This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

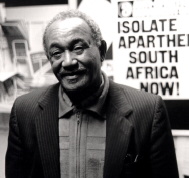

21 Aug 1990: Gumede, Archie

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. We're talking with Mr. Gumede on the 21st of August. I recall when we talked the last time you had said that you were going to try to get Mr. Mandela and Mr. Buthelezi to meet. That was about three weeks ago and things have gotten a lot worse since then and still no meeting has taken place. What do you think is going on? What is the meaning of the spread of the violence out of the Natal into the Transvaal?

AG. Well, candidly, the nationalisation by the Mass Democratic Front of the call for the end of violence, through the government taking, removing the police from KwaZulu and dismantling the KwaZulu government, things of that kind, would appear to be somewhat likely to have negative consequences and these are the negative consequences now. Although, perhaps, others may differ with me in my interpretation of the sequence of events.

POM. Oscar Dhlomo, the former Secretary General of Inkatha, warned about the dangers of trying to ethnicise differences between blacks, that this could have a very bad effect on the whole South African situation. Do you think the differences between ANC, UDF, COSATU, and Inkatha have now developed an ethnic flavour that is becoming more of a Zulu versus Xhosa?

AG. No. The possibility of the conflict deteriorating to that extent, I cannot rule out. Buthelezi has stated that the action is an attack on the Zulu nation. And, of course, it so happens that the Central Executive of the African National Congress, the leaders of the African National Congress, comprise mainly Xhosa speaking people. I think there is a man name Zuma and another named Maduna who are not really - Zuma is a National Executive member and Maduna is a Zulu and Maduna is in the Legal Department. Well, it's not difficult, then, for Buthelezi to portray the African National Congress as an organisation that is led by Xhosas.

POM. And, of course, for Zulus living in these hostels, things will always be reduced to a very simple level, anyway.

AG. A very simple level.

POM. Why do you think Mr. Mandela will not meet with Mr. Buthelezi? Here is a man who when he came out of prison preached the need for negotiation. I mean, even in London said that Mrs. Thatcher should talk with the IRA, that everybody should negotiate with each other, and yet the violence mounts and the ANC seems to be resisting any attempt to bring a meeting with Mr. Buthelezi and Mr. Mandela about.

AG. Well, I would say that that's reasonably a conflict of their engagement and a representative from many of the organisations that are involved with the Mass Democratic Movement took part in the discussion. I was not present when the actual discussions took place but I was present when there was input by people like Harry Gwala, Jay Naidoo, and some other persons and those were apparently motivating for ostracising KwaZulu government, I mean, Buthelezi and Inkatha. What took place when the discussions were held, I don't know. But I believe that the impression that Mandela was given was that it would be, as Walter Sisulu said last night, it would be disastrous to give way to the use of violence for political aim.

POM. So they are really seeing the violence as being instigated by Inkatha, trying to force talks with Mr. Mandela, and then claiming political credibility, or political importance, as a result of those talks?

AG. Apparently that is the perception of those who are advising Mandela in this regard.

POM. What do you think yourself? What do you think ought to be done at this point? What would you advise Mr. Mandela to do?

AG. Well, you know, looking at the images of these two people, I see, well, a very big figure in Mandela and not so big a figure in Buthelezi. Well, let us look at the reception that Buthelezi received in America and the attention Mandela received in America and Europe and so forth, and then you see what I am trying to convey to you. When you look at those two I don't see that there is anything that can dent Mandela's image to talk with, or that would likely to enhance Buthelezi's image, to his having had a discussion with Mandela. He would have to produce good reasons for not agreeing to the end of violence in this situation.

POM. Do you not think if there is ...?

AG. You couldn't put, for instance, say, 'Well, if you don't give me a position in your government, then I'm not going to.' He couldn't say that.

POM. Do you think it is a dangerous strategy for elements within the ANC to say let's isolate Buthelezi, let's try to cut him out of the process?

AG. Very dangerous, very dangerous. Now, perhaps those people may not suffer the consequences. But if people are not careful and the perception develops that it is a Xhosa and Zulu conflict, then the Xhosas who are in a minority in Natal would be in very real jeopardy. I know there are police. I know there is an army, but you can't get the police and the army everywhere. And when people are up to their own thing then the police only come after damage has been done.

POM. But do you think that Mr. Buthelezi, too, must be made part of the solution? You know, that you can't bring a peaceful settlement ...

AG. How can you, how can that be done? I mean, you see, I grant you that a captain of one team can give orders to members of another team or the players of another team. Is it possible? Now, I have never seen it done. I don't think that while there is this rivalry between this one sect and the other, people of the other man, they say, 'No, this man wants us to be placed in a weaker position than himself, and that is the end of it.' Who is going to - I mean, could Mandela, could Buthelezi come and tell the comrades not to do these things? Or can Mandela go to Gatsha Buthelezi and say, 'Now please don't carry your weapons.' I mean, I don't see that it is possible, but I do think it is possible for Buthelezi to tell his followers not to do this and for Mandela to tell his followers not to do it. I mean, there is no doubt that the two of them are the leaders of these two organisations and that these two organisations are daggers drawn. I mean, nobody doubts that.

POM. If this continues will it be possible to have meaningful negotiations?

AG. There's no meaningful future, not meaningful negotiations.

POM. I'll come back to this in a little bit but I wanted to get back for a minute to February 2nd and Mr. de Klerk's speech. Were you surprised by what he had to say and what do you think motivated him to move so broadly and so sweepingly at the same time?

AG. Well, looking as I did at the events as they unfolded, it was apparent to me that the continuation of the situation as it was prior to February 2nd was untenable. In fact, I rather think that the amount of thought to be applied to that problem must have been tremendous because the reality of the matter was simply that there would be chaos developing from day to day.

POM. The country had become ungovernable.

AG. Well, in a sense it had become ungovernable in that, in fact, it was on the verge of ungovernability in the sense that the economy was in a very bad way and the security forces were at their wit's ends, too. How to bring order, because less and less respect was being paid to their orders and instructions.

POM. Do you think that Mr. de Klerk has conceded on the issue of majority rule?

AG. Well, I don't see how he can re-establish minority rule.

POM. I mean in a sense of he could give everyone, like that, do you think he is at the point, do you think he has accepted, say, black majority rule or do you think he is looking for some kind of an arrangement where the National Party might share power with a larger party, where power would be on a proportional basis? It would still be majority.

AG. No, I think that Mr. de Klerk has accepted that without the willing co-operation of the people, all the people of South Africa, no system would work. So if it comes to having a black majority, I think he will go with it, if that is the only way in which the nation will survive as a nation.

POM. What do you see happening yourself? How do you see the process unfolding? Now that the obstacles of negotiations are just about out of the way, what do you see happening? What are the various stages?

AG. Oh, that is a very difficult question to answer because you do have statements such as that made by Mr. Harry Gwala, have statements made by Winnie Mandela, have statements made by Chris Hani, and I just don't know. Now the indemnity has been rescinded. Mac Maharaj resigned.

POM. Mac Maharaj resigned?

AG. No, the indemnity has been rescinded. You see? So it looks as if part of the obstacles are not completely removed. Now, that being the case, I am not sure that the thinking of the ANC and the thinking of the Nationalist Party do really find one another in the sense that now there is appreciation of how the other will act when a certain act is committed.

POM. You don't think there is an appreciation of that yet?

AG. Well, the appreciation I don't think has been sufficient for one to really to say categorically that this is what is going to happen, this is not going to happen.

POM. But do you see, like, there are three scenarios that are kind of sometimes painted. One is there would be a Constitutional Assembly. The other is a broad negotiating table where all the political interests are represented. And the third is like a combination of an interim government where Mr. de Klerk would bring members of the ANC into his government and alongside with that you would have a body sitting, drawing up the principles of a new constitution. Which scenario do you think is the more likely one to develop?

AG. Well, the last one I do not think will satisfy the demands of the people. I don't mind what the white electorate feels about its rights because had that Parliament the power of veto, then we can just forget about it, any talk about the new constitution. There can't be a new constitution if that section has got the right to veto.

POM. Well, Mr. de Klerk has given a promise to the white electorate that he will take any new dispensation back to them for approval. Is that a promise he can keep?

AG. You wonder, with the changing circumstances, is it possible to make a future constitution dependent on the veto.

POM. The veto of one section of the country.

AG. Of one section, which has such a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

POM. Do you think white people are accepting the fact that in the not too distant future the country will be run perhaps by the ANC as the governing party? Or a party that is essentially black?

AG. Yes, well, I will say that the opinion formers in the white community, the people who are really applying their minds to changing circumstances, do accept that. Then you have the fanatic who will not accept that possession of a white skin is no guarantee that there can be a change in roles in society. There are those who are convinced that the country was discovered by them and it was in the same way that it was the promised land of kings, but of course now they don't tell us who their Abraham was, who their Moses was, just about Van Riebeeck and so forth, when they were in contact with God to tell them that the land that was coming to their grandfathers, who their ancestors were who received this promise and when. You see, they actually believe it is God's will. But of course, you see, it is only God's will when, in regard to owning land. [Oh, well, other things...]

POM. Do you take the threat of the right wing seriously? Do you think they are a real threat to the process or do you think they are, that that kind of reaction was to be expected from a faction of the white community anyway?

AG. Well, what I'm worried about is that they have the capacity to do a lot of harm to society. And I'm just hoping in their own self-interest they will realise that they are cutting their own throats when they act in that way. You see, there is a very big difference between Palestine and South Africa.

POM. Very big.

AG. Very big! You wonder if they equate themselves as Palestine.

POM. Related to that, we hear a lot about white fears. What do you think about whites fears? And can you break down their fears into fears that might have a basis for them and fears that are perfectly imaginary?

AG. Well, I don't think that they are imaginary seeing that there have been instances of gross cruelty on the part of white people to black people in many respects. However, the only way in which the ground for that fear can be destroyed is by the white people themselves exhibiting and showing that they are part and parcel of the South African community and that they live for the community and not for some foreign country. But everything of theirs, they are going to save the country as a whole, as members of the country.

POM. But, I'm getting back to, what do they fear? What are they afraid of? What are they afraid of in terms of there being black majority rule?

AG. Well, of course, I think that they are afraid that they are going to be victims of physical abuse. For instance, you see there have been cases of the farmers, the isolated people, now you see the press is publishing stories of robberies and other things and attacks on ordinary people on farms and so forth. There is that type of role. I think that they feel that the government in power may not sympathise with them to the point that they will want to punish people who have behaved in that way in respect to these white people. That's the only thing I can be able to see. But, as I say, if they become part and parcel of the life of the nation then they there can be no basis for fear because they will have been accepted, accepted without reservation.

POM. In that regard, though, what effect do you think the events of last week, the violence in all the townships, what kind of impact do you think that will have on the average white person?

AG. Yes, it may have a very negative impact on and create the impression that the black people are not emotionally and mentally attuned to living in a society where conflict is unavoidable. That may be the impression they are going to have. The real concern is do they look at how this has come about? Do they see the policies of the Nationalists in emphasising differences and creating the impression that things are irreconcilable and therefore that people in different ethnic relationships cannot live together unless they are separated? You see? So that these have had the effect on the black people, as far as I'm concerned, of creating those mistrusts and then, of course, the fact that the oppression of the black people has been physical. Well, that may be disputed but the fact of the jails and the police and the army and all those forces of security, state security, has created an impression that might is right. So people then come out accepting that for security you must have might and you must show that might. You must get people to feel insecure in your presence so that they will do your bidding.

POM. But, do you think the last week in particular will drive many whites towards the Conservative Party, make them more reluctant or unwilling to accept the inevitability of majority rule?

AG. Yes, well, of course, that is the something that causes worries because by doing that they are not making it easy to adjust for the future. I will say that to many the remedy will appear to be to run. No, no, no, because when, as a matter of fact, that the sooner we are able to get over this stage the better. One thing that we are always somewhat leery of forgetting is that history has many instances where people have had these conflicts in their community, Russia had the white Russians, etc., etc., and China, you had now Taiwan and the old Chinese, but that doesn't mean that they are not able to eventually be together in harmony wherever they are. So with this type of situation, I don't think that to the people who do really apply their minds to problems of this kind it will not be possible to persuade others that it is in their interest that they should set an example of the manner in which people are forced to behave in society.

POM. Some people that we have talked to have said that de Klerk's moves on February 2nd has exposed divisions within the liberation movement itself. Is that your experience? Do you think it has exposed divisions or that it is as cohesive as it ever was?

AG. No, I don't think that you could say that there were divisions but I will say that there are differences of opinion and I think it is healthy that there should be differences of opinion.

POM. Differences of opinion, like?

AG. Emphasis. I mean, for instance, take this problem with the statement I made about Indians. I saw the statement today in the, from the complaint and now, the statement read that many Indians will vote for whites. And I stand by that.

POM. Everybody we've talked to has said that I think. I mean, what I found interesting was, we spoke to a number of, we spoke to Cas Saloojee, we spoke to many of his colleagues, who said exactly what you said.

AG. [You see now there will be those who, for instance, sooner or later will be...I mean, there is also ??? said that I did not think that the ??? was wise at this time.] I'm not going to be saying that events have not proved that I was wrong. The only difference of opinion is that some people felt very angry about it. But, well, they just stopped at that.

POM. The toleration of difference of opinions is an essential ingredient of a democracy.

AG. Absolutely, exactly so. Exactly so.

POM. What about the PAC? What about their staying outside the entire process?

AG. Well, they've stayed outside the struggle as far as I'm concerned. The only struggle they took part in was at the Sharpeville march, which was a disaster as far as I'm concerned.

POM. So, you don't see them as a serious player?

AG. Have they been? Where have they played? I mean, I'd like to see where they have played.

POM. Well, some people have suggested to us that they could possibly destabilise, derail the process.

AG. Derail the process? Well, what have they actually achieved so that I can say that they have got the ability to derail?

POM. Well, how was it put to us? It's that they may pose more of threat in the future than now. I'll tell you how it has been explained to us and you can inject your comments on a number of things. It was said that there was a whole generation, at least one generation, of youth out there who have no education, who are unemployed, unemployable, who are used to a culture of protest, all they know is how to protest, how to confront, that many of them are having trouble coming to terms with the announcement of the end of the armed struggle. That some consider this almost close co-operation between the government and the ANC is something of a sell-out, that the PAC stands there as a magnet that can attract many of the disaffected young. What would your reaction to that kind of scenario be?

AG. Well, I think it is a very weak magnet.

POM. It's a very weak magnet?

AG. Yes, it's a very weak magnet. What is a fact is that people want peace, people want to live, they want to enjoy the fruits of their labour. Even those young people want shelter, they want food, the best shelter they can have, the best food they can eat, proper education. Now, to them now the only entertainment they are having is doing the terror, things of that kind. But at the same time, you see the attention they pay to shows by Imela(?) and other artists, then you see that they are not just negative, they have an appreciation for the good things of life. So that, you see, all you need now is to give them opportunity to enjoy those things in one way or another.

POM. If tomorrow morning you had a majority government, what difference would it make in the life of the ordinary person who lives in a township or somebody who lives in a squatter camp? Or what difference would it make within four or five years?

AG. Well, what I will say is that the knowledge that there are no barriers, no more external forces keeping dwellings, will result in people using their talents for moving out of the situation they're in.

POM. But do you not think most of those who live in a squatter camp will still live in a squatter camp?

AG. They won't - I mean if they can't get out of it, if we are able to indicate how to get out of the squatter camp and they see examples of people moving out of them, they are going to leave them.

POM. Well, there are these massive backlogs in education, in housing. Where are the resources?

AG. All you got, maybe, is to make the children excited to get to school and know that in school they are actually learning, somebody is actually assisting them.

POM. Do you think that within five years there will be a significant dent made in the backlog of housing and that people in squatter camps will be able to move into more decent housing?

AG. Well, it just depends on the availability of building materials. They should have the opportunity to do this for themselves.

POM. Yes, but to go back to the youth, if in four or five years young people look around and find that the conditions in which they live haven't improved very much, that unemployment is as high as ever?

AG. Now, now, now, well, of course, you see, as far as I'm concerned, if attention was paid to, for instance, building, getting those youth here to be employed in building, those homes will be built in a much shorter time than they are being built at this stage. With the availability of that unemployed labour being put to use the only question is, where are you get the money to still get them food while they are working? But when they are doing things for themselves, I think that it will be possible to get more out of people than you can when they are doing things under pressure from others and benefits which they can't really enjoy.

POM. There's been a lot of talk, too, about the imbalances in the distribution of wealth, the imbalances in the distribution of government services. Do you think that the structure, the types of structure of the economy, will play a big role in the negotiations? Do you think, for example, that what the what the government may want to protect is white economic power? They might be quite prepared to give away political power but what they want to hold onto is the economic power?

AG. Yes, I think that is disaster. I think that would be a disaster.

POM. It sure would, but do you think they will try to do that?

AG. Well, if they are thinking properly they won't think of using that power for selfish ends.

POM. Well, do you think the white government or the government will try to have guarantees, say, relating to free enterprise, that the economic system will be written into the constitution?

AG. I doubt they will succeed in that. One can say that a high level of co-operation between industry and labour is a must for the future.

POM. In the last number of years the trade unions, business and the trade unions, have really been playing very adversarial roles.

AG. Very, very adversarial roles. And if they could regard it as in their interest to do the opposite of that, then there is no stopping South Africa from being the (success) of the continent.

POM. Do you think there will be nationalisation of the railroads, the public utilities?

AG. Post office? Well, as a matter of fact, those are state-owned at present, so that I, and that is something that people have grown to be accustomed to, and I don't see any of it ...

POM. Do you see the government going into any other areas?

AG. Well, what sort of areas would we be thinking of? Would we be thinking of manufacturing?

POM. Say the mines. The mines might be the most obvious ones.

AG. The mines? Well, I don't know that the mines would attract that sort of attention except that perhaps there would be an insistence on representation by the state in the management of these institutions, so that the state is assured that the mines do not adopt anti-national policies and practices.

POM. I want to go back for a minute, what do you see as the major obstacles that Mr. Mandela faces within his own community as he tries to guide this process through to fruition? What are the main stumbling blocks?

AG. Well, I will say that as far as I'm concerned, it's the expectations that have been created in the minds of people in regard to the future. You see, for instance, there is the youth grumble against the statement that the armed conflict is suspended. Now, the expectation that they are going to be consulted at ever twist and turn and the position being this way after the present obstacles have been removed, delivery of the promises does not become possible for various reasons.

POM. And if you look at Mr. de Klerk, what do you see are the main stumbling blocks that he faces within his community as he tries to steer the process forward?

AG. Well, the main stumbling block I see is persuading people to accept a lower role than the role which they have been playing in society. And being prepared to consume less than they have been consuming in the past in regard to the resources of the country.

POM. Interestingly, you didn't mention the violence that is going on as something that could derail the process in the next year or so.

AG. Oh, well, you know, the assumption, of course, is that it is not possible for anything to be achieved in this climate of violence. I mean, it is no good talking about it. With this violence it is just ...

POM. What would you advocate as the steps that should be taken to bring it under control?

AG. As far as I'm concerned, we have to get the responsible people, now, when I say "responsible", I'm not saying the people who are responsible for the violence, I'm saying that you have got to get responsible people to identify the causes, in their perception, and they can then convey their concerns to their followers and in that way be able to get their followers to understand that what is in their interests, that would be in the interests of all. That there should be no violence involved in the process which you have got underway.

POM. This, at some time, would require a meeting between Mr. Mandela - I mean, it seems to me that a prerequisite of any resolution is that they must meet at some point.

AG. At some point.

POM. Do you think Mr. Mandela is sacrificing some of his stature by not doing so? It seems such an obvious thing.

AG. Between you and me, he is. He is.

POM. He's shedding some of that lustre?

AG. Oh, my goodness. But, of course, you see, now, we have got to bear in mind that the man has been in prison. And, well, the people who are advising him are, he is not able to criticise. Firstly, he has no knowledge. That is why they had to have that big conference. And at that conference, for some reason, it was organised in such a way that his idea which would result in Buthelezi and Mandela meeting, is just not on.

POM. When was this conference?

AG. This was, when was it, now? Last weekend.

POM. Last weekend. As you look forward to the next year, what do you see happening? I mean, do you think that we are going to see a broadened negotiation table, or will it be possible to get everybody around a table? Do you see the government agreeing to a Constituent Assembly or drawing the line and saying, no way? What things are out there that you visualise happening?

AG. Well, many things could happen, many different things could happen. My only reason for optimism, such as it is, is that all recognise that it is a choice between peaceful society and no society.

POM. So to that extent, the process is irreversible, do you think?

AG. It is totally irreversible, it is irreversible. For one thing, when you look at the countryside, without the co-operation of the black people who are in that countryside, it is not possible to govern it with your tanks and your armoured vehicles. You govern it during the day, there are knives, it's fine to ambush or to [cause them this] throw Molotov cocktails into them. So, I don't see that an attempt will be made to crush resistance with an iron fist. I don't think the iron fist is going to reign supreme. I don't say that those are irreversible things.

POM. So, are you optimistic about the next year?

AG. Well, I would say I am to the extent that I believe that all human beings have common sense in the end and understand what is their best interest.

POM. Let me ask you a slightly different way. Are you as optimistic now as, let's say, you were on 2nd February?

AG. On 2nd February there was an element of euphoria in the thinking of most people in the country. What the announcement amounted to was something that very few people believed could be announced by the State President. But one can say that as events are unfolding, the reason to be optimistic is even bigger now than it was then.

POM. Finally, the South African Communist Party - what is the distinction between a member of the ANC and a member of the SACP? What is different about them?

AG. Oh, my, you see the African National Congress is a mass organisation that is ...

POM. Is there anything that a member of the SACP believes that a member of the ANC doesn't believe, or the other way around?

AG. No, well, it is difficult for me to say what a member of the SACP believes, but I can say that ...

POM. We've been running into that problem.

AG. I can say that one hears talk of socialism and now not much talk about communism whereas in the Communist Party the phrase "communism" is not being bandied about much. One thing though, you see, that did bring the organisations together was opposition to colour discrimination and, as it is called, apartheid, what has been the focus point. And insofar as communism is atheistic, the African National Congress is not an atheistic organisation.

POM. But do you think, in some way, this close association between the SACP and the ANC hurts the ANC in the black community where there is a very strong religious orientation?

AG. I don't think that many of them, I mean, as far as the mass members of the African National Congress they are not even aware that the SACP is an atheistic organisation. It doesn't enter their minds at all. They are only thinking in terms of it being an organisation which demands rights for all.

POM. Finally, what would be your assessment of Mr. Mandela since his release from prison? Where has he done better than you expected, where has he done not so well? Where has he been strong, where has he been weak?

AG. Well, generally speaking, I will say that he has been very good at enunciating the policies of the African National Congress. I don't think that anybody could have dealt with the questions that have been asked better than he has. And he has helped many people to really grasp what the African Nationalist Congress stands for. He's been very strong. And then, of course, I don't know to what extent I would say that the problem of Natal's violence has challenged his ability to solve problems at this time. I mean, I can't say he has got to the end yet because I think that his role is not so much Buthelezi but that he may find himself isolated from the organisation leaders if he does what he seriously must do. I'm very worried.

POM. At this time next year, where will we be?

AG. This time next year? Well, I can make a guess that, well, assuming that we are still alive, that we will be really seeing the end of apartheid as we have known it.