This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

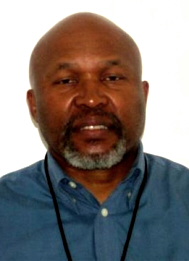

26 Aug 1992: Morobe, Murphy

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Maybe, Murphy, you could start with describing your job at CODESA, what you thought of the organisation and management structure, what it's strengths were as a negotiating forum and what you saw as its weaknesses as a negotiating forum.

MM. My job basically was to be the overall co-ordinator of the entire administration process that the process required. Now considering that you had different parties with different interests and different information in the way of what they would like to be the case, even as far as administration is concerned it was quite a difficult thing in the beginning to get to a point where I was eventually appointed to head the entire administration. The job entailed basically putting in place an effective and efficient infrastructure that would service the entire negotiating process at the level of CODESA, which wasn't an easy task given the fact that one had to make sure that whatever you did you at least did not actually run foul of some of the members of the process itself in terms of their specific interests. So one had to take a fairly balanced approach to handling administration and not become biased towards one side above the other and that was a big challenge that one had to face, especially for me who with a known background of being in the UDF, in the ANC as well. But I think that at the end of the day we had the Management Committee voting for me to take the task, I think largely because of my own experience. I think perhaps one could say I am one of those who had a work experience which was much more public than many well exposed people, so people were able to relate with me and my ability to do the task at the level at which they required it be done. And also I think the fact that at the time when I was called upon at CODESA, I was also involved in the private sector at PG Glass and I think my credentials were more acceptable to most of the parties.

POM. How would you have regarded CODESA 2? I heard two different views that you can expect, these two different views of many things, as a forum that would produce a progress report that would move on from there to another point or as a forum that would produce final reports which would be implemented and acted on?

MM. Well as I say I think the different actors saw CODESA differently and I think in my capacity as a CODESA administrator I only experienced the process mainly at that level where it reflected both different sentiments as to how this whole CODESA 2 worked.

POM. Did you see it reflected in, did this perception exist, say, on the ANC side and on the government side from the beginning of CODESA 2 or did it emerge after the deadlock?

MM. No, no, I think it's still there. I think one of the main causes of those different perceptions I think stems from the two main parties own positions vis-à-vis the whole question of transformation for SA and that the ANC's perception of the government has been that the government actually sought to have CODESA become more like a talk shop, something that will extend government's stay in power. Whereas the ANC, the ANC had to address a constituency which was more interested in knowing exactly when are we going to be free in this country, so they had no luxury of actually extending the negotiations endlessly. So that is from whence these two perceptions actually derived and I think that the ANC was more interested in seeing CODESA 2 basically coming up with more definitive decisions and agreements on some of the issues. So as the government has been putting the view across that really now we may actually have got CODESA 3, we may even have CODESA 4, etc., which the other parties didn't agree with.

POM. I have a quote here from a professor at, I think, Stellenbosch, Philip Nel. After CODESA deadlocked he wrote in an article, he said, "CODESA ignores the fact that the ANC is a mass political movement and not a traditional political party. The ANC's legitimacy has rested on its ability to project itself as the representative of people's power. Because of this the ANC is exposed to a myriad of grassroots influences which the leadership can ignore only at its peril. Ideologically and emotionally the ANC can't be drawn into an elitist arrangement even if material improvements of daily living standards of supporters were to follow soon thereafter." He goes on to say, "The followers of the ANC made it clear that the grassroots would not tolerate an elite pact. Mass action was decided on to address the fears of its followers that the leadership was no longer interested in people power. This implies that a future negotiating forum has to accommodate the people's character of the ANC." Would you agree with that assessment?

MM. It's fairly accurate I would say. I think it almost tallies with my own feelings of the process. I think when one saw it even half way through, or through CODESA 1, there were already beginning to be very strong feelings expressed about the way in which CODESA was coming across as being more secretive than it actually was, than the process warranted, and that precisely because the ANC had come from that tradition and character where people have come around to actually demand to become part and parcel of any process that affects their lives, that the ANC and its alliance partners could not ignore that kind of sentiment.

POM. Did you have a case where the negotiators more or less lost touch with the grassroots, became, as he describes it, an elite bargaining with the elite of the government, trying to reach an agreement between them which they then would announce to the masses?

MM. No not really. I know for a fact that there are a number of people who had actually been on the road, in fact the crop of people who consist of, who make up the ANC's negotiation team. Since CODESA had begun almost every weekend they have been on the road because they had actually trusted the actual essence of what the professor is talking about, the need to keep people fully informed at all times. Now even that picked up momentum to such a point where they were beginning to be feeling that now all these problems that people do have - I think it's going to come around with more education as the process unfolds, people will get to know more about how these processes actually took place. It is precisely those meetings where, I mean take, for example, right now Cyril Ramaphosa has been having meetings with Roelf Meyer. Whilst in themselves they are not the actual negotiations it can be argued that, some people could argue that look you have taken a decision that we will not meet the government until certain conditions have been met and why are you meeting with Meyer? But I think an understanding of the process of negotiation when one understands it properly we accept in fact the need for those kinds of contacts to happen because what they will be doing will be actually just to pave the way and make sure that the atmosphere is such that it does not degenerate to an extent where it may be totally impossible for the process to be taken further as and when the government decides to respond to these fourteen demands of the ANC.

. Now the point I'm trying to make here is that you've got different levels at which contacts, consultations and negotiations take place and those levels often, the need to make contact, the contact itself is often confused for the actual negotiation and this is a delicate part which I think the ANC also can't ignore. It will have to consistently keep people informed as to what are its intentions because if that doesn't happen you will not be able to blame people when they make their own conclusions because there is no facility that affords them the privilege of actually understanding what the intricacies of that process actually are.

POM. A generalised feeling we get from talking to people is that had the government accepted the ANC's offer of the 70% veto threshold in the constitution, 75% on the bill of rights, with the various deadlock procedures built in, had the government accepted that there might have been a lot of trouble having it accepted at the grassroots or even at the middle level of the leadership of the ANC itself. Do you think that is an accurate reflection of sentiment both within the organisation and on the ground?

MM. Well sure, yes, I think there was that sentiment and I think that the leadership or the negotiators were going to have to find a way of actually explaining basically what the actual import of their agreement on that basis was on which they had then agreed in terms of these percentages to the people and let people understand. The bottom line for people is to know that when those guys come back from having agreed to 70%, 75%, whatever the percentage is, all what they need to know is whether they have not been sold out. So it was going to be a case of how Cyril Ramaphosa and Mohammed Valli Moosa are able to tell people that, look, they have agreed on these percentages and it's going to mean a materially different SA for us in this respect. So people would then have to say whether they accept that or not.

POM. What's your own feeling? Would they have accepted it?

MM. Well they could have but it's not easy to tell now that things have taken the course that they have taken. But I think the higher percentages would have been very difficult considering that in fact we move from a premise that when one talks of democracy there are established precedents world-wide, accepted precedents all over the world in how you reach majority decision making positions within any institution and I think that the feeling here was that we have been put in a situation where we would not be able to implement any significant policies or programmes that we may want to in terms of the way in which the government and its allies were pushing the percentage positions. So in the end I think it was going to be a case of whether having agreed, are you going to be able to change SA for the better or not with this position? Even if, assuming that, for example, they had accepted those positions and within six months or one year or two years the ANC gets itself caught in a parliamentary situation where consistently they are not able to break that barrier, that those percentages have played themselves in, it's not difficult to foresee what the likely consequences on the ground of that can be because it can result in tremendous frustration.

POM. One thing that we noticed on coming here and that has been written up about and that seemed to be the increased permanence of COSATU as a member of the alliance. It appeared to be moving centre stage. It was Jay Naidoo who made the announcement of possible mass action as far back, I think, as last March and gave the government some timetable to meet and when everyone turned on the television from the beginning of July up to this day it was Jay Naidoo, Jay Naidoo. Has COSATU become, because of its organisational skills and it's negotiating skills, is it beginning to assume a more prominent, I won't say pre-eminent, but more prominent place in the alliance?

MM. I think COSATU has always occupied a prominent position in the liberation struggle since it was formed in 1985 and I think what one saw with that prominence, it's not always difficult for observers and analysts to observe the peaks of the different components of the alliance itself. Now for me it doesn't surprise me. I think I see it as an inevitable consequence of the way in which the alliance is structured and the relative strengths in terms of the positions they occupy within the broad spectrum of SA society and that when we are talking about a general strike, for example, I don't think it's out of place for Jay Naidoo to be the one who is prominent at that point in time because it is that part of the national constituency which directly falls under his command, that is going to be the one that will be called upon to optimise the effects of the action more than perhaps any other sector. So in that sense it is a profile which I think is commensurate with the contribution and the impact of the constituency that it represents.

POM. We were in Namibia a while ago and we were talking to some government people there. They said they were experiencing a problem with the trade unions, that the unions were really coming and saying you've been two years in power, nothing has changed, we were a part of it, we claim ownership in the struggle, we want inequities that exist to be redressed and redressed now, and the government are saying that we don't have the resources, we simply can't do it. There were the beginnings of an antagonistic relationship that would be based on labour not seeing itself as a special interest but as some other body that had ownership in the struggle here. When you look at the future here, even interim or post period, and you see on the one hand the need for massive redistribution of wealth and on the other hand a need to get higher productivity. In the short run at least it can be a clash between the two. Do you see labour moving its own way in a post-transitional phase or with labour being able to hold its constituency that they can maybe alleviate some of the demands of its constituent groups?

MM. Well I can only hope that they will be able to do that. As to whether they will, they can, and whether they will do that I think it's a moot point at the moment and it's something that one can ascertain by evaluating exactly what kinds of forces that are at play within the labour movement itself and in the broad political spectrum itself and this by no means is a new discussion on this question of the permanence of labour, it was there enough in the eighties at the time of the state of emergency, the time of the UDF and it's been an ongoing debate from the time when the issue was between charterism and workerism. It's an issue which actually is located within those ongoing debates and it's more going to be a case of how a workable balance can be found because if you don't have a balance between those various strains in society you will either have the process still taking one direction or the other direction and in this particular case there will still be elements within the union movement who will continue to want to push for options that may have been proven not to be viable. They will still be there so it's only a case of what those rational, level-headed leadership or members of the union movement are able to do to countervail and present the union movement as a much more balanced and rational entity. So it's an ongoing tension and struggle.

POM. As you've watched what began as a tentative dialogue between the government and the ANC and the movement towards more formal negotiations, what evolution in government policy have you seen that you regard as being significant and what evolution have you seen in ANC policy that you would regard as being significant? Who's doing the most moving if they're both here to start with, if the ANC is coming like this and the government is coming like that?

MM. If I consider the fact that not so long ago the ANC was not allowed to operate in the country, if one considers the fact that most of the ANC leadership were either in detention or in jail and the government in fact had not even conceived on the notion of negotiating with the ANC, even up to five years ago one could argue, and the fact that we are today looking at a government which is beginning to make sounds and to actually utilise statements even on the question of a constitution making body, actually I can see the ANC as being the one that has done the most of the moving in this case. It has done a substantial amount of moving to want to accommodate the fact that rather than actually shooting its way to Pretoria let us actually save our country and take the negotiation route and I think that for any movement that point represents a major, I would say, a major compromise, a major change or adjustment of its policies because it literally meant that the ANC's armed commanders and staff had to actually come back right inside the country and be within the niche of this animal that they have been fighting all these years with the ever present risk that they can get all consumed. But they are still there and using the other skills available to them to negotiate their way through and in that sense in fact getting the government to the kinds of positions which in fact five, ten years ago would have been unthinkable.

. Now I'm saying so not so much as a way of giving credit to the government but more as a recognition of what it has taken to get us to this particular point that we are at. I know the government uses the case of moving themselves relative to the ANC as a way of scoring political mileage over the fact that we are the good boys of this thing, look how nice we have been, look how we have changed, etc. But they are skilled politicians, they are able to use those things to gain an extra mile out of it but the fact of the matter is that they are the ones who have been in retreat and one can only see the democratic forces being on the advance.

POM. The second question that has arisen is, did anyone want the collapse of CODESA? Did the government want the process to deadlock and become indefinitely extended? Did it want it to collapse? Did the ANC find, a number of people have said to us that the ANC found that it was entering agreements which were very restrictive, they had accepted the principle that an interim constitution would be drawn up by CODESA and that interim constitution would contain provisions providing for entrenched rights of the regions to be defined by CODESA and to be entrenched in the constitution, that they had accepted that the boundaries of the regions should be drawn up by CODESA and not by an elected body, and that they had to find a way out, that the Constituent Assembly would only really be amending a constitution that would require a 70% margin and not really drawing a new constitution up? I find it hard myself to reconcile on the one hand saying we want a constitution to be drawn up by a Constituent Assembly and on the other hand to look at the kinds of agreements that had been entered into prior to the collapse of CODESA and to find that the two synchronise, they don't seem to synchronise with each other.

MM. Well I mean I actually saw the CODESA agreements, especially those that would have to do with the functioning of an elected constitution making body as mainly the agreements which basically denote and lay the broad parameters within which that forum would actually proceed and the fact of an interim constitution coming out of CODESA, some would argue that they did not see that as inconsistent with the need for the final constitution to be drawn up by an elected constitution making body. The main objection that the ANC was showing was pointing out that that was in fact the way the NP and government were actually seen in trying to put such conditions or agreements even at the level of CODESA 2 which would have the net effect of making the interim constitution. It would actually open the way for the possibility of the interim constitution becoming either semi-permanent or even permanent because once it becomes semi-permanent if one would look at about five to ten years you don't know what else may happen in that period and in the end that's actually been settled with that so-called interim constitution. So a degree of uncertainty with the approach of the NP was greater insofar as the life of this interim constitution was concerned than what the ANC and its allies would have liked to be the case.

POM. It seems to me though that the ANC had conceded on issues on which it's now reversed itself. That is on the devolution of powers and in CODESA they had agreed that the powers of the regions would be defined by CODESA and written into an interim constitution and that the residual powers would be reserved for the central government at the policy conference. The ANC directly contradicted that thing, powers must be devolved by parliament to the regions. The ANC had agreed that the boundaries of the regions would be addressed in CODESA, not in parliament and, again, the policy conference came out and said, no, it must be a Constituent Assembly that draws up, defines the regions. Do you know what I'm saying? Am I reading it correctly or am I getting it wrong, that's what I'm really asking?

MM. I'm not a constitutional expert myself so I would not even pretend to have 100% comprehension of how one goes about actually handling those except that the general principles which one looks at for guidance is one that says it is important that you - the notion of regional, of some power at the regional level, that's accepted. Even the ANC has come round to accept that because if one looks even at successful government all over the world you will find a degree of regional or local authorities and if one could even argue that that is not even inconsistent even with the ANC's own mass approach. But the chief thing here relates to how and what actually devolves to the regions.

. Now given the overwhelming national task that is going to emerge, what powers do you leave in place for central government to be able to execute national programmes? There's a lot of tension between those areas and even within the ANC I am not convinced that, I am sure that even in the ANC there isn't unanimity even on that question. I know that for a fact that the debate is still going on. Even the policy conference may come out with a document, etc., but I think that some people have actually found those to be still wanting in certain important respects especially relating to questions of power and what are those issues? Can you define them today or is it something that you wait for the broad constitution to be in place, for the constitution making body to tell them exactly what the respective functions of the regional and local administrations are going to be relative to the national decision making process. So in a sense personally I am still actually trying for clarity although one accepts that we're not going to be able to afford the regional issues.

. I think what we could fight for is that regional government does not translate into ethnic government or ethnic domination, etc., but structure it in such a way that it relates to the actual specific needs that the country is faced with from the point of view of development and also to take into account specific economic structures in SA as it presently stands because you can have a regional government in the middle of the Karoo with nothing else but 10,000 sheep to look after and you will have another region called the PWV region with all the wealth, etc., and how you actually structure the relationships between those becomes very critical. People are still looking for solutions. I don't think I have answers to that myself.

POM. Do you see the week of the mass action - was mass action necessary in order to pull the grassroots back into the ANC, quell the doubts of the doubting Thomases, once again give coherence to the ANC and the movement that had its wellsprings in people? That's one. Two, was it successful in a political sense, in the sense that it sent a message to the government of such proportions that it would impel the government to respond by being more accommodative and by making it get on with the process in a more efficacious and quicker way?

MM. I don't know, it's not yet clear how the government will eventually respond to its realisation or its observation of the effect of mass action but I think that one of the main things that comes out of mass action is the ability, the capacity of organisations like the ANC and COSATU to mobilise their members when they want to. It could be argued whether did this particular mobilisation justify the cost in terms of what it has cost SA and what it has cost the various members, etc., does it justify the end itself? My argument is that mass action is something that should have been there even from the beginning of CODESA so for me it's not a case of whether this particular mass action is justified or not. For me mass action within a democratic environment is something that must always be a specific feature of democratic expression for people.

. Now, of course, I mean I distinguish between legitimate protest actions of people on an ongoing basis and violent activities which actually could undermine the entire process and the country's wealth. What I am just basically alluding to is just mass action as a function of people's desire to find expression through their demands, their frustrations, etc., and I think the ANC as an organisation has a responsibility in giving people that forum, that avenue for them to give expression, to vent their own feelings in that way. So I actually think, therefore, that as the ANC flexing its muscles through mass action, I think it was successful. Whether it's final success by way of the government responding to the ANC's demands on the basis that mass action was powerful or not, I think that's something that's still down the line.

POM. You were just finishing up, talking about mass action.

MM. I always believe that mass action is a necessary aspect of struggle and I think that it adds a quality to democracy that I think this country hasn't experienced under the NP, or even many other countries for that matter haven't experienced it and I think that the ANC was much more, I would say, astute in taking the opportunity at that point in time to rekindle interest in the process and to actually get people much more seized with what the issues facing the country are because some of the issues that were placed before the people and that the people raised their banners with during those protest marches are the questions of the Constituent Assembly and an interim government which are basically the issues that the ANC and the government have to deal with now in terms of determining how they are going to co-operate in negotiations. Is it back to CODESA or is it back to interim government? And I think what mass action has actually clearly done is to place interim government quite high on the agenda of negotiations at the moment.

POM. The first year we came here people talked a lot about the youth, the lost generation.

MM. You see one of them is going grey now!

POM. They're unemployed, unemployable, they have this culture of militancy. Two years have gone on and there haven't been any real changes in the lives of people on the ground. You have Chris Hani talking about local defence units in areas that have gotten out of control. Besides the political violence you have a more generalised culture of violence where people now use political posture as a reason for committing crime. Is there any danger of that kind of violence becoming so endemic to communities that it virtually is like a fire out of control, just burns on with a certain intensity, not a huge intensity but with a certain consistent intensity year after year but that it cannot be controlled?

MM. I think that's a legitimate fear and this is what I also fear the most and I think that you must know that some of the things that some people have been beginning to see now or be aware of today I saw for the first time 16 years ago.

POM. Things like?

MM. In Soweto, that's about 16 years ago, and those things, some people have been involved in similar things from that period onwards which is a tragedy of SA. It's not even a question now of whether will we be able to deal with the consequences of this ongoing cycle, we're already beginning to experience the consequences because there are children who come from communities where since 16 years ago there has not been peace, all they have grown up knowing is that in fact people shoot each other to kill because if you need to survive you have to act in a particular way. Even in Soweto for that matter, in spite of the relative levels of violence and calm that the area has seen but there is a culture that becomes endemic and I think that if one looks at the school situation, which is one of the more tragic areas that we are looking at here, it's so very easy to look at the teachers and to accuse the teachers and the students, but what about the officials in the education departments who are behaving today in 1992 the same way in which they behaved to similar problems 16 years ago?

. Now there comes a point where it doesn't really matter whether who's the cause and what is the effect, the problem now is the entire situation and how to get it resolved is the major challenge that we are facing. My own personal feeling on this matter is one of - I mean sometimes you get a feeling of hopelessness, you feel, well, thank God this is another day I'm still alive, I've survived, etc. You open the newspaper and there's yet another person you know who's been killed so this thing goes on and on. I'm not a sociologist but I don't think it defies a simple mind to see in fact what the consequences of the situation where this violence does not abate because if one looks at the hostel situation which is one of the areas where much of this violence has been coming from - I was thinking the other morning that in 1976 we had a problem with hostel dwellers. I remember us actually going into some of the hostels like Dube looking for the Indunas in those hostels and actually negotiating with them and talking with them and we were able to resolve that thing. I ask myself why was it, we had the problem of Dube Hostel in 1976 and subsequently with the other hostels we were able to intervene but today we can't do that. Now trying to look for the answers it can only be that the thing has become politicised because then the grievances made in general that those people had and when they were addressed genuinely by us going to them under cover of darkness into those hostels, talking to those there and they were able to appreciate our position and we resolved the matter. But now there are much more, greater agendas, political agendas, etc., which actually also in a way perpetuate the cycle.

POM. I want you to relate that to in terms of whether Buthelezi has the capacity to be a spoiler in this whole thing. He sits up there in Ulundi, bitter, militant, making noises about what he will do if the Zulu King and the Zulu nation are not made a part of any agreement that comes out of CODESA or any other negotiated forum. Does he have the wherewithal to thwart an agreement made between the principal parties, the ANC alliance and the government and to bring about a situation of chronic low-level civil war in Natal?

MM. I don't think it's even that, I think the question could get one to hypothesise, but there is a reality in Natal where because things were not going precisely according to the way in which he wanted them to go and every now and then one reads statements from him that say that unless this or that happens this violence will never stop. Now one is not sure how much of that is a Freudian slip, basically the subconscious revealing itself in that kind of way to what basically is at the back of his mind even though he puts it across as a possibility but being at the same time something that you actually are involved in, actually doing. Now that has been one of his consistent tunes about the possibility of the violence escalating if A, B or C doesn't happen.

. Now I have, from the UDF, from our times in the UDF, the conflict in Natal hasn't changed in terms of its nature, it has only increased in scope and extent and perhaps even viciousness and now whether that can be reversed I am increasingly doubtful. This past week, two days ago one was looking at what has been happening in the world markets and with the fact that the SA rand, the way in which it performed in spite of interventions from Central Bank etc., I was trying to find out what message is that and suddenly you begin to hear talk of possible devaluation as an option that we could go. And you can actually see yourself slowly moving into that bracket which basically would actually locate you within those basket cases of the world where your economy would just be as useless as the many others that can't exchange for anything in the world markets. I think that's one of the real dangers that we have and if this increases for the next two years I think the path backwards, I think it's much easier to go backwards than to go forwards sometimes especially when it comes to human civilisation and development.

POM. Some people say, well the way you take care of Buthelezi is the government pulls the rug out from under him, simply says no money, buddy you're on your own. My question is, can you draw on conservative Zulu nationalism or ethnic stirrings or rural Zulus to enable him to carry out - I mean it only takes the IRA 300 people to destablilise all of Northern Ireland so that would mean about 50 operatives to destabilise a community of a million and a half people. You don't have to have a lot of people, you just have to have access to guns.

MM. My argument is that in a situation where you're all playing honest politics, yourself is there for people to see, and my conclusion is that Dr Buthelezi must have the support but I think at the moment, every day I sit here there's hundreds of people marching to this hostel and to that hostel, etc., and the fact of the matter is that there are people who support him. They are there, they are not ten, they are not twenty. He calls meetings and people go, whatever the reason. The point is that it can be argued as to why those people go there. That's the intellectual discourse you can get into some point as to why they go there. Is it because of peer pressure? Is it because they are afraid? You know various reasons but those people do go there and it is those same people who can get mobilised and they may have gone there for the wrong reasons, for less than honourable reasons. But after a number of events where they get involved in executing missions, death squads or whatever, they eventually become part of that kind of psychology, part of that group and they act, it's no longer - at that level it's inconsequential whether the person went there willingly or unwillingly, etc. In the long term perhaps yes, but at that point it doesn't really matter.

PAT. Do you think that with that violence and that kind of culture you can, practically speaking, have elections in that part of the country, so that is part of the democratic culture?

MM. The question of an election is also an intriguing one in this environment. I was arguing with Valli yesterday, well not really arguing but having a chat about what the options are here, and basically saying the point of the matter is that there was a time when it was the government which was saying it's not going to negotiate unless the ANC stops violence. Come Boipatong the question has changed, it's the ANC now saying unless you stop the violence we're not going to talk. Now I don't personally think those are statements cast in iron. I think people will work around that as opportunities arise. But the problem with that kind of argument, violence is a problem. It's difficult to say you can have elections where the violence is at such levels that it's just mayhem all over. Say, for example, in Sarajevo, you can't have an election there in Sarajevo today but we have violence of a different sort which I think it could be that calling for an election may well be just what helps the situation rather than exacerbates it. But then that is going to require more than just the calling of the election, that is going to require a situation where the various parties can actually agree on the ground rules, etc., and there is already a foreign presence that has been accepted at a certain level. At that point then it will not be difficult for their presence to play a different role around the process of elections so you already can see in fact certain things begin to get into place but I think that it will be allowing the process to be held to ransom even by mavericks, by hit squads and by those kinds of loose canons who were abandoned down there but the fact of the matter is that some people who can use the argument of saying we can't talk for as long as there is violence, but when is violence going to end? Can you say that today there is no more violence in our country, thank God, now let's go and have a happy election? If you actually use an election as a struggle, as a weapon against the violence, it purely depends on how the organisations themselves choose to utilise that.

POM. About the ANC's insistence which you've had, held unwaveringly for two years, that the government is behind the violence, is de Klerk in your view, or the ANC's view (I don't know how this is discussed), in full control of his security apparatus, i.e. did he know enough about certain structures and how they operate to get a handle on that? But more importantly can he take decisive action, fire a General here, fire a General there, hold Police Commanders responsible for actions that the police forces carry out, instigate a special board of enquiry himself, or will he risk alienating key elements in his security forces or the ordinary membership, that he can't rely on it, that they become part of the problem in a different way, that the only thing that stands between you and him is his security forces, that's his ultimate source of power?

MM. I'm more inclined to look at it in terms of the latter part because I think that would be - I've always said that the thing here is that we are talking about political power and we are talking about privilege, that nowhere in history, maybe Jesus and his disciples were the exceptions, nowhere in history I think have people in those kind of positions given in unless there is divine intervention and they all turn into Mormons and what have you, the religious type, and become part of the family. It may sound like a cliché but I think my own experience, and even here in SA for that matter, one actually sees a de Klerk here who understands very well the fact that his game is to actually manoeuvre things in such a way that at a critical moment his party is the party that leads beyond D-Day, that leads beyond D-Day, and that is my own assessment of the thinking of de Klerk and of his Ministers.

. I was listening to Adriaan Vlok or Hernus Kriel on Radio 702, he was phoning from his car phone, there was some programme on yesterday, I think it was about the police, the fact that the police were going to be invited to observe the IFP training camp, etc., and he was basically making the statement that, look as far as we are concerned the NP is the only party that could lead SA to democracy. I would like to believe they're just making political statements loosely but my biggest fear is that they actually believe that and if they believe that it means that for them to achieve that they have to continue doing certain things they have been doing in the past, one of them being destabilisation.

. It may not be Mozambique today but it definitely continues still to the ANC and anyone else still associated with supporting the ANC. If they can destabilise the ANC's power base they will do it. But then what is the most efficient way, assuming you're the NP, that you think you can destabilise the ANC? Is it by sending your MPs to go and debate with the Mohammed Valli Moosas or with the Cyril Ramaphosas in Soweto? No, you will never win the day there. I think that is pretty obvious, so there are some of the more conventional ways in which people empower, would actually act with a view towards preserving their power or putting themselves in an advantageous position over their own enemies, the military, the police.

. Now does de Klerk have control? I would like to believe he does but there is no willingness on his part yet. You can see problem after problem that has arisen, he throws a commission at those problems that arise where a lot of these guys will be implicated and he has not acted upon them. Those Generals whose names have appeared in the murders, etc., now then it can be said that perhaps they have become such a power that he himself is powerless to act against them. It may be true, may be true, but then doesn't that call upon him if the interest of SA, what it's about, was to look at his position and the situation differently and say who - evaluate the situation and say, who in this country will support me if I take action against these people? If I take action who will support me? I am sure the ANC can support him, the world will support him, etc., but the question is does he really want to do it but that's hard to tell without being a fly on the wall.

POM. This is a related question and it regards amnesty. One argument we've heard a few times is that if there isn't some kind of blanket amnesty that any new government will never get political control of the security forces and that in the absence of any kind of amnesty you're encouraging those elements in the military who know they are guilty of crimes to pursue policies to destabilise whenever a new government comes into being. Where would you stand on the question of amnesty?

MM. Amnesty is a generally accepted international principle, especially at the point where conflicts are resolved. I don't think one would disagree with that. The key question as far as amnesty is concerned in this country is who declares the amnesty. Do you get involved in killing people and thereafter you declare an amnesty?

POM. Give amnesty to yourself?

MM. To yourself as well. There is an inconsistency there. I don't know how it gets resolved and I would be on the side of things that would say that should rather be a role and the job of an interim government. In my view it could be, it may be a very important thing that the interim government would be the one that does that from the point of view of first credibility and also from the point of view of taking care of some of those concerns that people are expressing in terms of actually not stoking up fires of third or fourth columns and stuff like that and where it is the government which is leading to transition, at least those elements would see that actually there is something, what we feared is not going to happen and we are secured, etc. It does help in bringing down in fact those kinds of possible scenarios and my view would be that an interim government should be charged amongst other things with that key question of the amnesty rather than it just being something that is done by the NP.

POM. OK. Thank you ever so much for the time. Hope you're feeling better.