This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

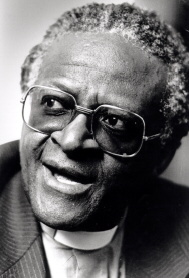

24 Nov 1995: Tutu, Desmond

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. It's a free country. Maybe that's a good place to start. Let me ask you, this is a theme that has occurred in some of your speeches in the past over the years, and that is when can people as a whole stop blaming everything that is wrong in the country on apartheid or the legacy of apartheid?

DT. In a way almost immediately and in another way never because let me say that we need to be careful that we don't as it were hamstring ourselves by constantly looking for scapegoats when we should very earnestly be taking our lives in our own hands and determining our own destiny; and that it is very debilitating constantly to be harping on the victim syndrome. But there is another sense in which it is important that we do not in a sense hamstring ourselves in a different way, be overwhelmed as it were by maybe our own inadequacy in the face of problems because we do have to acknowledge that many, many of our problems are the legacy of apartheid. You take education which has repercussions in all kinds of areas. If you say, but why don't we have enough blacks in this that and the other area, and you say it was because apartheid deliberately held people back; why do we have this massive backlog in housing, etc., etc., etc., it is important that we do identify the causes properly so that we can then also properly look for the right remedy.

POM. If you look at something like the culture of non-payment for services where the Masakhane campaign got off to a good start and then it floundered, where there still doesn't seem to be recognition among people that if they don't pay for services the services will not be delivered and if they don't pay the bonds on their houses there are going to be no houses built for the millions of people without houses. What has been failed to get across to them?

DT. I don't know that we have failed. Many realise that you have to invest something in order to get a dividend but we are having to deal with quite a number of things. You have people who are making the very serious mistake of thinking that freedom means license to do whatever you like and from doing whatever you like you can claim whatever you like in a way and so we are having to combat the culture which is the culture of entitlement, that somehow people also don't make the connection that you can have a right but if there are no resources to turn that right into actuality it's not particularly useful. Some people are saying that the constitution or the bill of rights must ensure that social rights like having a house should be enshrined in the bill of rights. Now I said I understand that though I am worried that many people will not say this is to say that everybody deserves adequate accommodation, but that they will move from that and say if I have a right to a home, a decent home, then somebody must deliver that home and then they make the claim, and I am not yet entirely persuaded about this.

. But, too, you see there is a whole thing about mindset. I have been saying about myself, for instance, that it is a good thing that I am stepping down now as Archbishop because my leadership has been a leadership of 'against' so we have been in the 'against' mode and now we want a paradigm shift, a mindset shift to the 'for' mode. Even if I stand up and I say that the against-ness was a preliminary to prepare the way for the for-ness I think, not just in South Africa but perhaps everywhere else in the world, I could say that in a sense I was a kind of icon of the against-ness and when people maybe see me they would say, yes he was there speaking when the other people were not there and speaking against. And it's a very difficult thing I think to change mindsets.

POM. Someone was telling me that one of the areas in which there never was a boycott was on trains, on paying train fares, and yet they estimate that one in every two people simply hop over the stiles and walk on to the trains and don't pay. So my question would be, what kind of vision has not yet been given to the people that they need to understand that unless they pull together and row together nothing much is going to change?

DT. Well I think we have just to go slogging and reminding people that the non-paying strategy was a strategy for the struggle against apartheid. Now that struggle has succeeded and our strategies must now change, our attitudes must change. We had an authority that was not a legitimate authority. Now the authority that demands these things is a legitimate authority that needs to be supported and you're just going to have to struggle to try and get people recognising this. You know, I think when you come out of a situation of deprivation and you live in a country where the changes are not too apparent in a way, the changes at the grassroots, as they say, we have democracy, that is OK, we have a government which we elected but we are still living in the shacks and the people who were the privileged in the old dispensation are still the privileged in this dispensation and people, maybe they don't articulate it, but some of their behaviour is behaviour that says perhaps, although maybe they would even say in theory there has been that change, as it affects me there has not really been a great deal of change, I still live in a township, I still have to struggle to get to my place of work and I still basically am working for those who belonged to the privileged group in the previous dispensation and so even if the authority says it has changed my experience, my existential experience is much the same. And it doesn't help, people may not say a great deal about this, hardly anything at all, it doesn't help to see that certain people have made it and have made it in a blatant way. There's a gravy train situation. Although there is not yet a deep resentment or even maybe a disillusionment there may be a creeping kind of cynicism that in fact what seems to have changed is just the skin colour of those who are privileged.

POM. I want to go back to the gravy train in a couple of minutes but first of all I want to take you up on the question of legitimate authority and relate that to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission. Just personally I have been trying to wrangle with the incredibly formidable problems that this commission will face and the kinds of questions it would have to ask itself and are being asked of potential members of the commission now. But do you make a distinction between a crime committed against an illegitimate authority that is an oppressive, brutal regime which is denying people their freedom, where those freedom people are denied any manner in which to express themselves politically and that their only recourse is through the violence which is likely the course of last resort, do you differentiate between a crime or a murder committed against a member of that state or for the liberation of the people, distinguish it from a crime ordered by the illegitimate state in defence of itself and of its own interests? So is murder always murder or are there distinguishable degrees of what might be called more morally, I hate to use the word, morally correct, morally acceptable?

DT. Well of course that is the distinction that has always been made, the kind of decision that you make for beginning to accept that war can be acceptable. So the classic thing is if a woman is about to be raped and she uses force, even kills the potential rapist or the person who may in fact have got to raping her, and the murder of someone because they had money or when somebody wanted to hijack your car and they shot you and killed you, the moral quality of those two acts of violence are regarded as being different. The woman in a court of law almost certainly would be acquitted as having engaged in justifiable homicide whereas this other one would be something that was condemned. But the legislation in fact does not itself make a distinction. It says that those who are applying for amnesty, for any actions including murders and things of that kind, they have to satisfy criteria. There will be a committee of the commission that deals with amnesty headed up by a judge and I think it has a judge as a vice-chairman as well. The criteria that are used are: was this an act or an omission to act in a particular way in pursuance of a political objective which was part of the policy of a political group, either that group could be a state, the state, South African state, in defence of its policies or it was an act or an omission to act on the part of a liberation group in its opposition to apartheid? If those criteria are met and the particular occurrence took place between set dates then the morality of it is not in debate. If it was an act by a government agent in pursuance of that particular policy the amnesty would have to be granted. If it was an act by a member of a liberation movement in the struggle

POM. Let me give you maybe an example that always comes to my mind because it's used, is that if I, say, set a car bomb off some place, which has been used by liberation movements all over the world, and ten or twelve innocent people are killed and the policy of my organisation is to have car bombs go off in order to render the state ungovernable, slowly to bring it to its knees, and innocent people get killed, is that morally equivalent to that if I am a general in the state apparatus and I say I want the following four people liquidated, eliminated, whatever (was it Henry II who said, 'Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?' when talking about Thomas A'Beckett), and I'm doing it in pursuance not of the policies per se of apartheid but believing that they are part of the total onslaught of communism, Godless communism? Do they become morally - ?

DT. We would have to debate the moral equivalents that you might want to see between them but the answer that I gave you about the woman being raped and somebody killing because of wanting to hijack a car indicates that morally I would myself say that the action, the action of a liberation movement operative is at a different level to that of someone who was supporting an unjust dispensation. But as I say, in terms of the operation of the Truth Commission, so far as I am able to understand the legislation, the morality doesn't come into question at all, it is just that was it for a political motive during the time of either upholding or struggling against apartheid and was it the policy on the one hand of the state or on the other a policy of a liberation movement? And if the answer is in the affirmative and, third, if it occurs within the time frame set, then you don't spent time discussing whether it was morally acceptable or reprehensible.

POM. Is there a form of double jeopardy here? I go before the commission, I admit to a certain number of crimes, I say that I did them in accordance with my political principles to achieve a political goal; the committee reviews the evidence and circumstances and says, "No we have decided that in fact you did not." Now I have already admitted to something so I am now going to be tried before a court - or am I going to be prosecuted where already I have admitted my guilt in the belief that I was going to get amnesty?

DT. I can't recall quite although I know that there is, I think there is a provision, that evidence that has come before the Truth Commission may not subsequently be used to incriminate whoever. I think the aim of this particular legislation is in fact to encourage people to come forward to make the full disclosure because that is actually the other condition that disclosure must not be a partial disclosure, it must be a full disclosure. And I think the ultimate purpose is that the truth should be known and one hopes, of course, that there will be mechanisms in society which are going to help people handle the truth when it gets to be known, and, of course, the thrust of the legislation is basically towards the rehabilitation of the victims, the survivors, the re-assertion of their human dignity and where appropriate restitution of some sort would be granted to those who were victims rather than engaging in a witch-hunt to expose. That may happen. Despite what I have said the legislation also seems to provide for the establishment of an investigative unit of the commission. I suppose it might very well be that if, for instance, someone who was a victim says this and this and this happened and there is no immediately available corroborative evidence, that this investigating unit would probably then seek to establish the veracity or otherwise of the allegation made by this particular person.

POM. Isn't it a great temptation on the part of some people to make allegations against superiors simply to exonerate themselves on the one hand and very often because of maybe some kind of revenge motive that they have been tossed to the dogs?

DT. The risk obviously exists but one has to remember what happened in Nuremberg, the upshot of Nuremberg in one sense was that obeying an instruction or a command by a legitimate authority was not in itself sufficient excuse that legally would exonerate the person who had carried out that instruction. It's quite interesting, it's also interesting that they got to the point where they were saying something like ignorance of the law is no excuse.

POM. But this kind of comes in conflict in a way with the guidelines that if the act was committed in connection with a political motive and if the subordinate was in fact carrying out the command of the superior because the superior was acting according to a

DT. I have said that the parameters for an amnesty are set by those particular conditions that I have indicated. But I am just saying that it would not necessarily be an excuse for your own moral responsibility. I think again that the thrust is not so much in a way to unearth guilty parties as to say what do we do with those who were clobbered by the system. How do we help in their rehabilitation, in their re-integration into society? What do we do to help to restore a dignity that was undermined by the actions or lack of actions of, say, the Nazis?

POM. Would you see necklacings coming under this category of politically motivated crimes?

DT. I think you've got to look - I found them myself particularly repulsive and I said so at the time. They are actions that were taken, you will have to say, was this in line with the policy of a liberation movement? It's not enough just for the person to say, I had a political motive. Well the legislation says that you have to have been consistent with the policies of one or other of the organisations, either the liberation movement or the state.

POM. But if you're a kid and the instruction is that it's your patriotic duty to make the township ungovernable and break it and part of doing that is keeping people in line, making sure boycotts are observed, making sure there is discipline, you have to have instruments of fear and intimidation to make these things work.

DT. We would have to ask the political organisations, was this your policy? You have got to find out was this your policy that amongst other instruments of intimidation - I mean did you use intimidation, was it part of your policy to use intimidation? If yes did you sanction the use of necklacing and other ways of liquidating collaborators? Was it part of your policy? And they have to say, and I don't know, they might say yes broadly their policy was to make the things ungovernable. I don't remember, I am not aware that during the time when it all was happening that any political organisation, so far as I can make out, admitted that this was one way that they accepted as policy.

POM. But it's the sin of omission by saying nothing.

DT. But you see it's got to be clear that this was policy. I think this is one of the criteria because you could have had aberrations that were committed by people who might say that I am ANC or PAC or whatever and do things that the political organisation would repudiate and we've got to go by - well I think the commission would have to go by what the political organisation, the liberation movement itself declared.

POM. But if I am 16, 17 years of age, I haven't gone to school and I live in a tough, brutal environment and there's somebody out there called the oppressor and there are people in my community who I and others with me regard as being collaborators and we think that the political organisation with which we are aligned, which is mainly outside of the country, we think that they would approve of us enforcing this kind of intimidation. I'm not trying to put you on the spot, I'm trying to get answers for myself.

DT. Well you will have to go and ask the chairperson whoever he may be of the

POM. That's what I'm doing.

DT. No, of the committee that is going to look at the applications for amnesty and I believe one of the reasons why they are going to have at least two judges serving on this is that you are going to have to sift all kinds of evidence which a lay person such as myself would not be always too competent to do. But what I know is that they would be - well the legislation seems to be quite clear about the particular attributes that are to be found in an action or an omission for that particular action to come under the rubric of amnesty.

POM. Now the spokesman for the National Party said at the time of the arrest of General Malan and I quote, he said: "There is an understandable swelling of rage in National Party circles because a different set of rules is being applied to the previous government and to ANC leaders." Given the fact that a number of the top ANC leaders and PAC leaders and others were given temporary indemnity back in 1991 and that there is not in itself any reason that they ought to go before a Truth Commission, or any commission, to be indemnified since they already have been indemnified against all their actions, is there not a different set of rules? How do you level the playing field there?

DT. The distinction seems to be quite clear. There are two things, one is that the ANC people admitted to having participated in certain actions so that there is a disclosure that they made which qualified them for the amnesty or the indemnity. They said we were part of a liberation movement that carried out certain actions and we accept responsibility for having been part of that and, yes, we apply for this. Now the generals haven't done so and some of them would say that they don't believe they need to come before the Truth Commission to apply for amnesty, so you don't grant the amnesty, as it were, automatically without application. That is one.

. The second, which I think is the point that the President is trying to make, apart from the hesitancy of the executive interfering in the judiciary many people are saying, and the Sunday Times Editor was saying, "Well the generals have a wonderful opportunity of demonstrating their innocence and it is particularly crucial that the executive does not interfere. Let the trial be a free and fair trial in open court where they are presumed to be innocent until they are proven guilty" The government had no say (that is what they are saying), they had no say on the decision of the Attorney General of KwaZulu/Natal to arraign these people. It was an action that was taken after a special investigating unit had collected what it believed to be prima facie evidence and the President indicated to us that this particular task force had included, I think in its membership or in the membership of those who review the evidence, I think two or three people from overseas who are experts in the kind field, in police work and so forth. But the other is that the Attorney General seems, indeed made the decision as an independent judicial officer.

POM. Weeks before that the ANC were castigating him from above. Just to go back, my understanding, and correct me if I'm wrong because I've asked a couple of people and I get conflicting replies, is that when the ANC members from overseas had to apply for indemnity first they had to list the actions for which they sought indemnity and if they didn't list an action and they entered the country and it was subsequently found that they were involved in something else they could be prosecuted against that, and that by and large they refused to do so and that some general formula was worked out where they agreed to admitting any actions against the regime which resulted in damage and death and injury to people. But it was vague, no-one admitted to specific charges. If the same criteria is applied, if that's true and the same criteria is applied to people in the state security apparatus they could end up making bland statements like, yes I participated in ordering the murder of a number of people in order to safeguard the interests of the state, blah, blah, blah, but I'm not admitting to any

DT. Any particular. I don't know, I can't be, well maybe I shouldn't have said expected, I don't know all the details but I think the major difference is still that these chaps on the one side have said, "Yes we've done this." These guys on this side I think are just saying, "We are innocent." General Malan has said he doesn't want any political interference. He wants the trial to go on because he knows he's innocent.

POM. I was talking to people the other day in Thokoza, a number of families out there that I regularly go out and visit, and we were talking about the results of the local elections and I went through a list; I said could you ever vote for the National Party, and the answer was unequivocally no. Could you vote for the IFP? The answer was no. Could you vote for the PAC? Well maybe but they are so small they are marginal. Then who could you vote for? Well, the ANC. Three years from now if the ANC has delivered nothing or very little and it comes to a new election what will you do? And they all said well I either vote for the ANC or I'll stay at home. In a way that's a situation that makes the political system very close to being a one-party state, that people are going to vote along racial lines for a long time to come and that if the National Party believes that some miracle is going to happen where they are going to start drawing large numbers of black voters then they seriously misunderstand what they did in the past or have no knowledge of the history of what they did, would you think?

DT. Yes, I would still want to say though that it's been interesting, I mean two things have been interesting particularly, that the ANC should have won in places like Ventersdorp. Ventersdorp now is

POM. That the ANC should have won?

DT. That it should have won. I mean it won there. That is an extraordinary thing. Now that is the headquarters, that is where Terre'Blanche is and you would have thought that if there were going to be any possibilities of the right wing holding on to support it would be in places like that. And to have won so convincingly in places like the Orange Free State seems to me to be saying that whilst of course it's fundamental base support is black it's not entirely black. It is still one of the extraordinary things of this country that they have in the ANC a Verwoerd sitting in parliament, the granddaughter-in-law of Verwoerd. Now you might say it's one in how many, I don't know, but the fact of the matter is that that has happened, that the appeal of this party seems to be one that spills over what you might have called traditional ethnic bounds.

. Then the other is what has in fact happened to the right wing. You would have thought that they were on to a good thing, they did have very, very emotive subjects. The crime rate. I mean the crime rate alone ought to have won the Nationalists and the right wing, that they could have said just look at what happens when you have a black led government, you can't live in peace, you live in a virtual prison in your own house. Pretoria, the Conservative Party which had virtually all the seats in the Pretoria City Council lost all of them. Even the Freedom Front, it's peculiar because you would have said in those places at the very least they should have had a reasonable showing but they didn't.

POM. But if you look, I think, at the figures you will see that the conservative votes went to the National Party and that the Coloured votes that the National Party had in areas outside of the Cape went to the ANC so that despite its efforts to becoming a more multi-racial party one of the results of this election is that the NP is more of a white party than it was before 1994.

DT. Yes. That might be the case. What I myself am trying to indicate is that if you are saying we are moving in the direction of a single party democracy, which I would hate to see happen, the thing is that the ANC's appeal, it appears to be an appeal that is not confined to black people. I think they are beginning to get white people seeing it as a party that they might be willing to support. It's as crazy as a thing that now - have you met anybody who ever supported apartheid?

POM. Not even the people who did. Of course they did, yes.

DT. Virtually everybody is finding a deep embarrassment actually to admit that they supported apartheid. Everyone has some wonderful reason why they were where they were but they were always very nice to blacks and they were brought up very nicely.

POM. Just a couple of last questions for you because I know you're pushed for time.

DT. You've got only two more minutes. Come on you do your worst.

POM. Compromise, three and a half. Consensus.

DT. Yes.

POM. OK. One is on crime. I've heard you talk before about ubuntu, kind of the spirituality of South Africans and their gentleness and how they don't bear grudges despite the awful things that have been done to them in the past. Yet with the crime, to me it's not so much the level of crime it's the brutality that has become associated with it in terms of whether it's murder, the randomness of it, it just like rather than open the door and pull somebody out of a car, just shoot them, pull their body out, it's just quicker, but it's rape, aggravated assault. What do you think accounts for that in view of what you would see this gentleness and this Christianity and this innate forgiveness of the South African?

DT. Well very many things. We are in a period of transition and there is always instability. You see it in your Eastern Europe, your value systems are turned topsy-turvy in those periods of transition. That is one sort of general explanation. The second is that in times when your economy is not performing quite as well as it should (although it's not doing badly, the inflation rate has dropped very, very considerably) but we still have a very high level of unemployment and when people are hungry and when people are unemployed then social dislocation happens almost by definition. And then of course we have got to keep being careful about speaking about the brutalities and lack of humaneness. Here we have got the worst trial in England, discovering that a man and a woman could do that, two people to kill their own children even, and if you want to, you say what's happened to those kids who took that child, again in England, on the railway line and smashed up the child just almost for kicks. What's happened there because you have a more normal society and when you look at the crime rates in all of those places you are saying - the thing is it's very small comfort obviously for me to be able to say I can point to almost even worse things. How do the Oklahoma's happen in societies that have claimed to be more civilised, more developed, have been free a great deal longer?

. We should ourselves be working for the re-establishment of our values, our value system, and it's an uphill struggle because apartheid had actually left us wounded, all of us traumatised and has brutalised people because they saw many things that shouldn't have been the case. We used to say they learned with the old government that when somebody disagreed with you, you didn't tolerate that disagreement, you didn't even try to persuade that person to change that point of view; you either put them in jail, you detained them or you used your death squads against them. Now whether you are saying to people, this is what you must learn, this is how you do it, or you just leave it to them, they absorb it as being part of the milieu in which they move and we in countering apartheid are going to have to be trying to recover, help people recover their humanity, their ubuntu.

POM. Last question. Is there a gravy train?

DT. Oh yes, I think there is.

POM. When politicians, again black politicians, say this is part of a conspiracy on the part of the white media to again portray Africans as corrupt and this and that and the other, is there a measure of truth in that or are the two true?

DT. I think there has got to be an honesty. The honesty is, of course, that there are gravy trains and gravy trains. I mean there's a gravy train in the private sector where some of the pay that these people have voted themselves, some of the directors, I think is almost an obscenity. We should be saying that all of us in this country need to be looking again at our value system.

POM. Is it something that the government should be more aware of than it appears to be?

DT. Oh yes, I think they listened a little bit. But you see all of us being human have a resentment when we are told that this is not quite right. All of us react initially by getting angry, but I think those who are more earnest are aware that there are some things that we should not take on board, we should jettison.

POM. Thank you ever so much.