This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

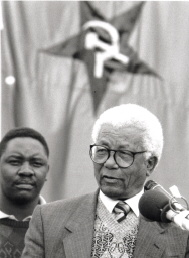

06 Oct 1995: Sisulu, Walter

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Maybe we could start with just your reflections on how far the country has come up to the eve of the local elections.

WS. That short period has now moved as fast as was expected, but the difficulties have to be appreciated of any transitional period. It's the most difficult period. Sometimes I feel that we have not done sufficient to educate people to understand that we have reached a new period, it's a new struggle. The greater emphasis now is on advancing our economy, secondly the building of a nation. Building of a nation in a country like South Africa which has been torn into bits by racialism is one of the most difficult things to do. Just a remark by a white comrade, it's easy to misinterpret just because he is white, something which you would not have resented if it was said by an African but because he's white you say, well he thinks they are better, you are thinking of the past. It's a most difficult thing to do. Now we also should have tried to educate the masses of the people to appreciate the great cycle because I call it a great revolution. It's a struggle that has gone on not for decades but for centuries in different forms and people should have been made to appreciate that the achievement therefore was great. We have achieved that revolution without much violence. We have used violence, entered the war period, but we have been able to sink our differences and negotiate our peaceful settlement. That, again, is not complete and can't be complete in a matter of months. You can't judge anything in the last year or so that can't be justified criticism of anything that is done. Give the people time, look at the direction of things, then you will see we have a great struggle because our struggle, precisely because it has been a racial struggle, attracted so much attention throughout the corners of the world and when we have achieved the stage we have achieved we are looked upon as people who may inspire a new struggle and on a higher plane. I think I should leave things for your questions.

POM. So are you pleased with the direction in which the country is moving?

WS. I think we are doing comparatively well in the light of what I have already said, in the light of the difficulties we have experienced I think we are doing very well. I think the President has done exceptionally well. He is a most hard working man and in demand everywhere, not only here but in other parts of the world, and I think he has done very well. I don't know where he gets the energy but I think he has got terrific energy and I think that his central point is building the nation, uniting the people of South Africa and I think he is doing very well in that regard.

POM. He said on the occasion of an interview he gave on the 500th day of his presidency, he said a couple of things that struck me as very interesting. He said he blamed the media for the impression that most of his attention was given to whites, saying white editors and owners glossed over his work for the majority and focused on gestures towards conservative whites. He said one must take into account that the media is controlled by whites and the element of racism is still there. Why do you think the white media do this?

WS. They are not quite conscious in some cases of what they are doing. It's the legacy of the past. They look at things in a different way. I myself think the media must be criticised. They are not being constructive in their approach. Perhaps their enthusiasm for democracy carries them too far. They don't look at the situation objectively and try to present a picture that will make a contribution in the building of the country.

POM. So do you think they have been too critical of the government and in particular of the ANC over the last 18 months?

WS. Yes, too critical, without appreciating and understanding the problems that face us. Now I think that the media could do much better than they are doing. Let me give just one example of when an article is written by an African, the approach is different, he tries to understand the situation whereas when it is a white comrade, by and large, I don't know, I'm not trying to generalise because there are very many good white comrades, but the core in the media is misunderstanding the situation and they judge as if nothing has happened. If they were to look at the situation and look where we come from, look at the problems, they would know that they are expected to be constructive in building this very difficult nation.

POM. What would you point to as some of the major achievements of the government in the last 18 months that have been ignored by the media, or insufficient attention has been paid to them?

WS. Well you take for instance on the question of education, it is something which should be emphasised; one of the key questions in all colonial countries is the attention they pay to distort education because if you get education you get people enlightened. Apartheid was even worse. I don't have to explain what the conception of education was as far as the apartheid regime was concerned. They did not hide that. Their main interest is to use education to distort the whole picture, the whole requirements of humanity. They are not concerned with that, they are concerned with the question - are they achieving their objective? Their objective is to suppress a black man. I don't have to quote Verwoerd but go and look at him, look at things that were done. Look at the whole philosophy of their education. Now I have said already colonial countries, governments, have done this in the past but it was even worse in the case of the apartheid regime. I say, therefore, any achievement, any effort on that field of education should be appreciated, should be understood as it is. The feeding scheme, I know there are weaknesses in it, but it is something, it's an effort. The question of elderly people, the treatment in the hospital, those are matters which must receive attention because there are difficulties. We are doing that work in spite of the problems. I don't want to talk about the question of housing because we are still very much behind there, any criticism there is understandable.

POM. Do you think that South Africa is held to a different yardstick, that it's judged in a different way than other African countries, that more is expected?

WS. Perhaps there is also that, that to say that because of the perception of Africa as a whole our situation is judged wrongly. Already you are looking at the failures of the entire Africa and everything that we do you already misjudge it because you base yourself on that situation. We are quite different. We have been different even in our struggle. We have achieved greatness in the struggle. The very fact that we could have decided not to depend entirely on the question of violence, the fact that we are not bitter; you take any of the leaders of the African National Congress, no bitterness. Why? Any reasonable person is going to ask that question. Why not bitterness? It's because of the philosophy of life, the way we have educated ourselves, the way we have conducted our education. It was not to be fighting the white man, it was the system, in order to introduce a system. So there is no bitterness. That alone should teach people how different we are in our struggle.

POM. Do you think that, again, turning to the media, that the media often over-criticise the government and the ANC because they want to show that black people can't do things the right way?

WS. That's right, that's correct. We told you so, look at what it is. I remember at one time I went to Cape Town and whilst I was there an African occupied some premises or buildings which were occupied by coloureds, the Nationalist Party said, We told you already that's what is happening. We were in the meantime taking action against those people who were occupying because we were aware of dangers inherent in that situation.

POM. And does the same apply to this, what I find, this constant reference to the gravy train?

WS. Yes. Well in the gravy train we are also responsible within the leadership itself. They emphasise the wrong thing, the gravy train, without examining it properly. The fact of that is to create a division between the parliamentarians and non-parliamentarians without appreciating and examining the difficulties. I am not sure whether I heard this quite correctly. I listened to a talk one day, one of the whips of the Nationalist Party, I may be mis-quoting, he says, I have been in parliament for 17 years, I have never seen what I see today. And he says, The manner in which they are carrying on, they are working hard these people, he is saying so despite the criticism and he is examining the situation from the knowledge he knows. He says, They are not, I forget the term now, what he was trying to say is that there is nothing they do merely to show that we do something without examining it properly. I thought I appreciated that talk. It was in parliament. I thought because it comes from opposition, he is appreciating. Now I am trying to say our own people have made a mistake in emphasising the question of the gravy train, it's not only the enemy but within the movement itself. I don't think they understood it clearly. Perhaps they went too fast in coming to a judgement. It's something which required a proper analysis and a proper understanding of the other people.

POM. If I'm hearing you correctly, you would be saying that this criticism of this thing called the gravy train is not justified.

WS. It's over-emphasised.

POM. Over-emphasised and by many people within your own movement and that creates divisions between the parliamentarians and the average man on the street.

WS. That's correct, and I say I am rather sorry about that type of thing. I have emphasised that in my sometimes speaking, but sometimes I criticise myself by speaking too late on an issue like that. I'm not in parliament but I understand the situation. I have examined the position there and I thought that these people are working very hard. I have no doubt there are quite a lot of mistakes and particularly the recent absence, I accept that criticism. It was unfortunate that type of thing should happen, but I have been trying to follow the trends and I thought that the parliamentarians do work very hard. Exceptions will always be there.

POM. Let me turn to KwaZulu Natal which worries me a lot. Every year I come back I think I ask you about KwaZulu/Natal and I ask everybody about KwaZulu/Natal. I seems to me that once again the violence is slowly getting out of hand or is out of hand, that Chief Buthelezi is playing brinkmanship politics, that he is now not talking about federation, he's talking about autonomy and the right of the Zulu people to self-determination. Do you think this problem is being dealt with seriously enough within government or are they saying, well that's Gatsha and he's just playing his usual brinkmanship and in the end he'll come round?

WS. To correctly characterise brinkmanship, once you play politics of that nature you make people not to focus their attention to the right things. It's a serious problem but remember that Natal has always been a bit problematic, even in the ordinary situation there have been problems. They have been exaggerated by the existence of the Bantustans and the contradictions in Buthelezi's approach. I say contradiction, Buthelezi boasts of having rejected independence. He does so in order to prove that he is not for independence, but his actions clearly indicate preparations for breaking within the union. So it is something that worries everybody. The answer to your question, I say the difficulty is that when Buthelezi plays that game he already creates difficulties in handling the situation. The desire of the people of South Africa is to leave South Africa intact as one. Buthelezi he pays lip service to that because his actions indicate an emphasis on Zuluism, Zulu nationalism. It's permissible to have Zulu nationalism but it must be within ...

POM. Within the state of South Africa, the sovereign state of South Africa?

WS. Yes.

POM. So in your mind do you think he is making preparations to play the card of secession or to move closer to it?

WS. Very much closer to it. He is creating in the minds of the people that the answer is one of secession. No answer is going to solve this problem. He has created that in the minds of his own followers and there is nothing to justify that he is in fact moving with the rest of the country.

POM. Do you know him personally?

WS. Yes, oh yes.

POM. I must tell you I have interviewed him every year since 1990 and that he is the only person who replies to me in his own handwriting every year. He says how busy he is and how this and how that and how the other, but he's given me a date on which he will see me and then I will meet him and his humour can go from being absolutely charming to being absolutely surly and everything in between, and sometimes he will answer a question and sometimes he will sit there and say, Professor O'Malley I do not speculate. Professor O'Malley I do not deal in perceptions. Professor O'Malley I do not doodle. and it's impossible to get a reply out of him. How do you read him as an individual?

WS. Well I met him as a young student, militant, well spoken and dedicated to the movement. He says in his biography, I think, that the people who made him to take Chieftaincy were Luthuli and myself. That is true. We regarded him as a bright man who is an educated Chief, who would lead the country and Natal at least, it was the right direction. But he gave an impression, if I read that biography well, as if to say we advocated, we rather influenced him to take Bantustan. We were not concerned with Bantustan, we were concerned with the leadership at the time. The point I am making, he was a soft spoken, well disposed to the whole leadership of the movement. I am absolutely surprised and shocked or perhaps true character is revealed in this way. He is full of contradictions and bitterness which I don't know where it comes from, and ambitions. He has got very, very high ambition. What ambition I don't know because there is no ground for him to think he can lead South Africa. He can cause a lot of trouble within the region, within South Africa, as he is doing today. I don't know then what his aim is. He says he doesn't want independence and he doesn't produce concrete suggestions of what should be done in order to maintain or to meet in harmony. I am unable to understand what exactly he wants.

POM. Have you ever brought these matters up with him and asked him?

WS. No, I must also criticise myself there. I never had a chance of really meeting him and discussing with him. That is a weakness on my part. Whenever I criticise him I criticise him having in mind that I have not played my part in order to see that I influence the trends as far as he is concerned. But right from the beginning his fight appeared to be too sharp, to be very sharp in his dealing with the situation. Arrogant and sharp, destructive in other words. There has been no time when I say I can take an advantage and say, what about this direction, because right from the beginning he is a fighting man and I don't know exactly what he is driving to.

POM. He, I was told, because I've talked to Albertina Luthuli, and I know his granddaughter Nomsa Ngakane very well, and they used to tell me that Buthelezi was kind of a protégé of Chief Luthuli. Would he have been kind of a protégé of yourself, you both saw great potential in him?

WS. Yes I think so, I think he was. As I said I've already quoted what he himself has said in his book. Luthuli looked to a fine young Chief who had a great part to play in the liberation movement. Luthuli was very fond of Mangosuthu Buthelezi. I, myself, was fond of him. He has disappointed all his admirers, disappointed all of them. I don't think there is a single one and I am just surprised with people who still follow him with so destructive a policy. We have fought for decades, for centuries, to bring about a united South Africa, a liberated black population, to bring about a non-racial society. There we are busy being stampeded by being faced with a question of the impossible situation of Buthelezi. I don't know how to describe his situation. I know Nelson was very fond of Buthelezi. He was in fact a lawyer for Buthelezi and the Royal House. He has had a very good relationship with them. If you look at the last letter Nelson wrote just before he came out of jail you will realise that here is a man who was a great admirer of Buthelezi, who is also a great admirer of the royalty of Natal.

POM. Where would I find a copy of that letter? Is it in the President's autobiography?

WS. I think you should look for it, I think it should be somewhere because even Buthelezi was proudly boasting about that. Today perhaps he would be reluctant to give you, but he was boasting about it. The point I am making, here was a great admirer of Buthelezi, here was a man who has got a royal background, who admired the Royal House of Natal for the struggle they have put up. What he wanted, therefore, was that there must be a man who will lead the people of Natal along the right direction. So everybody's, the point I am making, is absolutely disgusted and disappointed.

POM. Does he have any friends?

WS. Well how can these people be friends, those who are supporting him? I don't want to mention names but is it conceivable that they are really supporting Buthelezi? Can they support that policy which he is professing?

POM. But there are already splits within, deep splits within the party.

WS. There should have been something a little more than that because it's an impossible situation to imagine that intelligent men who have themselves struggled could support a policy like that, unless they wanted to destroy a man, they want to destroy him. I don't understand.

POM. But as long as that situation remains as it is in Natal, continually volatile, moving from one crisis to the next, you are never going to get significant foreign investment coming into this country.

WS. That I appreciate very much. I appreciate that very much, that we have that problem. He is probably very much aware of that situation too.

POM. If I were a foreign businessman sitting here with you and I said, Mr Sisulu, I am looking at your country as a place of potential investment and yet I see this festering sore up in KwaZulu/Natal that could explode into countrywide violence or civil war or whatever, why shouldn't I wait and see what happens before I invest?

WS. No, I appreciate that very much, but I say that I don't myself think that the country as a whole is full of violence. It's a particular section and even that, we finally must overcome it. But in the meantime I understand your point very well. In the meantime an investor will say, Let me see what direction things are taking.

POM. Do you think the country is ready for the local government elections? Honestly? I'm publishing nothing until the year 2000.

WS. You see again here one must look at the history of the country and particularly the local government. They have been used, the people have been disgusted with the local government and to educate them to say that it's your asset, it's your future and it's your country, it becomes very difficult. But I think we have done a great deal. Take the question of the elections, just to get an example the general election of 27 April, I have never seen a thing like that which I witnessed during that period.

POM. Neither have I.

WS. I have never seen a thing like that. It has given me wonderful insight into the behaviour of human beings. People were talking about civil war, talking about violence in every corner, but on the day of the election the masses of the people in South Africa took a completely different direction, they said we want to go to the polls. They were prepared to wait from five o'clock to ten o'clock in the evening in order that they should be able to vote. Now that miracle was there, that miracle indicates the desire of the people of South Africa for unity, for great achievement. And I think given the question of - despite the difficulties of local elections, we will go through.

POM. But the system of voting, I ask senior people, government ministers, senior departmental officials, to explain to me the system of voting and no two people give me the same interpretation of how the system will work, and if they don't know how it's supposed to work how are the masses of the people supposed to know when they walk into the polling booth?

WS. There will be those shortcomings but generally people know they are supposed to vote. We vote for Joseph, he is in this ward. We don't vote for John though he is in this ward because of his - the people will be concerned with voting for the right man. They know they need local authorities. They know they can't live in the past which destroyed them. I think the people will vote, will vote correctly too. I think so.

POM. What if, this is my always 'what if' question, and this is a question Dr Buthelezi would never answer, he says, I never answer what if questions, I don't speculate, if it's not in front of me it doesn't exist. But what if, as some people say, that maybe hundreds of thousands of voters turn up to vote who are unregistered either because they didn't know they had to register or they don't appear in the book and they did register, you could have hundreds of people saying I want to vote, what are you going to do with them?

WS. There is that danger because at that stage you can't do anything with them. You will have to rely on those who have been able to understand the situation. You can't do otherwise. That exists, that possibility.

POM. But you can't turn them away can you?

WS. Well, you have got to be guided by the rolls.

POM. Yes I know, but it's very complicated.

WS. The rolls indicate he is not a registered voter. What do you do with that? He just has to be turned away. There is no other way.

POM. One other way that has been suggested, because I know there have been a number of - I keep in touch with the people in the Electoral Commission, is that you would allow them to vote but that you would put their vote in a separate box and you wouldn't count it but you would allow them to actually cast a vote but you would destroy all those votes at the end of the day. Do you think that would be deceptive and that it is better to send the people away?

WS. I think it is really better, let the people be bitter by being sent away. It's a more correct approach.

POM. That they should be sent away?

WS. You can't vote, you have not been able to be registered. I think much has been done in any event to register them but there will be people who are not registered. Those who are not registered it's just a bad job. I don't see how it can be avoided. You want to put the record straight. You want to do what is supposed to be correct and I think that those who have not registered, have not registered, it's unfortunate.

POM. What about the public sector? Would this continuous wave of strikes which have been going on now for a year, whether it's been policemen, whether it's been teachers, whether it's even been bodyguards, and now the latest the nurses' strike which made news all around the world with patients being left to die, is this a matter of ...?

WS. Well I must at once plead guilty. We haven't done what we should have done. To some extent we must take responsibility. After elections it was necessary to inspire people with a direction, a correct direction. We left things because we are too busy. It's a surprising thing, you get a member of the Executive, he goes from one meeting to another, there is no real time for reflecting the situation. This situation, we could have minimised it if we had tackled it right from the beginning. Even now it's not too late to try and correct it and I hope we will be doing so. What happened is that the people took advantage of the situation now, the other side, those who are not our supporters take an advantage of our situation. I hear De Klerk sometimes speaking, they make it worse. He is angry, for instance, for criticising, for Nelson criticising the apartheid of the past. But that is the reality, that is the true solution. How can you be angry? You can say it's unfair to be harping on this issue, but it's the correct thing. It's the situation. They have done so, undermined, they have been undermining any question of proper building of the country. They are not part of that. What I am saying is that it's a grave mistake we have made. We are partly responsible for not educating the people in a correct way. You know it is a difficult thing, this period because people want to be members of the Council and for a little mistake they take an advantage, they want to undermine the process.

POM. So you would see that the National Party is not contributing to rebuilding?

WS. No, I think it is not.

POM. And the IFP isn't contributing to nation building?

WS. I think they are not. I think we are not pulling in the same direction. They are thinking in terms of what is nation building is in the interests of ANC and therefore they can't be party to it. It's a serious mistake and a serious miscalculation, serious misunderstanding of the situation. You can't want to live permanently in destruction. It seems to me, to that extent I say though they are doing these things deliberately but they are not aware of the grave dangers they have created in the country.

POM. I don't know whether you followed the OJ trial at all? I don't know how anyone could escape not following some of it even if you didn't want to follow it, but opinion polls in the States show that about 70% of whites believe he was guilty and that 70% of blacks believe he was not guilty. People's opinion split right along the racial divide. Do you think that is inevitable to happen here for just a long, long time because it is a legacy of apartheid?

WS. No, I don't think it's something that is going to go on indefinitely. There will always be those tendencies. You see our situation, our orientation, our politics have been to build a non-racial society and therefore the extremes of racialism are not going to be easily applicable to our situation.

POM. Does what happened in the United States with that verdict and the way people reacted to it, does that surprise you or not surprise you?

WS. You are asking me whether I followed it. I don't think I did follow it. Actually I was under the impression that OJ killed his wife and the partner and I thought that his plea therefore would be, I was angry. But I find it is completely different. I have not followed it. I have just followed it towards the end. At the beginning I didn't follow it at all.

POM. Like myself. It went on for too long and you would have to sit in front of your television all day. Let me ask you, what's happened to the RDP? It was being touted 18 months ago as being the centrepiece of reconstruction and development yet it seems to have gotten bogged down in bureaucratic procedures. For example, I read yesterday that in KwaZulu/Natal out of 400 million rand allocated by the RDP for projects there something less than 60 million had been spent and you had Jacob Zuma saying, well the money got lost in the cracks in the bureaucratic procedure, processes weren't in place. It's not obviously achieving what it was supposed to achieve. Is there a reason for that, or is that a wrong statement on my part?

WS. No, I just want to explain my own position, you know I'm not an official today.

POM. That's why you're more honest.

WS. I must look at the situation in a realistic way as a man who's a loyal member of the organisation but at the same time accept criticism. I do think that the RDP has not gone as has been expected and I have not been able to find out the real reason and my criticism can stand only if I have studied the situation and I am able to criticise a particular approach on the thing. I have not been able to follow, I have looked like many of our people with great admiration, with enthusiasm everybody accepted RDP, but I think we have failed somehow to keep the momentum. As I say I am not really qualified at this stage to give you the reasons except to say I appreciate that there are failures. Somebody came to me and said that I think RDP is not moving in the right direction and he wanted to have a discussion with the President. I immediately said, I think it's a good idea, I will encourage that. I spoke to the President to say there is this criticism, I would like you to meet this man. I am not sure what finally happened. I am concerned with this. One of the most popular slogans of RDP, and people would say when they see the cleaning of the streets, say RDP, RDP. There was great enthusiasm by ordinary people about the RDP and I think the delay, bureaucracy, has done quite a great deal of harm.

POM. Do you think there are still strong elements of the white civil service that are actively working against the implementation of government programmes?

WS. I have no doubt about that. I think that there is a great deal of that. I don't want to exaggerate it, I never like people exaggerating it because it does harm, but I think there is a great deal of that.

POM. What's the way around that?

WS. No other way except educating the people, because those who do that they do so really with ignorance and bitterness of some kind. What is the answer? The answer is to educate, you just have to educate those people that the direction is one. There is no way you can take this country back to apartheid. Out of the question, it can never happen and, therefore, we must choose between building and taking a straight route and undermining this process.

POM. One of the ways the gravy train was explained to me was in terms of the enormous amounts of money paid to retrench white civil servants, the huge salaries they still draw and more importantly that when the act was passed to protect the jobs of civil servants it didn't just protect the jobs of white civil servants it protected the jobs of civil servants in the independent states and the Bantustans all of whom got huge promotions in the waning days of apartheid and huge salary increases and are absolutely incompetent and they are protected under the law too.

WS. I think there is justification for that analysis. There is a great deal of it. I accept that.

POM. When you look at the constitutional deliberations now taking place, do you see the new constitution that will emerge as being a much stronger and fuller document, in some ways radically different from the interim constitution?

WS. Yes.

POM. Or do you see it as just being a refinement of the interim constitution?

WS. No, I think that there will be radical differences. You see the interim constitution was concerned really more with compromises and in some cases things handled not in so realistic a way. But people are now debating, from what I follow, debating the new constitution. I think the new constitution will be much more positive than the interim constitution.

POM. Listening to you and, again, correct my impression if it's not correct, I get the impression that you are saying that for the last 18 months we have tried to embark upon a programme of nation building, of bringing people together and of reconciliation and our two main partners, so to speak, the IFP and the NP, aren't with us on that course, we don't share common objectives and the time has come to let them know that we will not be stopped in the pursuit of nation building, that the majority will assert itself.

WS. Yes, that's what I say. I say at least with the new constitution the people will be deciding one way or the other. They are no longer prepared for unworkable compromises. They will want a straight route, well straight in the limited sense, and they will try to exact the will of the majority, not that compromises there will be altogether abandoned but they don't become the main concern. The main concern is to say, will this be a lasting constitution? Is this the type of constitution we want? That should be the positive outlook.

POM. I want you, before I finish up, to go back to Robben Island. I haven't sent you on a transcript of your last interview because I had some technical difficulties with it and it wasn't coming across very clear, so I have sent the tape off to an expert to rectify it, but you will be getting a copy. I remember we were having a very good discussion of your memories of Robben Island and your days there. What were the darkest moments in those 27 years that you had when you were on Robben Island?

WS. Well I think the darkest moments were the period of the trial. The darkest moment, not knowing what directions things are going to go.

POM. Five to seven minutes.

WS. Those were the darkest hours. Once that was over we were in a position to think ahead, to think creatively, constructively. That was our situation. We immediately wasted no time to set up machinery when we were in Robben Island, clear as to what the position was likely to be. So the darkest hour was the time of the trial.

POM. Just two last questions and then two things to ask you on a personal level. One thing to tell you on a personal level and one thing to ask you. One is when President Mandela began his process of negotiation with Kobie Coetsee, would he report back to you and let you know what kind of conversations he was having with Mr Coetsee and then with other government officials and would you advise him as to the way forward, or did you leave it up to him to make the decisions as he thought best?

WS. It took a long time before he could have a chance of letting us know but I place confidence in his ability to assess the situation precisely because once we had appointed him as a leader in prison and he was in constant contact with the authorities and his approach was to put forward the policy of the ANC, convince our opposition as to correctness of the policies of the ANC, and because he was going to take that direction I knew that he would not go wrong. He was guided by the policy we have made.

POM. Was that shared by the rest of the leadership?

WS. Well sometimes but not always. You see I had more confidence in him, I had worked with him far more than anyone else and therefore we could not be on a par as far as that is concerned. But I had that confidence.

POM. Just last, now that you're retired, you're not in retirement since you're here every day having more appointments than ever, it's a funny kind of retirement. Thank you very, very much for your time. Every year I appreciate it.