product of this government, it's the product of the previous government which means then that there was something wrong in the running of the country, the economic policy of the government was wrong. For the previous governments, not just only the last government, the previous governments to allow the majority of the workers in this country to be engaged in unskilled jobs was a bad tendency. And for us then to improve that situation, to bring most of the black workers to skilled jobs is also a change in the country. And we have also to take into account that as long as we have not done a complete integration of the police, black and white, under central command, I am emphasising this central command, then things are going to go like a crab. We want to change that situation. The process is getting, even now as I am sitting here, people are discussing this question of integration in Pretoria. I just received a phone call this morning, now that we are busy we will take more time, we will take about a week to finish our business. Once we have the police force in place, complete integration, then we will say to the army, We are no more going to worry you, you can go and help those people who are doing agriculture because there is peace, there is no war. We are in a position to say that.

. Insofar as the crime is concerned, the crime is going to carry on in this country but what we should aim at is to reduce it and I think we are in the process of doing that. We will only be in the process of doing that effectively when we have got a solid, efficient police force and I think we are in the process of seeing to that, that we have an efficient police force in this country. Let me just perhaps conclude by saying that in the past the police were the enemy of the people because they were carrying on with bad laws. Now this is a democratic government, progressive, legislation is being legislated in the legislative bodies, the people now sooner or later are going to embrace the police as their friend. Then you will find that it is easy to arrest the criminals.

POM. When you look around you, as we have for the last three months that we've been here (you know we've been here for most of the last two years, just went home for Christmas and came back at the beginning of February), there has been nothing but a spate of strikes, hostages being taken by unions, taxis blocking off cities, again an incredible level of crime, work stoppages, erratic, could happen at any time. One would get the impression that the country is more unstable than stable and if I were a foreign investor and saw all these things happening, even if I saw like in Umtata where you had a do a couple of months ago when the army had to be sent in and told if you have to shoot these guys, shoot them, this has got to stop, if I was a foreign investor I would be a bit leery. I would say I will wait four or five years and see how things work.

RM. Well foreign investors by the way have got very efficient machinery for getting information in any country. They have got their own people who are making assessment of situations in the various countries before they invest. You are right. But they are fully aware that this change in South Africa is a peculiar change where the majority of the people who have been oppressed are now actually running the country as it were. But they are going to give us that period of adjustment and they are studying it. And from the reports I am receiving by the way, I don't know whether you are receiving the same reports, is that foreign investors are in fact saying already, openly saying, that South Africa is a suitable place to invest in. That is the report I am receiving.

POM. I don't have access to that information since I'm not a Premier (that was a joke).

RM. It's a fact. I am receiving it, I am also reading from local press about the progress of a number of firms in this country, that economic growth is picking up. As a matter of fact I was having a discussion only on Saturday with the Deputy Minister of Finance, saying to me, You know, I am worried, the economic growth is fast. I said to him, You must be careful that it isn't fast coming down. So there is that. I am so happy that it is the business people who are saying, it's not me, who are saying, in fact I've got some friends in the business in spite of the fact that I'm a communist, and they said, Look we are doing well, things are coming right.

POM. Alongside that there have been three reports issued in the last month or so, one by the IMF which painted a very gloomy picture of the longer term future of South Africa, it said growth would pick up this year and maybe next year but after that there would be a downturn. You had a survey by a group called the Future Manufacturers' Survey which rated the competitiveness of different sectors of South African industry against foreign competition and found that in most categories that South Africa was uncompetitive. Many of what I would call the mainstream economists say that part of the problem here is that the level of increase in wages for a number of years has been well in excess of the rate of increase in productivity so that your goods are getting more uncompetitive rather than competitive. Now how do you balance your obligation to working people and at the same time ensure that you are competitive enough to do well in what is now a global economy where you are competing against the Taiwan's and South Koreans and the Singapores.

RM. Well competition is one element in the capitalist social system and I welcome competition, competition is all right. But the trouble with the capitalist social system is the fact that it is survival of the fittest, that is the trouble with it. When you talk about International Monetary Fund they can suppress certain areas, certain countries by certain conditions they impose. That is why at one time President Kaunda got fed up with IMF because they can make you a slave with their conditions. Now let us leave that aside. You know on 9 April I had a breakfast in the Johannesburg Country Club with the big guns in the mining industry. Now they maintain that, we were talking about this question of productivity and wages, and I drew their attention to the fact that when we talk of productivity we tend to be directing it to workers. We don't examine management. In this country, if at all we want to balance things, we must also concentrate on the management. The management in South Africa is something which has to be put right, there is something wrong with it, the management. And they agreed with me. In fact they said you are perfectly correct. They have done a lot of trimming themselves, I am talking about the big guns in the mining in South Africa. That was on 9 April in the Johannesburg Country Club, I had breakfast with them. So as much as we encourage productivity as you see in Japan and Germany and so on, that the rate is high and in this country you need to do certain things to bring about productivity. I used to say before the 27 April last year that when the black man takes part in the political activities in the country then they will feel that they are at home, they have got certain rights and then perhaps even productivity will improve.

POM. Do you think that the country is at a point where workers from all sectors understand, were all in it together and that there must be some sacrifice of individual gratification so that the collective good will be better, more people will be employed, and it will be more competitive abroad? Or do you think it is still at the point where it is each man out for himself? If I can get it, if I can go on strike or if I can have a work stoppage or if I can do this action or that action and get my demands met then my first duty is to myself and let other people look after themselves?

RM. I think in this country we are learning and we want to correct our mistakes. Let me put it this way, that insofar as class contradictions, economic interests are concerned, that contradiction will still be there. You will still have an employer who is aiming at more profit. You will still have an employee who is aiming at more wages and so on. That contradiction will persist, will remain there. But what we should do is to harmonise relations between the management and the employees by creating a machinery, a legislative machinery through which these two bodies are able to meet and discuss problems. I was saying to somebody last month that we are learning in this country because we as a government who took the initiative of calling a summit, where we invited organised labour, where we invited organised business, where we invited, of course we are government, we came in to discuss how we are going to run this province. But the truth of the matter is that we can't say as a government to the workers, Stop demanding more wages. We can't call upon the organised business to say, Stop earning more profit. But these two bodies must accept their inter-dependence, that you cannot live without the other one, because once they accept that fact they will start to discuss problems soberly, but we have gone so far in this province. We called the summit on 7 February in Port Elizabeth. It was successful.

POM. I want to go back to security for a moment. Do the policemen in Bisho still wear the uniform of the Ciskei, and in Umtata do they wear the uniform of Transkei?

RM. Well I'm not sure about that but I think so. You see when we talk of integration, that has also to change to one uniform. I don't even think we should think in terms of a province, we should think in terms of national, that the police force is a police force, the uniform must be the same, the equipment and so on, and I am having a discussion with the Provincial Commissioner of Police to say, Look at the police stations, improve them, they are poor. Transport for the police must improve and a number of things so that the police should feel safe and because we are dealing with criminals who armed, they have got first class motor cars, they can run fast, the police must have all those things to bring the same equilibrium.

POM. Can you ever envisage a situation here, first, where you would call upon the President to declare a state of emergency or where you would ask him to exercise under the constitution, his constitutional right to invest the police with more power?

RM. What more power are you thinking about for the police? You mean arrests, things like warrants and so on?

POM. Yes.

RM. Well the question of the State of Emergency, it's a situation which if it is there, there is the cause of declaring a State of Emergency, if it is there we will have to appeal to the President to impose a State of Emergency. Now with the police, dependable on the situation, if there is a need that they should have more powers, they should have more powers.

POM. I was rather surprised when President Mandela revealed that in response to your request for help in the police rebellion in Umtata that he gave the order that if to use live bullets was necessary, use live bullets.

RM. Well, there is nothing wrong with that. You look at that situation. The police organised the blockade, the were armed. If I am meeting an armed man, even a criminal who shoots at me as I am a policeman, do you think that I should wait and not return back? That's illogical. It will be survival of the fittest in that situation.

POM. OK, now I'm going to give you a contradiction. So you had the President who says if you have to use live bullets, use live bullets. In other words if people have to be killed in order to stop this then they have to be killed, and then a week ago he says that human lives are more important than the constitution. A contradiction.

RM. There is no contradiction there, you are using the wrong word, contradiction. There is no contradiction there at all. You are dealing with situations at different levels. I am saying to you it is just logical if a man opens that door armed, he's going to shoot at me here, if I've got a pistol with me I must shoot first, that's logical. If there is a situation which gives me the opportunity of solving a situation peacefully then I must do so. That's all the President is saying. And the President is saying that in a situation which he was dealing with he maintains that human lives are more important. He is dealing with a specific situation and that fits in very well in a less specific situation. Now where the contradiction comes in, there is no contradiction at all there.

POM. When he says that he would amend the constitution to give him the right to withhold funds from KwaZulu, do you have any doubts about that or do you think the constitution should be such that no one person can amend, to suit whatever purpose, it might be for a good purpose or whoever succeeds Mandela might use the same power for a bad purpose?

RM. Now you see the President represents the Cabinet, the government. Now if we are going to make him as an instrument, that the Cabinet is going to make the President an instrument so that that instrument is used in specific situations and if we feel that he lacks the power to perform his task we must see to it that he is given that power by the constitution, through the constitution. There is nothing wrong with that, absolutely nothing wrong. The aim, whether you are in fact protecting or perhaps engaged in a good cause, now the President as I said is dealing with a specific situation where people are being killed in Natal, because you have mentioned Natal, people are being killed there. We know that Inkatha is instrumental although Inkatha is throwing it back at the ANC and saying it is the ANC. But what is happening today? There is a campaign going on. The Inkatha leadership is advocating civil war. Do you want to tell me that the government should sit down and fold its arms? There is a man arming, advocating war, and you are not preparing for that eventuality, then you are not fit to run the country. He is saying that since there are people who are planning to kill, to diminish human lives, to reduce the human lives, I must protect that, but I haven't got the power, give me the power, let the Cabinet give the President power.

POM. You would have a good reading of Chief Buthelezi over several years, do you think he is engaged in, again, a form of brinkmanship?

RM. I think so.

POM. That when it comes to the crunch he will ...?

RM. I think so. You see he is that type of a human being when he sees a crowd he loses his balance, he is that type of an individual. It's dangerous a person like that. And a person like that he must be harnessed, he must be not allowed to abuse his privilege or his democratic right.

POM. Just in your own personal opinion, how are we doing? One or two last quick questions. You have kind of an unstable Buthelezi over here.

RM. He has been like that even before April 27 last year.

POM. What I'm asking is, do you think that as far as he would push this situation with regard to international mediation and urging his followers to rise up and resist the central government, do you think when it comes to the crunch he will find a way of backing down? Or do you think he's very good, and he will back down, he always gets a concession or two?

RM. Well the trouble is that he has been treated very softly by this government, Buthelezi, and if I was in the boots of the President I should have been a little bit firmer and harsher on him. You can't allow individuals like the right wingers, at one stage they were allowed to go about organising as if for civil war, and you know that, you are a government, and you don't take action. They are arming themselves. You know at one stage this group of right wingers were arming themselves and the government was not taking action and there is Buthelezi, we know that there are certain people who have been sent to military camps to be trained and we are not taking action at all. I am against that.

POM. This is on Transkei and Ciskei. When you took over and you had auditors look at the finances of Transkei and Ciskei it would appear that the books of the Transkei were in utter, complete disarray with people unable to account for billions of rands. How did the Ciskei fare? Was it as bad or nearly as bad, or were their books better?

RM. It does better than the Transkei.

POM. A lot better? Because the way you talk about the Transkei it was so bad that to be better doesn't - you are still bad.

RM. No, I am saying Ciskei was better off than the Transkei. Transkei is in a mess. You come to this project, the dam irrigation project, so many millions are owing right through. And as you say, no proper bookkeeping and all that. But fortunately enough the central government is fully aware of the situation and I know by now that they are prepared to help us, even financially.

POM. Two last questions. One is that you fired two ministers, the Minister for Safety ...

RM. Don't fight with me now!

POM. OK. So I'll leave that there for a moment. Then some months ago Popo Molefe fired a minister and the thing went before the National Executive of the ANC who said find a way of giving the man back a job of equal standard or whatever in the interests of harmony. In effect Popo said, Well, not so quick, that the fundamental right of any Premier is the right to hire and fire who he wants to be in his Cabinet. But in a way here you had the ANC superimposing itself as an organisation above the provincial leader and saying, No, no, you must do what we tell you to do. Now did you go through any of the same ...?

RM. No. The ANC has never interfered with me.

POM. You can hire and fire who you like?

RM. I am just doing my work, nobody has interfered with me. And I will tell them that I am a government. By the way I am a member of the National Executive of the ANC and perhaps I am fortunate they haven't come to me at all to say that, look you must march this way, you must step this way and so on.

POM. I found that troubling. I found it troubling in the sense that the first right of a Premier is to hire and fire who he likes.

RM. That is the constitution, it is in terms of the constitution, yes.

POM. So this thing of the party putting itself above the Premier to me has disturbing implications.

RM. Well I think that we must accept the fact that we are all members of the ANC by the way, I mean strictly speaking the ANC should be concerned about what we are doing and it's a question of a specific case. I have handled two cases now and I have never been interfered with by the ANC at all. Quiet. Not a word.

POM. They must know you're a tough old bird. OK, have you maybe got anything that you want to add?

RM. But when I am in trouble I want some of them to come and I go there and say I want this and this and this. I have got Zam Titus here, I have got others here, and it was tough.

POM. Thank you for your time, thank you very much.