This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

Overview of 1994

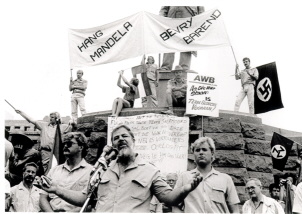

In the opening months the final acts of brinkmanship were played out. Some, like the Ciskei's Oupa Gqozo, simply folded their cards & joined the TEC, a step that was contrary to the position adopted by the Freedom Alliance. Among right wing Afrikaners there was growing anxiety & anger as elections grew closer & their leaders fumbled for a way to extract concessions from the ANC & NP on the question of Afrikaner self determination. The AWB offered nothing more than a blustery promise to fight & the powerful oratory of Terreblanche. Both the government & the ANC, however, discounted the AWB as a real threat, a tiresome irritant capable of causing disruption but not a real threat to stability after the elections.

Constand Viljoen was another matter. The retired general commanded enormous respect in the SADF and among former members & in the countrywide network of commandos. His threat that he could mobilize a force of up to 30,000 to fight for the cause of Afrikaner self- determination had to be taken seriously. The ANC did not for a moment underestimate the turmoil & chaos that would erupt throughout the country if Viljoen was able to make good on his threat. The question was: how much of his threat was bravado & in the event that his threat was real would the SADF defend the "new " South Africa against an insurrection led by a soldier revered both by the rank & file & the officer corps?

When the deadline of 10 February for the registration of parties for the elections passed &, Inkatha, the CP, the Afrikaner Volksfront, and the government of Bophuthatswana had failed to register the deadline was extended. Buthelezi further raised the ante when he told his supporters to form self defence units to defend themselves & resist the rule of the ANC & "their communist surrogates." "We must defend our communities with all our might," he warned. "We must defend & fight back." Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini told President de Klerk that he was prepared to set up a Zulu Kingdom. In a memorandum he presented to De Klerk, the King rejected South Africa's interim constitution. Undeterred by the political commotion the IEC hired 10,300 election monitors.

In an effort to somehow bring Inkatha & the Freedom Alliance into the fold the ANC & NP offered concessions: a constitutional principle on self determination, mechanisms to consider the feasibility of a volkststat, two ballot papers (national & provincial), a provision enabling provinces to draft their own constitution & raise taxes, a principle ensuring that the final constitution did not substantially diminish provincial powers, & the granting authority to provinces to rename their provinces, with Natal renamed KwaZulu/ Natal. The IFP did not bite.

Concerns mounted. The international community urged Buthelezi to join the process. The ANC & the NP grew more anxious. Further concessions were made: powers were granted to provinces in all areas of their competency that would prevail over national powers, the power of national government to override provincial governments was severely limited & the date deadline for registration of parties for elections was pushed back from 4 to 9 March.

On 1 March Mandela went to Durban to meet with Buthelezi. The ANC agreed to submit differences between Inkatha & itself to international mediation, provided Inkatha provisionally registered the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) for the elections. Mediators were agreed former British Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington, former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger , the chairperson of the Venice Commission on federalism, Professor Antonio La Pergola, Goldstone commission assessor, Judge Prafullanchandra Bhagwati of India, Professor Washington Okumu, a Kenyan, & constitutional experts from Germany & Canada, & a Black American judge.

Before their arrival, however, events in Bophuthatswana brought an end to the threat of white ring wing resistance. Unrest there, stoked by the ANC, against Mangope erupted in early March. Public servants, including the police, believed that Mangope's vacillation on whether to take part in the elections jeopardized their pensions. They demanded payment since Bophuthatswana would cease to exist as a sovereign entity after the elections.

Mangope called on General Viljoen, his ally in the Freedom Alliance, for support. But Mangope did not want the AWB, although also a member of the Freedom Alliance, involved since he regarded the AWB as ultra racists.

He was concerned that its presence in Bophuthatswana would only provoke his own army to mutiny. Viljoen agreed to help, also on the condition that the AWB, which he despised as an undisciplined group of blustery buffoons playing at being soldiers, was benched. Terreblanche, however, ignored Viljoen's plea to stay out of the way & on 11 March bakkies full of AWB 'soldiers,' swilling brandy & shooting guns into the air made their way into Mmabatho, Bophuthatswana capital.

A picture captured on video & played & replayed on SABC TV & on television around the world, caused white South Africa to catch its breath, pause, and draw back from the abyss. Three AWB men, one dead & two wounded, propped up against the side of their bakkies, are watched over by Black men with guns. Almost lackadaisically, one of the Black men points his weapon at the two & as they plea for their lives, he shot them dead, one shot each. Whites, who were inclined to fight for the Afrikaner state they insisted as being their right, saw a glimpse of what the future could look like & thought twice about where their rebellion could lead.

Viljoen was already in Mmabatho. He had sent in 1500 men ahead of him, bearing only sidearms & had another 2500 in reserve. They were to reconnoitre at the airport & be provided with arms by the Bophuthatswana military loyal to Mangope. With the AWB's arrival Viljoen left, immediately formed a party the Freedom Front-- & announced that it would participate in elections.

Buthelezi was still on the sidelines. On 28th March 1994 exactly one month before elections -- - thousands of Inkatha members armed with traditional weapons marched through Johannesburg to rally in the centre of the city. A breakaway group marched on Shell House, the ANC HQ. Whatever the circumstances, snipers in Shell House opened fire & in the carnage 53 Inkatha supporters were killed. The ANC insisted that the Inkatha tried to storm Shell House.

No evidence emerged to support that claim. Mandela refused to allow police to search Shell House.

In April the TEC declared a state of emergency in Natal and sent in the army as a result of the upsurge in political violence. Political campaigning there was risk fraught. 'No go' areas abounded on both sides of the political divide.

The mediators arrived in SA on 10 April but Buthelezi refused to meet with them when the ANC would not agree to a reconsideration of the dates for the elections included in the frame of reference for discussion. Without a frame of reference the mediators left almost before they had unpacked their bags, except for -- Okumu.

On 15 April, 10 days before the elections, he persuaded Buthelezi to participate. The circumstances in which this "miraculous" turnaround happened are too detailed to recount here -- almost farfetched to go into here. Stickers were used to append the picture of Buthelezi, the logo of the IFP on millions of election ballots.

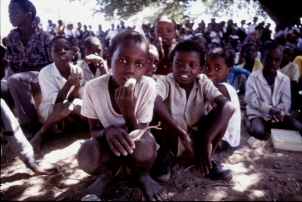

On 27/28 April an overwhelming number of South Africans went to the polls. There were extraordinary scenes of Africans, old huddled men & women, women with all their children in tow, men standing proudly, all decked put in their Sunday best waiting for 3 to 4 hours in long lines outside polling stations before entering, having their ID checked, their thumb stamped with dye & the ballot handed to them. They marked it & deposited it into the container. They had voted. Slews of international observers declared that the elections were free, fair & peaceful. There were some delays & glitches during the counting, but they were only of passing account. On the evening of 2 May de Klerk graciously conceded.

When the full count was in the National Party had won 20.6% of the vote, the ANC 62.6%, the IFP 10.5% the Freedom Front 2.2%, the Democratic Party 1.7%, the PAC 1.2% and the African Christian Democratic Party o.5%. Thus, the "miracle": the ANC did not receive two thirds of the vote, which would have enabled it to write a final constitution to its own liking, albeit it would have to incorporate the 36 constitutional principles agreed during negotiations. The IFP won a majority, albeit a slim one in KZN and the in the Western Cape, a coalition of the NP & the DP ensured that it would not fall under the rule of the ANC. In all results that gave something to everyone & no winners take all.

On 10 May, Nelson Mandela was sworn in as South Africa's first democratically elected President, Thabo Mbeki as first Deputy President & FW de Klerk as second Deputy President.

In Mandela's first Cabinet the government of National Unity (GNU) consisted of eighteen ministers from the ANC, six from the NP & three from the IFP. Mandela had inherited a country of over 40 million people. About 6 million, almost all Africans, were unemployed, poverty was rife and about 10 million had no running water no electricity.

The Freedom Front, which had won nine seats, exercised its right in terms of the constitution to elect a 20-member Volkstaat Council. Its aim was to enable proponents of a volkstaat to pursue the establishment of such a volkstaat constitutionally. In June the National Assembly met in its capacity as the Constitutional Assembly with Cyril Ramaphosa as its Chairperson & Leon Wessels as deputy Chair. The work of drawing up the final Constitution began.

In August Buthelezi raised the issue of international mediation in terms of the agreement signed by himself, de Klerk & Mandela on 19 April to clarify outstanding constitutional safeguards for the Zulu kingdom. The agreement, which resulted in the IFP entering the election just seven days before voting began, committed the government to mediation immediately after the election. Buthelezi said that his correspondence on the matter had, however, gone unanswered. Mandela's office said no correspondence had been received.

In November Ramaphosa announced that the CA had taken legal opinion on the matter and was advised that it was not legally bound by the agreement concluded between the ANC, the IFP and the NP. Buthelezi reacted with defiance, warning that the GNU would not last 'for even 12 months' if the ANC reneged on its promise of international mediation. The Zulus wanted their monarchy entrenched in the transitional constitution.

At the close of year, Mandela offered an olive branch. He told the KwaZulu/Natal regional congress of the ANC that the ANC would not breach its agreement with the IFP on international mediation. He said that the ANC would arrange a meeting with Chief Buthelezi to discuss the mediation.