This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

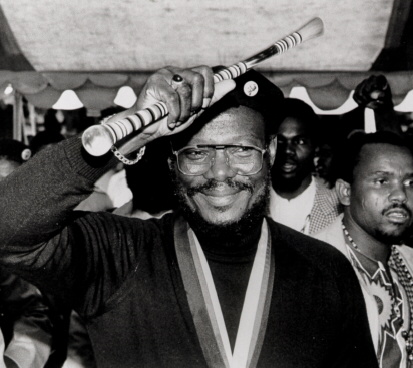

22 Aug 1990: Buthelezi, Mangosuthu

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. I'm talking with His Excellency Dr. Mangosuthu Buthelezi in Ulundi on the 22nd of August. Dr Buthelezi, take your mind back for a moment to State President de Klerk's speech on the 2nd of February. Did what he had to say in that speech come as a surprise to you? And what do you think motivated him to move so broadly and so sweepingly at the same time?

MB. Well, one must first of all give Mr PW Botha credit because Mr Botha was the first person who really wanted to move, to take a new direction but he did not do so, he merely laid the crossroads instead of moving. And all that Mr de Klerk had to do, he has tried to complete what Mr Botha did, a fact which Mr de Klerk himself admitted when I first him, when I had my first appointment with him in Durban with my colleague. He actually said that we must not forget that he had grown up in an environment of apartheid, that his father was a minister in an apartheid government, that his uncle was a Prime Minister of a government that believed in apartheid, and that when Mr Botha said that apartheid must go, it was traumatic, not only for other Afrikaners but even for himself and he therefore admitted that there must be a move away from apartheid. So then, in regard to your question, Professor, concerning the 2nd, I wasn't really surprised. I can only say that I was surprised that he went as far as he did.

POM. What do you think motivated him to go as far as he did?

MB. Well, his sense of reality, and he said so himself that Mr Botha told them that they must move away from apartheid. And I think that for a year, my colleagues Dr. Mdlalose, Dr. Dhlomo and two others were nominated by myself, met with five others nominated by Mr Botha, where we tried to identify the obstacles that impede negotiations. And that is that document, in fact, which helped him because one of the points that we made non-negotiable was the release of Dr. Mandela. We said that under no circumstances are we prepared to compromise on that. We are not prepared to go to the conference table unless Dr. Mandela and other political prisoners are released.

POM. What assumptions do you think President de Klerk made regarding the ANC when he decided to unban it? What I mean is, did he think that the ANC could speak for, could deliver the black community?

MB. I don't think so. I've already said that I told him, but as far as they are concerned, I would think that if I was prepared to negotiate with them, they would have been prepared to negotiate with me without the ANC. But I told them that I was not prepared to do that.

POM. Do you think that Mr de Klerk now has conceded on the issue of majority rule?

MB. Definitely.

POM. And that the government accepts the inevitability of black majority rule?

MB. I don't know what you mean by "black majority rule".

POM. Well, I would mean one person one vote.

MB. I think he accepts one person, one vote, yes. But at the same time inasmuch as the Constitution of the United States does look after minorities, in that sense only, he looks for that kind of consideration, that is all, but he is quite prepared.

POM. Yes, I suppose what I am asking is, let's say there was an election and that your party won a majority of seats ...

MB. But that depends on the constitution, Professor.

POM. I said, let's assume, I'm not ...

MB. Why should we do hypothetical things, doodle really?

POM. Well, because I want to establish what on questions I've asked other people regarding Mr de Klerk and majority rule ...

MB. No, but I've already answered, sir. I've already told you that he believes in one person one vote, but at the same time he would expect a consideration be made for the cultural considerations of other people just as for the black minority in the United States, and the constitution does provide for affirmative action and things like that, to safeguard the interests of the minority.

POM. Do you think that the obstacles to negotiation are now, by and large, out of the way and that serious negotiations can begin?

MB. Well, actually there was, it is taking place among black people themselves. But, I mean, by and large the discussion about talks about talks, yes, that'd be the ANC about their own particular problems, are being addressed, I think, very honestly, I would say. So, it is true that obstacles are really rapidly being removed.

POM. So how do you see the process unfolding in the next couple of years?

MB. It depends, of course, on the world of honest talks to enable us get on the conference table. So, I mean, I cannot prophesy how it will be.

POM. OK, I'll talk about the violence, then, in a minute.

MB. So, what I'm saying is that I won't prophesy, I don't doodle. As a politician I never doodle because I don't know.

POM. Well, how would you like to see the talks ...?

MB. I don't know.

POM. How would you like to see them ...?

MB. I want us to negotiate and work on a new constitution, meet everybody who is represented; a constitution in which there is universal adult franchise, a constitution in which there is equality of all people before the law in the constitution, a constitution in which the rule of law is safe-guarded, a constitution where there is a Bill of Rights. Basically, this is what I would like to see.

POM. This would be a negotiating table that would have representation from every political faction or constituency?

MB. Yes, absolutely.

POM. But it wouldn't be elected by a Constituent Assembly?

MB. No. Why? This is a sovereign country, a sovereign state.

POM. Let me ask you in that regard, how would you determine how parties, say, like Inkatha which has widespread support , how should they be represented vis-à-vis a party that would have very small support, or very limited support?

MB. Depends.

POM. How would you weight - let's say Inkatha has 30% to 40% of support, broad-scale. And let's say another party has ...

MB. You mean represented in the discussions?

POM. Yes.

MB. But I think in the discussions, it doesn't matter how small a party is. I wouldn't say, for instance, smaller parties than my organisation, my party, should not be represented.

POM. But would they have the same number of representatives?

MB. I wouldn't mind, really. I wouldn't, no I really wouldn't mind. I'm talking for myself. I'm not saying that it is the ideal situation. I'm just giving you my own opinion. Because, you know, in the case of Rhodesia, you remember, Professor, that, in fact, even the smallest parties were represented and they fell by the wayside on their own. But initially, both in Geneva and also back at Lancaster House, they were represented. And then the elections sorted them out, you see.

POM. So, would you see agreement arising out of this negotiating process by consensus?

MB. We have the same cultures that have worked very well in the case of the KwaZulu/Natal Indaba here, which was our particular project. So I think that even there I have seen that works very well. The consensus formula works well. But I will not predetermine how the thing is going to be done because that should be decided by people around the table. It is not for me to dictate how it should go.

POM. But the Indaba model provides a paradigm of ...?

MB. Yes, I've said that already. I've said that we've seen that work, and as far as I'm concerned, I think that there isn't one way. But I can't just foist this on other people.

POM. Turn to the violence for a moment. What is your interpretation of the violence that has claimed over 4,000 lives?

MB. Well, there are many dimensions of the violence. Some of it is caused by sanctions, for instance. There are a lot of people that are unemployed. Half the population in this country consists of people who are 15 years and younger. You know, the facilities for blacks in the schools and so on are bad and Mr PW Botha himself, by removing Pass Laws and influx control regulations, has also exacerbated the problem in that there has been rapid urbanisation without facilities being provided. And you know, we have a lot of people walking around our cities who haven't got a job. They have pieces of iron and cardboard over their heads. But I would say, also, there is a political dimension. The ANC was committed to the armed struggle, was committed to the armed struggle all along, and when they switched over from hard targets to soft targets, they said that they were starting what they called the "people's war" , every patriot a comrade and every comrade a patriot. And that, of course, was directed to town councillors, black town councillors who got labelled as traitors; policemen were to be killed. The ANC actually beamed into South Africa messages actually urging young people to kill all those whom they designated as collaborators and that included anyone who didn't support their strategy of violence.

. So, there is that aspect as well. Because the violence that has occurred first occurred in the Vaal Triangle in 1983-1984, where they killed town councillors and where there was a lot of necklacing, which prompted Archbishop Tutu to say that he would take his sermon and go away if black people do this to each other. But it continued. And then the government clamped on state of emergency measures in the whole country. And now the hate isn't removed in this part. It has resurfaced, that's all. That's all that has happened. This is not something new. So, also, there is the social-economic aspect, the political aspect. There are many aspects of the violence.

POM. Do you see the violence as a concerted attempt by the ANC/UDF/COSATU alliance to wipe out Inkatha as a political rival?

MB. Well, I don't know that I would say Inkatha only. I would say that any other party, including Inkatha. Because they have unleashed this violence not only against Inkatha, they've unleashed it also against other organisations. Whether it was in the Eastern Cape, whether it was PAC or AZAPO.

POM. So you see them ...?

MB. But, then, of course, we are much more bigger than these organisations. Maybe then they concentrate on us because they see us as the biggest obstacle, precisely because they see or perceive themselves as a government waiting in the wings, in exile. And, therefore, I don't think that even if they say they are prepared to accept other parties, that they have abandoned the idea of being a government waiting in the wings. They see us as an obstacle to that. And I think that they have not abandoned also the option of the winner-takes-all option. That's also their option, even if they don't admit it.

POM. Do you think they want to establish ultimately a one-party state?

MB. Well, that was their policy in the past, actually.

POM. Now, at one point, you were quite close to the ANC, or so we understand.

MB. At one point I was a member of the ANC. It was started by Zulus, in fact, after the Zulu rebellion of 1906. The man who started the ANC was my uncle whom I knew as a young man, Dr. Seme.

POM. What happened over the years to drive you away?

MB. Well, I think our differences, Professor, already are on record. I reject violence, I reject sanctions. We differ on those things with them.

POM. But those are two points ...

MB. But in the aims and objectives, we don't differ. We have had a very good relationship with Mr Tambo all these years. Mr Mandela, he has corresponded with me, and so on. So, I mean, there's no point in saying "at one point" because, I mean, they only turned against me because I would not embrace violence and because I would not accept sanctions.

POM. Why do you think that Mr Mandela will not meet you?

MB. Well, he has said so. I don't really have to think about that. He has said that his colleagues, when he suggested meeting me, almost throttled him. That is on record. He said that he was almost throttled by them. So, I mean, we don't need to sit back and think because that is what he's saying himself.

POM. And what will, I mean, it's not just the armed struggle and sanctions that would account for the incredible level of animosity between supporters of the ANC and the Inkatha.

MB. But I would have think, I would have thought, sir, that we have covered a lot of field. I have already explained the ideological side, the tactic side, I have already said how they perceive themselves, I have already said that they see me as an obstacle, they see anyone else as an obstacle, but even more so Inkatha and myself because we are big. I have already referred to their ideal of being a government waiting in the wings and so on. So, I mean, what more can we give? Because this is exactly what's happened.

POM. To what extent ...?

MB. Then they removed an obstacle, what they see as an obstacle, so they can be free, they can have a field day by themselves. And be the sole representatives of black people. Because by being members of the United Nations, being allowed, rather, to talk at the UN and OAU they are portrayed as being the sole authentic voice of black South Africa and they are rather jealous they got there, and that's partly the reason they are vicious about this.

POM. To what extent does the violence of recent weeks stand a chance of becoming more ethnic, so that rather than being political ...?

MB. Well, I don't know about that. Your guess is as good as mine.

POM. But, increasingly, it would appear that the Zulus are banding together because they feel they are being attacked as Zulus.

MB. But, of course, that isn't true, as you know, Professor, yourself. You know that they have directed their marches on 2nd July - I don't know how long you have been in this country. On 2nd July there were stayaways where they forced people to stay away, directed at the Zulu people. On the 7th, there were marches. Last week there were advertisements where they said, KwaZulu must be dismantled. I mean, they direct it on the ... and that's what makes Zulus feel they are at the receiving end of their animosity.

POM. Why is it that agencies from the outside, say, for example, like the South Africa Council of Churches, point the finger of blame at Inkatha?

MB. Well, I would say, Professor, for a long time they were very hostile. The SACC has a long history of hostility towards us. And because in the past Archbishop Tutu identified completely with ANC, he said that he supported ANC but not what they do. And more than that, he was actually the patron of the United Democratic Front, which is the front for ANC. And when he retired he was succeeded by Dr. Beyers Naude, who is even now a patron on the ANC. It is not mysterious. And Reverend Chikane is a former vice president of the UDF. So, I mean, there is your answer.

POM. As you look at the future, first, can there be meaningful negotiations if, in fact, the violence continues at the level it is at?

MB. No, I agree, there can't be.

POM. What do you think must be done to bring the violence under control? You mentioned that you and Dr. Mandela should address joint peace rallies. What steps in addition to that should be taken?

MB. They should be discussed by parties concerned. They should not be foisted by myself. The main thing is that we should get together and take it together. And the government, of course, has an input and they do try to deploy more security forces, but I don't know how thinly spread they can be if it flares up in every direction as it is doing now.

POM. What messages do you think, again, the violence in recent weeks, particularly the extent of it, sends to whites?

MB. Pardon?

POM. What message do you think the violence of recent weeks sends to white people?

MB. Well, if I was white, Professor, I would say that if these louts do this to each other, what about maybe the whites killed? It would really strike the fear of the Lord in me.

POM. Well, we've heard a lot about this thing called 'white fears'. In your view, what are white fears and which ones might have a basis in fact and which ones might be purely imaginary?

MB. Well, whites are Africans, you know. I have always said that. I will call them Africans when they behave like Africans because they are, in fact, of Africa; they are not expatriates. But the point is that because of that they know what has happened in Africa to minorities. If they have any sense they would know that what happens to other minorities might happen to them.

POM. What about the right-wing? Do you see the move of a significant amount of white support to the Conservative Party as something that could derail the negotiating process? Is the threat of right-wing violence a real threat or not?

MB. I'm very worried about it, Professor, honestly. Because I believe, myself, that it is one of the biggest threats to peaceful negotiations taking place. And I think therefore it is tragic that we black people are fighting each other because time is of the essence here. It is really very urgent that we should get our act together soon. Because the longer it is delayed the more the right-wing will gain.

POM. President de Klerk has promised to put whatever new constitutional dispensation is agreed to before the white electorate for their approval. Is that a promise that he can keep or that he must keep?

MB. Approval?

POM. President de Klerk has given an undertaking that any new constitutional dispensation that is reached would be put before the white electorate for their approval. Is that a promise that he can keep or it a promise that he must keep?

MB. I think that he will keep it. I think that when Mrs. Thatcher says that they trust Mr de Klerk and Mr Mandela says so and I say so, and everybody says he is a person of integrity, there is no reason why I should doubt that he means it.

POM. But does this not give the white community a veto over any future constitutional arrangement?

MB. Well, I don't know. But those are the facts of the matter. Whether I disagree or not, I don't think that's my business, but I'm just saying, that is the reality we face.

POM. I mean, if you had been part of a team that reached an agreement with Mr de Klerk and Mr Mandela about a future constitutional dispensation, and Mr de Klerk took that and put it before only the white population and they turned it down, would you find that acceptable?

MB. Well, we are speculating here. I prefer to cross bridges when I get to them. Yes, I mean, we are speculating now, we're within the realm of speculation but we'll see when that happens. A lot of things are happening in this country, rapid things are happening in the black communities, in the white communities. We may not even get to that, so I don't know.

POM. What about the economy? There are differences between the ANC and Inkatha on the structures of the economy, you being for free enterprise.

MB. Yes, I am for free enterprise, Professor, myself. But I don't pretend that it cannot be said in this country that our people have been exploited in the past when apartheid was profitable. But I've said that I don't know of any other economic system that creates as many jobs as possible. And we need a lot of jobs, as you can see, in this country.

POM. You would oppose nationalisation?

MB. Definitely. This has been a flop in Africa, a definite flop and has not succeeded in Africa. And, of course, in the mainstream of it, in Eastern Europe, which has failed. So, what more evidence does one want to show that things have failed?

POM. Would you like to see provisions regarding the structure of the economy written into the constitution? That the constitution would contain a commitment to a free enterprise system?

MB. Well, I don't know if that is a constitutional issue. But I wouldn't mind. If it is controversial, I wouldn't mind if it was determined. Because I have already said that, of course, there should be, Professor, a certain amount of distribution of wealth. Myself, I do have that proviso. But I don't mean that the government should override market forces. I've said that just as in Europe, there is a certain amount of that even in England, I would say as far as social programmes are concerned, where there are inequities, I think that those should be done from the common ... trust by the government. And, of course, in this country, there have been these disparities whether it's in education or whether it's in pensions. There has been a sliding disparity scale where things are always loaded against black people and I think we have to deal with those and I think one can deal with them through the common ... trust, you see, to reach new blacks who in the past who have had no access.

POM. What impact do you think the Communist Party has on the leadership of the ANC and the policies it adopts?

MB. Well, one must assume that, since they are partners, I think that Mr Slovo is a very prominent member of the National Executive of the ANC and he is also the General Secretary of the South African Communist Party and that, therefore, you've in the past, due to the fact that most of their hardware came from Russia and the Eastern block of countries, they must have a lot of influence. Because even the military wing was based on hardware that they got from communist countries. And so it must have a big say and quite a number of them are now both because there are members of ANC who are also members of the Executive of the South African Communist Party. But there are so many members of the South African Communist Party who are members of the National Executive of the ANC. So, it's clear that they must have a lot of influence on the ANC, the communists must have a lot of influence.

POM. What does, in your view, a member of the Communist Party believe that a member of the ANC doesn't believe? I mean, this whole concept of communism has become so nebulous since its collapse in Russia and Eastern Europe. Could you define what a South African communist is?

MB. Well, I think you'd better ask them, Professor, really. I am not a spokesman for them.

POM. But when you hear it, if I mention the phrase to you, what does it convey?

MB. What?

POM. If I mention the phrase?

MB. They do, for instance, they do believe in nationalisation, just as, the things that have failed in Russia, like nationalisation, they believe in them. Mr Slovo has said that, in fact, there is nothing wrong with the communism as such, but he says that it was the people inside that messed it up. That is why he says that, therefore, there is nothing wrong with the ideology itself. It was the way that it was handled. I don't know what more wisdom he has than Stalin and others that he hopes to display.

POM. For the average person who lives in a township or in a squatter camp, what difference would a majority rule government make to that person's life, tomorrow morning or even five years from now?

MB. Very little.

POM. Do you think out there there's a level of expectations has been created?

MB. I'm worried about the level of expectation, frankly, Professor. I'm very worried, myself, because there are many people who think that a new heaven is going to dawn as soon as black people are participating. But, in fact, the real struggle will start there. We will try to deal directly with most of the inequities of our society.

POM. When you look at your own community and look at this process, what do you see as the main obstacles or stumbling blocks that stand in the way of bringing it to a successful conclusion?

MB. Stumbling blocks to what?

POM. You have this process going, the negotiating process. Now looking at your own community, what are the obstacles?

MB. To what?

POM. To making that a successful process. What can derail the process? What can bring it to a halt?

MB. Violence can bring it to a premature halt. If some of the parties refuse to come to the table, because I believe that for it really to stick, then all parties must be represented.

POM. So, if the PAC, for example, did not come in?

MB. PAC, for example. In fact, I am talking to some of them because I'm more concerned about that.

POM. Let's talk about the youth for a moment. You have this generation ...

MB. Pardon?

POM. Let's talk about the youth. You have this generation and the post-1976 Soweto generation who are uneducated, unemployed, perhaps unemployable, who are used to only to a culture of confrontation and protest, and many of them are perhaps in support of the ANC and the armed struggle and now they don't know why the armed struggle has been abandoned. Two questions. One, do you think the PAC will serve as some kind of magnet to pick up disaffected youth?

MB. Yes, the newspapers have said so. As I said, Professor, I don't prophesy myself, but in many newspapers, I mean, many journalists have speculated in the media about that. They are saying that they are going to gain more, I don't know. They have said so.

POM. Well, what do you think must be done to bring the youth under control?

MB. Well, I think that we try here. You know, whereas the ANC said, "Liberation now, education later", in Inkatha, we said, "Education for liberation". As a result of that, I would say it's not really something worth boasting about, but I would mention as a fact that last year the ten top matriculants in the whole of South Africa, including the top, came from here because that's the way we are trying to orientate our youth.

POM. To go back to the armed struggle again. You gave an answer in an interview you did last week, after Mr Mandela did his interview, in which you were asked whether you believed that the armed struggle had, in fact, ceased. And, as I recall, your answer was, you don't believe that.

MB. I said that I didn't see, sir. I said that, in view of the undertaking that Mandela took, I would only believe that is true only when the violence that some of them unleash against my own people on the ground stops. I said so.

POM. Beyond the question of the sanctions and the use of violence, what other policy differences are there between the ANC and Inkatha?

MB. There are no others. I've said already, that our aims and objectives are the same.

POM. You also said in the course of that interview that the KwaZulu state didn't arise out of the homeland policies.

MB. Of course it didn't. I'm sure you know that. You know as the British rule broke, we were protected. We're a sovereign state, just like Lesotho and Swaziland, which are recognised by the United Nations as states. We are not a creation, a construct of the government's policy, unlike all of them. But we had already moved ourselves, since history has made us South Africans, we are moving, through the Buthelezi Commission and the Indaba, we are moving in the direction of having a non-racial state here within South Africa of everybody in Natal or KwaZulu, so that we could have on a federal basis, a consociational basis, we could have one sovereign state in which we participated as a non-racial state.

POM. To go back again for a moment to the economy. How much time do you have, by the way?

MB. I should really leave, because I'm in the middle of - we are discussing with the whole Assembly, this violence in Johannesburg. The whole Assembly's here in a caucus meeting. But I also heard that you had appointments with the King, as well. So, it takes a long time to get there if you are going now, to Nongoma. The roads are not good.

POM. The road's not good?

MB. No, it is really unpleasant. The King complains all the time.

POM. Just one last question. You have these huge imbalances between expenditures on blacks and whites.

MB. Quite. This is, in fact, you remember that, Professor, I said that one of the things that should be addressed are these disparities in pensions, and what is spent per ...

POM. What I'm asking is, where will the resources come from to eliminate these inequities, given that there is a very narrow tax base in the country and taxes are relatively high already?

MB. Well, I really don't know, but the point is that one must hook one's wagon to a star, isn't it? And as far as I'm concerned, I think this is what we should address, but I can't pontificate about whether we will be able to do it or not. Because quite clearly, we are a besieged economy in this country. And what is happening, the violence and so on, I don't think it's going to attract investors whether sanctions ended tomorrow or this afternoon. So, I realise that there are problems.

POM. OK. Leave it at that.

MB. I'm happy to have helped.

POM. Thanks. I'll send you on a transcript of this in due course and I hope that I will be able to, perhaps, do interviews at least once a year with you over the next four, five, or six years.

PK. Dr. Silber ...

POM. Yes, John Silber sends his best regards.

PK. John Silber and ...

POM. Two people did. Jim Thompson.

MB. You know him?

POM. Oh, yes.

PK. Very well.

POM. And Jim Thompson, who used to be the ...

MB. Oh, yes, he's a very good friend of mine.

POM. Former curator, yes. Jim did an historical ...

MB. And his wife, too.

POM. So, they both said to say hello.

MB. Give them my love, please, Professor. They are really lovely people, all of them. And John Silber, I heard, was standing now for governor.

POM. Yes, he's learning what politics is all about now. It is a lot more difficult, I think, than academics. You've got to watch what you say, that's what he's learned.

MB. I don't know, Professor, maybe I am loading you, but while you're in South Africa, you could perhaps, since you are interested in conflict, read some of these things. Because everyone is mystified, are surprised, when I say I talk to the State President and to other people. I delivered a letter to Mandela last week, which I still emphasise. I must give you, also, my memorandum of yesterday.

PK. Oh, yes.

POM. Yes.

MB. It was in that I set out the dates, the strict dates on which I asked to talk with Mandela, apart from the dates he asked me. But some dates I gave him to which he has not honoured yet. And to everyone he says that. You know, I've never attacked him, but I attack the ANC. But if you could see the vicious campaign of ANC against me, really, you really will ...

POM. We've seen some of it, and I suppose that's what I was trying to ask you. Why do you think it has become so vicious? I mean, for many years, you said you would not enter into negotiations until Mandela was released. You stood up for him at a time few other people were. So I suppose what intrigues me, how has it become so vicious?

MB. No, but as I said, Professor, he said himself he was almost throttled. In fact now, when I said on the talk show, I said he's a captive today more than he was in prison.

POM. Yes. Do you think that was ...?

MB. And many people say that he is really not in control, you see. And it's obvious that he is not.

PK. What do you understand, though, makes up that character, that he can allow others to control him in that way? Is it his strength? What is his personal strength?

MB. I would say, myself, that if one has been in jail for twenty-seven years, I don't know what happens when you have not been able to organise. And now you've got this other case, like COSATU, who will talk to you by saying that, We will support you provided you toe the line. I read this as a drastic situation where they have erased competition, where they have acknowledged the knot between ANC and the South African Communist Party. And I think COSATU, for instance, wants to call themselves the South Africa Communist Party, really. So, Mandela is in a glass cage, I think, but he doesn't forfeit, whereas only now that ANC could really be in a position to organise and so on.

PK. And what does this say to you about his leadership capabilities for a nation?

MB. Well, really, I did at one point - you see, we politicians, as you know, can look over our shoulders to hold our constituents' support. But at the same time, I think a leader should lead from the front as well.

POM. How would you assess his performance after six months, if you had to grade him?

MB. Well, I must say that, you know - in fact, I look foolish to many people because I think I overrated him because when I was backing his release, when I talked, I said, I know this man is my friend, which is true, he was a friend of mine. He knew my wife and little girl and so on and I know he is a great man. I used to have dinner in his house. I know him as a person, he is not a legend to me. And I said that he would be a force for reconciliation, not only between black and white but between black and black. But this has not happened. I mean, he has surprised me in some of the outbursts, in spite of the hype in the United States and everywhere. But, I mean, he has contradicted himself and so on precisely because of the position you have just portrayed of him being in a glass cage.

POM. So, do you think, again, in the community, that there is a kind of disappointment with his performance? That he hasn't proven to be this reconciler that people thought he would be?

MB. Yes, I mean, they thought he had a magic wand, which, of course, I wouldn't say I expected him to have myself. But I did expect that he would be more effective than he has been. But unfortunately, this has not happened. This has not happened yet. And he hasn't shown any strength in controlling. Because he says it often, even to Mr de Klerk, when we talked privately with Mr de Klerk he told me that he told him that it was the others who are against it whereas De Klerk was emphasising to him the importance of us getting together. Even the three of us, if possible.

POM. Do you see this stranglehold on him continuing and if does, that it really means that there can't be peace, or do you think that in the end ...?

MB. I'm very worried about it, Professor. Honestly, I'm very worried. Because it may well continue. I don't know.

POM. And if it continues, the violence?

MB. I mean, then we are in square one, really we're back in square one at the time where there are so many hopes that were moving. I'm very worried. I'm very concerned about it.

POM. All right. Thank you very much for your time. We know you're very, very busy.

MB. Thank you. I'm glad this worked out.

POM. We definitely appreciate it.

MB. I'm very worried about it.

POM. We'll be back again.

MB. Thanks. You're welcome.

PK. Hopefully there will be peace.

MB. I really hope so, really. I also hope so. Should I get this memorandum for you?

POM. Yes.