This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

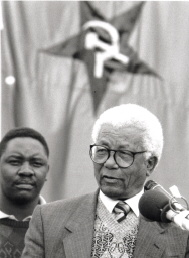

03 Oct 1996: Sisulu, Walter

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Once again, Mr Sisulu, thank you for the opportunity for talking with you. I think this is the sixth or seventh year now that we have our little conversation. What I would like to talk about today is, and it came to me from reading President Mandela's autobiography, he talked about when you had been moved to Pollsmoor Prison, you, he, Kathy and Raymond Mhlaba, and he said then he had to go into hospital for an operation and that during that period Mr Kobie Coetsee came just to see him, but he had a paragraph in his autobiography that struck me. And then when he got back he was put in isolation on his own and he said in his autobiography that in a way he didn't mind this because he had made a decision that he would establish contact with the government and he thought that being alone made it easier for him to do because he knew that if he was upstairs with you and Kathy and the others that you would probably oppose the decision but since he was on his own he could initiate contact. Would you have opposed contact with the government at that time?

WS. No, I think his difficulty would have been on the other side. When he was with us he was bound to be discussing matters with us. They would not have liked that. They in fact did not like that, that he should make contact with us. They deliberately isolated him because they also wanted to have a discussion with him so if he remained with us it's not so much the opposition but as far as the opposition is concerned I think all others agreed with him unanimously, no problem. I was the only one who made reservation to say that it would have been preferable if we had pushed them so that they take initiative and I think we should not be in a hurry. Not that I was opposed to it in principle, I knew it was the correct way, but timing was very important from our point of view, and even the external mission. For this reason I thought we must be steady and all others had agreed, no problem.

POM. When you said that you should have pushed them a little bit more, what do you mean by that?

WS. Pressure of forces at our disposal, international forces, the MK forces, the mass movement in the country had reached a very high pitch and I was saying let's watch this situation a bit and let them think about it and let them take initiative, we might have difficulties with them. That's what happened. I don't think even in my case it meant opposing.

POM. It was tactical.

WS. Tactical approach.

POM. Now when the government did respond to Mr Mandela's request for a meeting were you and the others sceptical of what the National Party really had in mind or did you believe that they truly wanted to find a way or were beginning to try to find a way out of the corner into which they had painted themselves so successfully?

WS. We had made a practice in jail even before Rivonia, in previous times, the first thing when you meet the authority is to educate them about the policies of the movement. We have never stopped that so that when we got to Robben Island this was the approach whenever there was an opportunity of the government officials coming to see the leadership. The first thing is to outline the policy, indicate that this is the line so that the question we knew that the pressures were going to play an important part. We must give them a way for giving in to negotiating. We had thought that we had powerful forces at work that they can't completely ignore us. They must move one way or the other. That's how we looked at it.

POM. But you didn't want to, am I reading you correctly? You didn't want to put them in a situation where they would appear to lose a lot of face?

WS. Yes and no. Right from the beginning even when we established uMkhonto we indicated that an approach, an exchange of views, discussion of the situation is the best thing for all to understand, that the period of conflict, armed conflict, may have created, it may create difficulties. We hoped that they will realise that the answer is to discuss issues.

POM. You talked about government officials coming to Robben Island to visit the leadership. Did they do that frequently?

WS. Yes they did. The Minister of Justice now and again, he was in charge of prisons, came, if not him his deputy or some other officer. Not only were we doing that with regard to the government officials, our visitors had to be educated as to what our strategy is.

POM. So in a sense dialogue between the ANC and the government really goes back to Robben Island not to just 1985?

WS. Yes it goes back to Robben Island, yes. When for instance the Eminent Persons Group came with their own proposal we were already discussing the situation and Mr Mandela had a chance now there because he was alone whereas the jail authorities would have been reluctant to allow them to have discussion with Mr Mandela. That was also a factor, when they came in we exchanged views, they in particular exchanged views with Mr Mandela. We were not allowed and I think by that time he was already isolated.

POM. Now when the government officials came to Robben Island what kind of things would they discuss with you?

WS. Well the treatment. We would naturally tackle the current situation, the issues that are affecting us in jail. But in doing so we would also discuss the general political situation in the country, giving a chance to giving our policies, to say the answer is one. It gave us the chance always to refer to that. Now although we were no longer together with Mr Mandela he more or less knew our views and at least I knew his thinking, his way of handling the situation.

POM. Now would they listen to you, respond in any way, engage in any kind of dialogue?

WS. They listened to Mr Mandela because we adopted a policy whereby we appointed Mr Mandela as leader in jail. They discussed with him because it was much easier. He in turn would consult with us on issues and generally they had respect for him and discussed in a reasonable, shall I say responsible, way. That's what would happen and all this led to shifting the goals.

POM. Shifting the goal posts.

POM. Now when he met with State President PW Botha did he discuss that meeting with the leadership afterwards?

WS. I am no longer sure whether it was - I think it was at the time when he was isolated.

POM. That's right, it would be 1989.

WS. Yes. He would not have discussed it before. He would have merely reported after.

POM. What was his report on? How did he find Mr Botha? What was his impression of him? Did he think that this was a man he could deal with?

WS. No I don't think he did, I don't think he thought that this is the best man, but he thought he was powerful enough and he is the man to convince, it's a man to put your case to although he knew that he was one of the most reactionary Afrikaner Nationalists but I think he thought it wise to have a discussion with him, seriously.

POM. All these allegations that have arisen by Colonel de Kock, I'm just talking about him specifically at the moment, whether it's the targeting of individuals within the country or the assassination of foreign Prime Ministers or the naming of Generals as being involved and in some cases even PW Botha himself and presumably there are yet other people who will be named in one way or another. Does any of this surprise you?

WS. I don't think exactly it did. They were doing things already which indicated to what extent they would go. The attack on Maputo of our people there and I think there were a large number, no less than fifty. A similar attack was made in Lesotho and apart from various issues, various occurrences in the country itself when the three disappeared in Port Elizabeth, we had no doubt they were murdered, cold-blooded. And when it happened also with the Craddock group we knew that they are killed, there can be no doubt about it, so that we had an idea of what was going on. They were in a desperate position and they could do anything. So to that extent it was not surprising to us.

POM. Do you think that the Cabinet, the National Party Cabinet, approved of these actions or do you think they deliberately kept themselves in the dark?

WS. I think the Cabinet discussed the security. They would put the issue of security and that type of principle they would discuss it and approve the strategy, perhaps not the details. When they started talking about onslaught these were the ideas that they could be ruthless because the situation they interpreted to be desperate and therefore they were desperate themselves.

POM. So when you find various ministers making statements, and so far every minister has said, "I never knew this was going on, I never knew that was going on. This comes as an utter shock to me." Do you find these statements believable or do you find that they are just simply denying what in their hearts they knew?

WS. They are simply denying because they had the security machinery, I can't remember what they called it.

POM. The National Security Management Council.

WS. They therefore discussed the situation, they would discuss it in detail. By and large the leading ministers would know what is happening. It may be that some of them may not have known. I don't think it's an issue they would discuss in a full Cabinet and I think that's why they had a Security Council and with some leading people to discuss details of what their strategy is going to be or will be.

POM. Do you think that they will come forward before the Truth & Reconciliation Commission or that they will try to sit it out and just take their chances on not being prosecuted, or that there's neither sufficient time or resources or even a will on the part of the state to push the thing further?

WS. You want to know what I think are likely to be the results?

POM. Yes.

WS. Well I think they are in a difficult position. They have been exposed. They know these things, they know how dangerous they are. They know the brutality that has taken place. I think they are now exposed to an extent that they must come forward. That's what I think. I don't see how they are going to evade coming forward and discussing the issue. I can't see how. They would like to minimise the brutality that is exposed. They would want to excuse themselves, those who have been in the forefront. Now you take the Generals both in the army as well as in the police force, they would like to explain their position because now they also are shocked with the situation even though they were part of it, but I think they are shocked with the situation. They just didn't realise how far it had gone.

POM. So they had given an overall instruction but never bothered to find out exactly what was going on?

WS. The consequences, yes.

POM. But that's not an excuse. They are still accountable for the actions of their subordinates. That's the way command structures work.

WS. Yes, yes. That is why they must explain themselves, push the blame as far as possible, perhaps even to the lesser officers so that they deny that they on the top were in the know of what was happening. And that is why I think they are compelled with this situation to come forward so that they put a case. They now know the public is alarmed and shocked. They are shocked themselves.

POM. So this whole process is good for the country? It's good that the truth gets out?

WS. It's good for the country and it's good generally to come out with this situation. In the end, in the final end it's good even for them. Well you get people saying that, well, the whites were liberated themselves by this struggle. It liberates their minds when they discuss it because they must fit into the society. How does the society look at them in this situation unless they explain? Explain perhaps merely to minimise the brutality that has emerged.

POM. Now you know I'm not publishing anything until the year 2000, my book won't be finished, I'm covering from 1989 through 1999 so I haven't published anything that I've collected over the last few years, what people say is all in confidence. I would just like to hear your comments on, if you will, on the Bantu Holomisa affair. Do you think the whole thing could have been better handled in the end?

WS. Yes I think so, I think it could have been better handled. I blame him, I think he took things for granted. I think it was largely lack of understanding of the movement. But on the other hand I think the leadership was too much in a hurry, it was too hasty not allowing the situation to be handled in a more reasonable way. There certainly was anger. Now you can't be guided by anger when you deal with a situation of this nature. You have got to depend on the nearly scientific analysis of the situation but if you handle it with anger you must necessarily go wrong and there was that element in Holomisa. It was not necessary to give an impression, I know it was not the intention, that you are siding more with Sigcau who was guilty, but guilty at another stage. This chap Holomisa handled that situation badly but we also handled it badly.

POM. I've known him since 1989, that was the first time I met him when he still was head of the government in Transkei and he always talked about the ANC and how he was trying to operate on behalf of the ANC.

WS. I think he did have that in mind. That's why I say that there was a complete lack of understanding of the movement and then an over-exaggerated picture of himself and that is why he went wrong. I have no doubt he has the highest respect for Mr Mandela in particular and even from a traditional tribal position he has the highest respect for Mr Mandela. And to reach a position which is in conflict shows that he overestimated his position. I like him and he has done quite a great deal of service when we went to Transkei on issues, so I had some soft spot for him, but I know that once he handled the situation that way there was no way he would face the wrath of the executive. I don't agree with everything they have said. I think they should have been a bit soft, but I know that the movement is angry. That is the situation. They themselves are responding to the anger. People love the organisation and when you speak defiant of its authority then you are in trouble.

POM. I thought he might in the end have gotten a severe reprimand or even a suspension but that the ultimate wouldn't have been taken.

WS. Yes, even there he did not allow them to exercise that because he went there despising the people who were on the committee. Now that's also lack of understanding and he made it impossible for them to take a softer line and I don't think that they themselves were really thinking along those lines, but because he was provocative he was making silly statements and making statements which amounted to defiance so he was now creating that situation. Nonetheless I think that a softer line would have been better and not only for him, also for him to have a way of retreat, he should have handled the situation differently. Starting point, too much in a hurry and as if it was an emergency. It was not.

POM. One thought that passed through my mind is that he always saw himself as a General and that he had been 'the head of a government' and used to doing things his own way, acting on his own.

WS. He had had great authority which made him feel that he can handle the situation such as faced him.

POM. When you look back on all the time that you spent in prison, 27 years, this is a funny question, but what were your fondest memories of all that period and what are your worst memories? Or do you have any kind of fond memories?

WS. Well yes. In the first place it had an effect of putting us together, of getting even us as members of the organisation to be closer together, to understand each other better. Then also from a unity point of view of the movement as a whole mixing with the PAC, with AZAPO, with the Unity Movement was not to the advantage of the authority, it was to our advantage although it was intended to punish us but it really was in our favour and I am fond of that period, the unity that we forged as being together.

POM. When you say it was in your favour to be with the PAC and AZAPO and the Unity Movement, could you talk a little about what you mean by that?

WS. Let me just give an example of a young man like Neville Alexander, high intellectual, born and brought up in the Unity Movement and the Unity Movement has specialised in theories, starting politics from a theoretical point of view and despising our methods and therefore despising the leadership of the ANC. Neville Alexander came to Robben island serving ten years. He was influenced by this trend but as a result of discussions, living together with us he had high respect for the individuals he has met, the leadership in particular, and therefore realised that there were false impressions which were created by their leadership to them, the younger people. I was in a fortunate position of being respected by people like Neville Alexander. I worked with him on a number of things, general problems of the community, and in that way we were able to influence each other and understand each other and I think those are moments of which I can say I am fond of those moments. I recall them.

POM. And the worst moments?

WS. The brutality which was not so much exercised on some of us but to the leadership, the manner in which they were treated. Take for instance on 28th or 29th May 1976, suddenly it was the practice of jail authorities suddenly to come up, search you, but this day they came as a big crowd and had planned their invasion. Then they assaulted some of the people. It was a bloody affair. Now that moment always sticks up. Those are worst moments. I myself on that day when they came to my cell and demanded hands up, get against the wall, I was a bit unwell and I was deciding in my mind whether to fight in whatever short manner but do something. I thought well I am not likely to escape, even if they don't kill me by hands they are going to keep me the whole night and develop through pneumonia and so on, might it not be better that I fight back. Those were the thoughts which came to me. And I should imagine that those were some of the thoughts that affected some other people. For instance those who also fought back and I think they were thinking of issues like this. Should we consider surrendering or should we fight back? There was a fight within various cells on that day. I was giving my example, that is I thought of that but I decided otherwise. I said, no perhaps not.

POM. It was better to wait and fight another day.

WS. Yes.

POM. Do you always bring that kind of thinking to the way you analyse things? You've a very, and maybe it's because you spent so much time not just in prison but trying to achieve what you have achieved, but you always seem to take the longer view not the immediate view?

WS. Yes certainly I do. I have learned to be very cautious even if I were to use militant methods but it takes time to think over the issues, analyse them before you act. When Sophiatown, this is now before Rivonia, when Sophiatown was moved we unfortunately used a slogan "Over my dead body". We said so to the mass meetings. That created an impression in the minds of the people that you mean you're going to fight it out, physically. There was no other meaning in the minds of the people. As a result on the day when I think about 1500 army and police surrounded Sophiatown the question was that night, what should happen? There were others who said let's fight it out, let's fight it out, we have committed ourselves by this slogan. Now I took the view there that that will be suicide. Rather let's find something else in order to avoid that. I know and it happened, it gave a very bad impression to the youth. It was a shameful retreat to them and yet I think it saved life, it saved our situation. I'm giving an example of some of the ways I look at things.

POM. So the saving of life is?

WS. It's not only saving life, saving the very movement, that if you did anything that is along those lines, plunge the country, then the movement will be damaged.

POM. Will it be because so many of the leadership might have been killed?

WS. Killing would include the masses of the people, it will include a number of leaders and it would merely be a false militancy that goes in fact against your very objectives.

POM. Because it was a situation where you couldn't win anyway?

WS. A situation where you cannot win and therefore the result will be the loss of the faith in the movement and loss of your best men for nothing.

POM. When you came out of jail before Mr Mandela you had meetings with government officials, looking back just on that period which ones impressed you and which ones left you wondering whether they were really serious about changing the whole order of things?

WS. You are now referring to?

POM. I am referring to when you were released in 1989.

WS. We did have discussions with the government leaders at that stage. We did tackle issues, we would meet the Minister of Justice, meet the Minister of Police but the issue was not so much the general political picture, you were concerned with issues that affected the country at the time. So there was no real general discussion with the government at that stage. The first discussion was when we met the government at the beginning of negotiations. That's the time when one looked at the situation very seriously.

POM. When you look at those first meetings, when you looked at the government side, who impressed you as being really genuine about the want to bring about some kind of inclusive political settlement and who did you think had deep reservations and were very reluctant, so to speak, to take part in the process?

WS. I was impressed at the first meeting and I thought the leadership of the Nationalist Party was quite genuine. I liked the statements which were made both by Mr Mandela as our leader and De Klerk and when they said that it's not a question of who wins, it's a question of (I'm not using their words), the question is the people must win, that's what it means. There is no question of who has won. In other words there must be no question of putting blame on others. The effort must be let the people win, the negotiations therefore must go accordingly. What I am trying to say is that the first meeting happened to be the only meeting I attended on the negotiations, it impressed me a great deal and I thought both sides had something tangible. Later on I was no longer sharing that view. I thought that the Nationalist Party has reservations. They have accepted the question of a negotiated settlement but on their own terms. They still hope to win the power and the only reason why they were doing so is because they thought they can change the situation. I thought that was the real fundamental policy on which they were basing themselves.

POM. When you say they wanted to change the situation?

WS. You see you will realise that there was a question of developing of some methods which were called the third force. The third force was intended to weaken and undermine completely the strength and the power of the ANC. In other words they would talk but the movement must be weakened so that they still find a way of strategically coming up and giving a lead. The leadership should be - I don't know if you understand?

POM. I do, I get you.

WS. I say at the first meeting there was not this in my assessment. There was good intention on both sides but I soon discovered that, no, they are regretting the issue, they don't want to abandon power, they want a way out and they thought this third force was the way out.

POM. Now are you convinced in your own mind that De Klerk knew and approved of the activities of the third force or were these other elements within the security forces and hard-liners in the party operating independently where he didn't really have the control he thought he had?

WS. No I think that generally it was the policy of the Nationalist Party which he approved. The individual acts may not necessarily have been approved by him but the general line, that of speaking double tongue, wanting to negotiate and at the same time undermine the movement, that is the strategy of the government. In that you have the elements therefore of using the third force. The details of the third force may be individual strategists.

POM. Was this the reason for the almost complete collapse in the relationship between President Mandela and De Klerk? It began on such a high note of him describing him as a man of integrity and then it slowly began to drop and then it degenerated into hostility and bitterness on both sides.

WS. When Nelson described De Klerk the way he did he was genuine himself, he meant it, but when he discovered that De Klerk was not genuine there was something behind it. I think it is that situation which made him think along those lines and there have been bitter exchanges between him and De Klerk. I am describing the same thoughts that Mr Mandela saw when he changed his mind about De Klerk. So we were one in analysing the situation and perhaps it's a question of degree. When Mr Mandela loses confidence he goes to extremes. I don't. So there are those differences and I think that up to now that feeling is still there and I give a bit of credit at the same time while condemning. I think that De Klerk has played a part. It was boldness that made him take the line he did and within the Nationalist Party there was this competition between him and PW Botha and I think he took a bold line but it was within this strategy.

POM. What do you think moved him from being so bold initially to being so cautious and almost counter-revolutionary in the end?

WS. Well you must know that he was faced with a very serious situation leading the Nationalist Party which has for years been hostile to the black man. The very thought of talks was a serious affair, not an easy matter. On the other hand I think the intellectuals of the NP were beginning to see you can't oppress people indefinitely. Some way must be found but the consequences they never had perhaps gone into deeply. I don't think that they really meant surrendering power, therefore the general line would be we still must maintain some power.

POM. I think from his point of view he feels that the ANC and maybe Mr Mandela in particular have never given him sufficient credit for the constraints he was operating under, that he all the time had to bring his party with him and in a way that he was negotiating himself out of power which very few people in the world have successfully done and survived politically, that he wasn't given enough appreciation of all the difficulties that he faced and that he wasn't as free an agent as perhaps the ANC thought he was.

WS. There is that, we can't ignore that human feeling. The gravity of the situation must tell us that they also had been faced with a very difficult situation, a very difficult situation. But he did not analyse the statement made by Mandela to say this is a man of integrity. He missed that point, he did not examine it carefully because he would have been careful in his manoeuvring, I think he exposed himself that he was not the type of man that Mandela was describing. He created that situation but we too had known and perhaps did not consider the problems that a man like him faced. So there is that, but by and large it did him greater damage to be party to a strategy that was soon to be exposed. I am saying therefore that even De Klerk knew about the strategy of giving certain aspects that maintain power work in such a way that he will never lose power altogether. That is the strategy of the NP.

POM. Do you think people like Roelf Meyer come from a different generation and tradition or that there are still elements of the old NP embedded in their thinking, that this talk of being the majority party in 2004, which to most people is fantasy ...?

WS. I must say that I think there is a conviction in a man like Roelf Meyer. I think Roelf Meyer has realised that this situation can't be changed in any other way. These people have come into power and sooner or later I think he will find a place in the movement. He is thinking of his prestige within the white community, particularly the NP, and being highly respected. I think he does not completely approve of the NP's strategy. I think, I may be wrong, but I think as an individual he has come to a different conclusion. I think he realises this man, this situation has come to the point in which it is, therefore once you come to that conclusion you say, how best can we handle it? Not, how best can we destroy it.

POM. So you have hope for the likes of Roelf Meyer. You think they represent a newer, more open generation of Afrikaners who want to see the country prosper and grow?

WS. That's my view. A man like Roelf Meyer and Leon Wessels, these are the men I think have got a different approach on the situation.

POM. This is my last question, do you think there's a battle on in the NP for the direction in which it's going between the likes of a Hernus Kriel and the likes of a Roelf Meyer?

WS. Yes I think there is. I think there is. There was once a statement, I don't know who issued it, on what conditions it was, it mentioned that they think that Roelf Meyer will soon be in the ANC. But I think he has got good qualities of leadership that he doesn't want to blunder, that he has been able to create confidence that he is still with them. He doesn't want to quarrel with the NP, he does want to find a way where his people can fit in. I think that's how he looks at it.

POM. OK I will leave it there for this time. Thank you once again. It's always such a pleasure to talk to you. I really enjoy it.