This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

Overview of 1989

Following a stroke in January 1989, PW Botha, the surviving member of the Verwoerdian era, relinquished the leadership of the National Party to concentrate his energies on being State President. FW de Klerk was elected leader of the NP. Botha's decision to separate the two posts effectively hammered the first nails into his political coffin. His behavior became increasingly erratic and rambunctious and a distraction to his colleagues, especially De Klerk. In August, after the National Party caucus finally confronted him, Botha went on national television and after a long, rambling and frequently incoherent tirade during which he accused his colleagues of betraying the Afrikaner volk, he resigned and retired to George to write his memoirs in Afrikaans, thus ensuring them a secure place on the shelve of obscurity. (It says volumes about the grip he had held on the party for 20 years that even when he had become a crippled old man, often incoherent in his utterances, an embarrassment to the party while he retained the position of State President as the NP approached a crucial and defining election, and for the caliber of leadership in the party that no one in the caucus actually wanted to be the one to take Botha on face to face and tell him that the time had come for him to step down either gracefully or risk removal for being incapable of carrying out his duties De Klerk, with reluctance eventually broke the news to Botha, surrounded by his conspiratorial colleagues).

Botha met with Mandela in July 1989, had him whisked secretly from Victor Verster prison to Tuynhuys, the State President's official office in Cape Town, had the two of them photographed shaking hands, and passed around a copy of the photograph the following day to his incredulous cabinet, a mischievous smile creasing his usually stern countenance, taking silent glee in having gotten away with a little naughtiness, of having trumped his colleagues with an ace they could never match, of putting one over on them behind their backs.

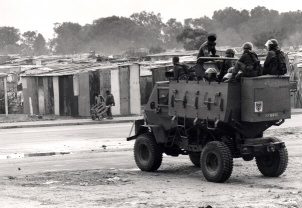

Two states of emergency -- in 1986 and again in 1987 had not put a stop to the township violence. The state itself had hit the wall, had exhausted all options because an inevitable extrapolation of the implications of every option available to the government led to the same inexorable conclusion: apartheid had to be dismantled, even if the consequences were too terrible for the white minority to contemplate. Looking down the road the government could see nothing but an endless cycle of violence and repression, each feeding off the other until things simply fell apart.

Moreover, the external climate was rapidly changing; Michael Gorbachev''s doctrines of glasnost and perestroika and the impending end of the Cold War left the South African government in a quandary.

Once the regime could portray itself as the principled ally of the West in the war on Soviet expansionism, especially in Africa. It could always count on the covert support of the United States and a tacit tolerance for apartheid the way forward would be along the path of an amorphous constructive engagement rather than outright condemnation of apartheid and the support of whites at home. When the foundations on which these relationships were rested began to crumble, the validity of policies that were their support base came under scrutiny, and the scrutiny exposed the bankruptcy at their core.

The axes on which the world's international and economic orders gravitated had changed. The ideological axis had collapsed; the economic axis had been replaced. Massive and fundamental changes were necessary not because they were desirable; they were an inevitable outcome of the changing order of things, an emerging world order, yet in its gestation, unfocused regarding the directions it would take, itself bewildered by the rapidity with which the old order was being swept away. South Africa was in the way of the sea flood of change. It could either resist the flood and be swept away in its deluge or embrace it, and find itself on a different shore.

South Africa or at least white South Africa was beginning to wrestle with a conscience it was unused to consulting. On the one hand, whites knew that the fundamental principles underlying its own sense of identity were irreverent, inducing both a sense of bewilderment and defiance. On the other hand, it had no clear idea what the future would bring, except that it would be very different, and probably most unpalatable. The realization that they would have to create a more inclusive dispensation was not something that struck like a bolt of lighting; it was something they always knew was going to happen, but they had closed their minds to what it would entail, and had hoped that by living in a state of perpetual denial, they could postpone the inevitable indefinitely.

But because they had so assiduously avoided engaging themselves in dialogue, indeed, were actively discouraged from doing so, they found themselves facing a void: what was would no longer be, but what would replace it was uncharted -- they had no map to guide them across the political terrain that they had to cross, and their impulse, as always, was to withdraw, opt for the status quo that would serve as the vehicle for changing the status quo, and hope, against their better instincts, that the changes, gathering like clouds on the horizon, would miraculously dissipate and do little to disturb the tranquility of their Christian lives. Having lived in calculated ignorance of how they were governed, what happened on a day-to day basis in their country, they would, by and large, opt for change, not because they wanted to, but because they had to.

In August, national elections were held and the NP, under the leadership of de Klerk was returned to government with a reduced majority-with 93 seats out of 175 rather than the 133 it had previously held. It lost support to both the right-wing Conservative Party, which increased its representation from 17 seats to 39 -- and to the liberal Democratic Party, which captured 33 seats. But for all the seriousness the parties attempted to invest the elections with, they knew that they were participating in the last "whites only" election South Africa would hold. Not that anyone would say so for that would be tantamount to saying the emperor had no clothes, thus begging the question of where were the clothes to dress him.

De Klerk, now State President and leader of the NP, declared that the seventy percent of the white electorate who had voted for either his party or the Democratic Party had given him a mandate for constitutional change that would extend the franchise to Blacks and give them a role in government. What the nature and scope of that role would be, and how and when it would be implemented were, of course, matters that Whites only would decide. In short, if Blacks were given a role in government, it would be on white South Africa's terms and in white South Africa's time.

For a time those terms were unequivocal. The unique democratic dispensation that must be developed in South Africa," according to the NP's election manifesto, "cannot, as in the past, solely rest on the premise of 'winners take all."

The ANC had little to say. In the Harare Declaration, it had set out the conditions, which it said would have to be taken unto account, both in terms of process and procedure, in order to chart the country's path to a democratic non-racial society.

2

During the 1980s, the apartheid regime had lurched uncertainly from one reform to the next, but could not face the prospect of taking the ultimate step: having to abolish what it could not reform, that only the dismantling of the entire apartheid apparatus, the enfranchisement of the masses, one person, one vote, the handing over of power to the Black majority would suffice and open the way to a democratic dispensation. The ANC regarded every overture the apartheid regime hinted at as one more manifestation of its cunning: "yes," the ANC said, it would negotiate, but negotiations had to lead to fundamental change; "no," it would not negotiate if negotiations were intended as cosmetic adjustments to government designed to keep power in white hands.

But events were now conspiring to undo the government's capacity to control the political environment in which it operated and which, for the better part of fifty years, it had manipulated with great dexterity, and even greater ruthlessness. The law was eroding, but more importantly, you were witnessing not only the erosion of law, but also an accelerated process of defiance. Besides, in spite of the government's recalcitrance, South Africa was changing structurally. There were processes at work that couldn't be measured either in terms of laws or government dikats, things the government itself seemed slow or unable to discern. The government continued to believe that since the laws relating to apartheid weren't being changed, because white voters weren't showing any predilection for change, that nothing in society was changing. On the contrary, everything was changing.

One of the ironies of history is that elites who oppress others often provide their offspring with the best education power can buy, thus ensuring, unintentionally, that their offspring have a more "liberal," more broadly encompassing worldview than they themselves do. And the offspring, once they "inherit" the mantles of power, move in new directions, directions that are in most respects a renunciation of all that their intransigent forefathers stood for.

The heirs- apparent in South Africa, especially those who were elected to parliament in 1987 -- the "class" of '87, as they liked to refer to themselves, began to assert its independence from the old guard the generation that had written and implemented apartheid legislation. The new NP MPs knew that the old order was on its last legs. Most of them were young, had traveled, some extensively, had found themselves having to defend apartheid when had stayed, as students, in hostels throughout Europe and elsewhere, were aware that South Africa could not survive, isolated from the rest of the world and crippled by sanctions. Most importantly, they knew that apartheid was morally indefensible.

And then there are the practical realities that make the need for an accommodation more pressing. In many conversations "those-in -the-know returned again and again to a continuum of events that would suggest, if one were to make logical deductions, that things were coming to a head, that the pressures on the government, both internal and external, to release Mandela immediately and dismantle apartheid in its entirety were becoming intense, and that the government's response, under the new leadership of De Klerk, augured well for some substantive dialogue with the ANC to get under way. Apartheid was now being talked of in the past tense; the debate had moved to configuring the political ramifications of a post apartheid order and the governance structures that would emerge.

To the Afrikaner, long beholden to his laager mentality, the obvious was, at last, becoming obvious. His choices were narrowing, and the longer he waited to become proactive rather than reactive to the swirling vortex of the inevitabilities he had to confront, the more he was losing his capacity to control their outcome. At some point self interest had to assert itself, and self interest dictated that he would have to do that which he had vowed never to do talk with the legitimate leaders of Blacks about legitimate Black demands, which meant, of course, talking to the ANC. He could do it now. And gain some. He could do it later. And gain nothing.

Self-interest is a perquisite for survival, and the Afrikaner had made an art of the practice. He could argue that the ANC's military campaign was more imaginary than real; that if pushed, the government could reassert its authority over the townships now in the hands of young Blacks, even if the price it had to pay would be horrendous. He could argue that he could hold onto power for at least another twenty years, but he would be making the argument from suppositions that might or might not be invalid, and even if thy were valid, he would have been missing the point: A day of reckoning was inevitable, and that if he continually tried to postpone that reckoning, he would have to face it with an empty hand-alone, isolated, and without support. He would, of course, in the self-destructive decision to cling to all power at all costs ruin his economy and with it the source of his power.

Between 1908 and 1948, the world had changed a hundred fold; between 1949 and 1989 it had changed a thousand fold. Unless he got off the fence of history, he would not become one of history's casualties; he would do better. He would become extinct, a historical fossil, worth perhaps the usual crop of doctoral dissertations, but little more, a footnote in the literature of how nationalities consumed with preserving their identity consume themselves. The grim reality of the undisputable was bearing down on him with a terrifying intensity.

However, although the demise of apartheid and rule by the majority in South Africa was perhaps inevitable, when it might occur and under what circumstances were far less certain. In many conflicts, the antagonists independently reach the conclusion that while they cannot defeat their opponent; neither can their opponent defeat them. But not until these realizations become congruent does a situation arise in which both are able to set in motion the actions that lead them step by step into a sustainable negotiating process.

3

In South Africa, a number of factors colluded and converged hastening the recognition by the government and the liberation movement that negotiations might yield greater dividends to both than a continuation of a conflict that neither could win or that either could win but at a cost that would perhaps irreversibly damage the long term interests of both.

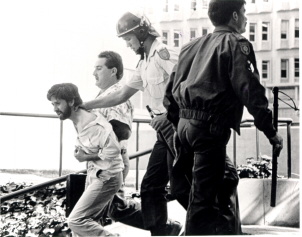

The government had to concede that repression hadn't worked, that while it could put a lid on mass mobilization, crippling strikes, boycotts, and the permanent state of unrest in many townships successive states of emergencies created the conditions for fermenting the conditions that led to the upheavals in the first place. Nor were confrontations with the state confined to political issues, although the state's ham-handed ways of dealing with them invariably ensured that they would become political.

The rise of the civics community organizations dealing with issues Blacks faced in their daily lives shortage of housing, of social infrastructure, education, discriminatory laws, made every issue an issue of grievance and thus an issue of protest in the absence of state action to alleviate it. Moreover, the civics, with their emphasis on grass roots organization became an instrument of empowerment; each small victory over the state encouraged communities to believe that another victory on another issue was possible, that protest yielded results, adding to the momentum that saw the cumulative number of protests increase exponentially to the point where the end of protest was protest itself. Every issue provided its own terrain of struggle.

Moreover, the frequency of the phases of resistance had doubled -- sixteen years between 1960 and 1976; eight years between 1976 and 1984; and four years between 1984 and 1988. The intensity of resistance in each phase had increased. Mobilization had become a structurally ingrained, permanent feature of society. At least two generations of Black youth in the townships knew nothing but mobilization and resistance.

When the ANC went public with the Harare Declaration, it signaled to the regime that it was open to a negotiated settlement provided the state could show that it would act in good faith and thus the preconditions that the state would have to meet to manifest good faith. They included the release of all political prisoners, the unbanning of organizations, and the lifting of the state of emergency. For its part the ANC reiterated yet again that it had turned to armed struggle only when all other avenues of protest had failed to yield any results, that the goal of the armed struggle was not the seizure of power, but to bring the regime to the negotiating table.

The Harare Declaration called on all parties to the South African conflict, including the South African government, to take part in peaceful means to end the political deadlock. The ANC insisted on a status of equality at all stages of the negotiating process. Pretoria would be at the negotiating table as merely one of the parties -- not the dominant party calling the shots.

Few in the ANC believed that MK could defeat the government' military power. In the early eighties there was a spurt of armed activity including sabotaging SASOL's refinery and the attack on the Koeberg nuclear power station, but after South Africa and Mozambique signed the Nkomati Accord in 1984, ANC bases in Mozambique were closed and with them the most effective routes for MK penetration into SA. Although the ANC's political propaganda depicted the armed struggle as a full scale peoples' war against the South African state, the reality at the end of the 1980s was that despite the efforts of Vula, only two members of the NEC were in South Africa conditions were never quite secure enough to convince either Tambo or Slovo that a more wholesale influx of the top leadership warranted the risks involved.

While there were 281 cases of what the government calls "terrorist incidences" in 1988, the 1989 figures are considerably lower: 162 incidents between January and September, and only six incidences in October. Its activities were peripheral to the direction events were moving, despite the fact that ANC strategists in Lusaka continued to push the armed struggle at the expense of building an internal political underground even though they were fully aware that the existence of the latter was a necessary condition for the sustained success of the former. As best, the armed struggle had become a powerful symbol of mobilization, particularly for Black youth for whom militancy was an essential part of the culture of resistance. Yet, there was no question of the ANC disavowing the use of violence in the absence of major concessions from the state. Otherwise, a unilateral action of such a magnitude would undermine the ANC's credibility with its cadres, incite rebellion in the camps, and wreak political havoc among the militant youth in the townships where the call for armed struggle was becoming louder and more insistent.

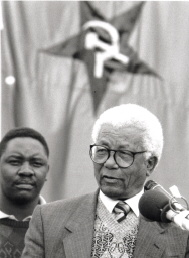

The Mandela factor loomed large in the state's assessment of what moves to make and when. Mandela met with Minister of Justice Kobie Coetsee on a number of occasions and on close to 50 occasions over a two year period with a team of government officials, headed by Neil Barnard, head of the National Intelligence Service. P.W. Botha's invitation in July 1989 to the imprisoned Nelson Mandela, leader of the ANC, to join him for tea at his presidential residence had powerful symbolic and political implications. Members of the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) -- were visiting Mandela on a regular basis at his prison bungalow.

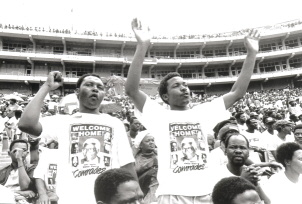

The release of Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba and Ahmed Kathrada in October 1989 meant that Mandela's release was only a question of time. It moved from the realm of speculation to expectation. Once the government released Mandela it would, of course, have to talk to him -- the government would, in effect, be unbanning the ANC and committing itself to negotiations with it and other mass-based organizations.

Meanwhile the political geography of the world was undergoing wide ranging realignments. The enormous changes in the Soviet Union, the upheavals in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and East Germany, the indelible symbolism of the Berlin Wall literally being torn down by Germans on each side signaling the collapse of Communism, the implosion of the Soviet empire and the end of the Cold War; the restructuring of Europe; intimations of further changes in the Soviet Union, its willingness to cooperate with the West in the settlement of regional conflicts, its withdrawal from Afghanistan and the collapse of its expansionist proclivities; and its constructive role in the South Africa/Angola/Cuba/Namibia negotiations undermined the ideology that was the centerpiece of the Total Onslaught strategy. The enemy was no longer real.

With no Total Onslaught with which to stiffen the will of the White population, the Total Strategy that coupled security and reform in the interests of national security lost its ideological heart. In "The Long Trek," De Klerk says very matter of flatly, ' with the fall of the Berlin wall in November 1989 one of our main strategic concerns for decades the Soviet Union's role in Southern Africa and its strong influence on the ANC and the SACP had all but disappeared. A window had suddenly opened which created an opportunity for a much more adventurous approach than had previously been conceivable.'1

The collapse of communism, the disintegration of the GDR and the Soviet Union's preoccupation with its own matters of state and governance also had ramifications for the ANC the loss of financial support, service resources and military hardware for a prolonged 'people's war' curtailed its capacity to play as opportunistically on the world stage as it once had. Even a struggle that had spanned the better part of a century lost some of its purity of purpose when the purveyors of nobility were in decline.

The settlements In Namibia and Angola were a harbinger of impending change in South Africa. With independence for Namibia, the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola, and an end to South African support for UNITA, the securocrats lost both prestige and influence while the diplomats in South Africa's Department of Foreign Affairs were catapulted into more prominent and influential positions, a shift in the balance of power between the two further emphasized when De Klerk ordered the dismantling of the NSMS, downgraded the SSC and re established the Cabinet as the primary organ of government decision making.

South Africa's efforts in this regard were part of a wider diplomatic offensive aimed at breaking down hostility to South Africa on the continent. As if to symbolize this, in late August 1989, De Klerk visited Kenneth Kaunda, President of Zambia, in Lusaka where the ANC maintained its headquarters. The visit signaled a detente of sorts between the frontline states and South Africa. He visited Joachim Chissano, President of Mozambique in Maputo. The point is: South Africa was learning that it could negotiate differences with its neighboring states without equating every compromise with surrender. Foreign pressure, especially from Margaret Thatcher facing demands from the Commonwealth nations for tougher sanctions against South Africa, had a bearing, too. For the U.S. 'constructive engagement' assumed a different nuance in a post Communist world.

The economic deterioration of South Africa continued through the 1980s: Double-digit inflation, increasing unemployment, not only among Blacks but now affecting marginal Whites, a balance of payments deficit, shortages of foreign reserves, the absence of inward capital investment, the falling value of the rand --all aggravated the situation. Trade sanctions do not appear to have had much impact, but the financial, capital, and technological sanctions had severe repercussions, slowing the growth of productivity, eroding the country's skill base, and weakening its physical and material infrastructure.

The outgoing Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, Dr. Gerhard de Kock, warned that South Africa's economic situation could never be resolved without real political change. Depending on whose data you use, you can make the case that White South Africa's real purchasing power had not gone up since 1980, or that there has been a fifteen percent fall in the standard of living in the last four years.

The average rate of taxation was 52%. Inflation, still rising, was at 15 per cent. Public expenditure paid for a swollen civil service, an inefficient quadruplicate system of governance and the enormous subsidies the central government pays to the Independent and self-governing Homelands to maintain the myth of independent Black Nations. When the major western banks, led by Chase Manhattan, called in their loans in 1985 after Botha's aborted Rubicon speech, the maturity profile of the new repayment schedule skewed the South African economy, effectively bringing economic growth to a halt so that the country would not default on its loan commitments. But short of defaulting the country was bankrupt.

Moreover, the economy, increasingly dependent on Black labor, was also increasingly vulnerable to the activities of the Black trade union movement, which emerged as a powerful political force in its own right. The three-week nation-wide mine workers' strike involving 250,000 Black miners in April 1987 crippled South Africa's economically crucial gold mines and a quarter of its coal pits. The 900,000 members of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the 300,000 members of the National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU), which between them represented more than one-sixth of the Black labor force, increasingly used their muscle to advance a political agenda.

On Election Day, 1989, they called on Black workers to stage a one-day general strike to protest the elections. Some three million African workers stayed away from work -- a number that exceeded the total number of whites, Coloureds, and Indians who went to the polls. The reality of the situation was that the Black unions could bring the economy to a halt on any given day; not everyday, but in short sporadic bursts that were more disruptive because they were unplann

Business decided that apartheid was bad for profits. The international isolation of South Africa had an impact in South Africa's corporate boardrooms. In July 1987, leading members of the White business establishment went to Dakar, capital of Senegal, to meet with representatives of the ANC, and the two sides found themselves agreeing, to quote from their joint communiqué, that "there is an urgent necessity to realize the goals of a non-racial democracy." Subsequently, there were many more delegations of businessmen, academics, writers, and other influential sectors in South Africa to Lusaka or Harare or other locations outside South Africa to meet with representatives of the ANC. These meetings did much to dissipate the propagandist image of the ANC as the standard-bearer for a Marxist/Leninist South Africa, which would abolish the free enterprise system and destroy the market economy.

The ANC did its part. In August 1989 it released 'Constitutional Guidelines for a Democratic South Africa, --the Harare Declaration in which it specifically stated that, "the economy should be a mixed one, with a public sector, a private sector, a cooperative sector, and a small-scale family sector." In short, the business sector, it was saying, had nothing to fear from an ANC-dominated government. Business, faced with continuing catastrophic scenarios of a country either driving itself deliberately out of business or being driven there by its external creditors, was becoming increasingly responsive to the message. Having to choose between the devil it knew and the devil it didn't, the devil it didn't was a more attractive choice.

The demographic trends were unmistakable and irreversible. Demographic forecasts in the late 1980s, which, of course, took no accounting of the impact of HIV/AIDS, suggested that South Africa would experience a 144 percent increase in population within 35 years, at which point the Black population alone will exceed 56 million people. The White minority would become an even smaller minority, unable to provide the manpower from its own ranks at any level of management to maintain the apartheid system. Indeed, labor demands had already eviscerated influx control laws and the Group Areas Act. Accelerating urbanization simply steamrolled its way over most of the restrictions imposed on the movement of labor by apartheid legislation. By the mid 1980s apartheid had become unworkable, overwhelmed by the rigidities embedded in its racial ideology, an anachronism in a rapidly globalizing world where competitiveness was determined not by the colour of your skin but by the level of your productivity.

White South Africa, therefore, was faced with two choices. Either it could wait for the inevitable to happen when demography simply made its position untenable and impossible to hold -- a situation in which the Black majority would be, in all likelihood, not particularly well disposed to dealing with sympathetically -- or it could negotiate a settlement now that would allow it to hold on to some of its privileges, even it if means a substantial loss of its power.

South Africa would need a five percent annual growth rate in Gross Domestic Product, just to accommodate the rapidly increasing labor supply. At best, during the seventies, the annual rate of growth was under four percent, and in the eighties it was less than two percent. Per capita income in real terms was falling and would continue to fall without a fundamental restructuring of the economy, a restructuring that will be possible only if it is accompanied by unprecedented and far reaching political change.

In its 1989 election Manifesto which the National Party showcased as setting out the principles that would underpin the new South Africa it envisaged it posed the question: 'Can a Black man, in terms of National Party policy, become State President?" The answer: "The position of State President can be an important symbol of national reconciliation and should thus enjoy the support of all groups. Although this issue is not on the agenda now, it is important that all groups be able to participate in the election of the State President. However, it is the National Party's premise that domination of any one group by others should be avoided. It is thus necessary that the electoral procedure, as well as the character and the responsibilities of the Office of the State President, be reconsidered in order to prevent the office from becoming an instrument of domination." Which meant, when you cut through the verbiage, yes, no, and maybe.

No matter how one looked at the matter, it was clear that the days of a monolithic Afrikaner nationalism ruling an Afrikaner State were over. De Klerk faced a task no other leader of a national state ever dealt with: he was being called on to be the instrument of the government's demise, in effect, to preside over the dissolution of the Afrikaner state, put himself and the national state he led out of business. If he moved at the pace anti-apartheid activists demand, he might lose the support of his white constituency and trigger an inexorable right-wing backlash that would topple him and plunge South Africa into unprecedented racial war.

To the extent that the South African government appeared uncertain how to proceed, it appeared vulnerable. It had lost the psychological advantage its heretofore aura of invincibility had enabled it to enjoy, thus encouraging the Mass Democratic Movement to believe that for the first time it had the government on the run. When the future threatens, however, there would be strong pressure on the government to resort to the strategies of the past: In other words, to repress ruthlessly and excessively.

On assuming the presidency in his own right De Klerk inherited a bureaucratic nightmare to all of which it should be pointed out he had given his enthusiastic blessing. The "tricameral" system of government, Botha's answer to the irresolvable problems of apartheid, had produced a gigantic bureaucratic monster swollen with a voracious appetite for resources that had ground it to a standstill.

The central government bureaucracy included departments to manage "general affairs," as well as three departments to manage "own affairs" African, Indian, and Coloureds. Each of the four independent states and the six self-governing homelands had departments that duplicated the national bureaucracy at every level, one department for every line function at the national level. Thus you had 16 departments of agriculture, industry and trade, health etc. -- an endless proliferation of bureaucracies, multiplying exponentially in response to every contingency. Thus, the 47 proposed Regional services Councils, the 15 interdepartmental committees, and further proposals for 9 Black Regional Councils. South Africa had five Presidents, nine chief ministers or chairmen or councils of ministers, 14 cabinets or ministerial councils, close to 300 Cabinet ministers, over 1,500 members of parliaments or other legislative bodies, and tens of thousands of local councilors.

More than 10 per cent of South Africa's labor force worked in the central government, and over a third of all employees worked in the public sector. By 1988, the total wage bill for the public sector came to 60 per cent of the national budget and almost one quarter of GNP. 2 In the 1987/88 budget, a "conservative" estimate of security spending pegged it at between 25 and 30 per cent of the national budget, or between 8 and 9 per cent of GNP.3

The NMS was superimposed on, complemented by, and ran in parallel with these mind-boggling layers of bureaucracy. After 1986, it assumed what virtually amounted to absolute control of government. It oversaw 12 Joint Management Centres (JMCs), 60 sub-JMCs, 448 mini-JMCs, and thousands of Local Management Centres (LMCs), each covering the area of jurisdiction of a local police station.4 Through the LMC network, about 600 key officials, tightly coordinated by the SSC, ran the day-to day operations of government.5 Civilian politics were effectively marginalized. Ministers reduced to carrying out the orders of generals who now dictated policy. Civil Servants became the lackeys of the LMCs. The word "Security" was dropped from the nomenclature NSMS. It was renamed the National Management System (NMS) to reflect its intrusion into every aspect of South African society, public and private. It managed "everything."6 South Africa had become a state run by securocrats; whatever pretenses it had regarding itself as a democratic state had become unstuck.

De Klerk took immediate steps to undo the structures the securocrats had put in place and to re establish the primacy of the Cabinet. But in the process he made enemies, and like all enemies they had their own particular ghosts.